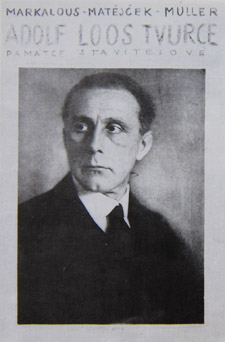

Bohumil Markalous: Adolf Loos creator

A man died who said to Vienna, "No – never!"

|

| Model of the unpublished book by Bohumil Markalous, Antonín Matějíček, and František Müller Adolf Loos creator. Around 1935 |

This characterizes Loos's personality in the preface to the Czech collection of his scattered essays and articles Words into the Void (Library Ars, Orbis), to which I have given the subtitle: This book speaks to the soul, talks about thrift, discusses the miserable rich man, about architecture as a craft, about clothing as a building principle, about the leg, the shoe and walking, about the true style, which is named human need and comfort, about women’s fashion as a sad chapter in cultural history, about plumbers, who are the first craftsmen in the state, and many other things.

Here is succinctly contained the program of Loos's life’s work, his civilizing efforts, which he fundamentally did not change from 1896, thus for thirty-seven years, and which he proclaimed both intellectually and practically with fanatical consistency despite everything. A friend of Karl Kraus, Altenberg, a supporter and patron of Kokoschka and Arnold Schönberg, stubbornly adhered to his principles for almost forty years, convinced of the honesty of his work, which respected simple humanity and its basic needs, which did not want to be anything more than that, and which had in an unlimited, almost divine respect for natural gifts, material, matter, which man of the late nineteenth century, the unthrifty, snobbish creature, devastated against its nature.

From this emphasis on humanity, primary relationships, and needs, permeated by prejudices, lies of pseudo-civilization, flows the significance of Adolf Loos for the development of the idea of democracy.

The first level of construction clothing: human skin

No one expressed Semper's principle of construction as clothing to such a precise degree as Adolf Loos. It begins with human skin and ends with generous urbanism.

The first garment of man is his own skin. Loos devoted much attention to this, and we outlined the brief content of his conclusions in the chapter on plumbers.

Every era is thrifty in its own way. The eighteenth century spent much on food and was very frugal with cleanliness. This century is a smelly century – it can still be felt from the furniture.

Today we take more care of cleanliness!

American soldiers arranged bathrooms in France and in the trenches. And what happened? It was exclaimed: “Are these soldiers?”

Why was this exclaimed? Because the image of a good soldier is inseparably associated with us in Central Europe with an unclean and stinky soldier!

After skin comes linen

We do wear outer clothing like the whole civilized world, thus distinguishing ourselves from peasants, who still wear medieval costumes. However, we do not differ from them in our linen. Woe to us if our surface clothing fell off piece by piece and we were only dressed in linen! Then it would be seen that we are actually wearing European clothes merely out of foolish imitation, because underneath we all still wear national costumes. To play outwardly as a modern person and to deceive with those parts of the outfit that are not visible does not speak well of an honest character.

In Hungary, people, so-called educated classes, wear the same underpants as common folk, and in Vienna, educated men do not essentially wear different linen than lower Austrian peasants. We live at least fifty years behind the times when England won the victory of underwear made from coarse cloth over woven underwear. A hundred years ago, people wrapped themselves entirely in linen. Over the century, the manufacturer of coarse goods gradually conquered one part of the body after another: he started with knitted socks for the foot and gradually took possession of the whole body. Yet in our case, coarse goods only belong to the lower half of the body, while the upper must endure that the knitted shirt is still covered by a linen shirt. But even that is not so far actually. In Austria, we have only remained at the feet. We wear knitted socks and no longer wear legwraps. However, we do wear linen underpants – a dreadful thing that has died out in England and America.

If a man from the Balkan states, who still wears legwraps, came to Vienna and entered a linen shop to buy his usual legwraps, he would receive an incomprehensible refusal, namely, that he could not get legwraps. But for an order, yes.

“My God, what is then worn?”

“Socks.”

“Socks? That is very uncomfortable. And too warm in summer. Does no one wear legwraps anymore?”

And yet, quite elderly people do. Young people consider legwraps to be unaesthetic and uncomfortable. A good man from the Balkan states decides with a heavy heart that he will try socks.

As soon as the Balkan man stops wearing legwraps and begins to wear socks – he rises a notch in human civilization.

And now we transfer the story we just told to New York, where our Viennese comes and wants to buy in a New York shop – linen underpants. It would happen just the same. Why? Because Balkan Plovdiv relates to Vienna as Vienna relates to New York.

But these are all empty talks. It is foolish to be a reformer. Let our man quietly wear his linen underpants instead of coarse ones. It is nonsense to force people into a higher level of civilization when they do not sense what it is about, when it is not demanded by their needs, their level.

Linen is uncomfortable for a person standing at a higher level. Therefore, we must wait some decades before our people feel this discomfort. Physical education and sports, which have also come from England and which provoke resistance to all coarse linen, will help us greatly.

In Loos's time, during the Secession, extremely high collars, both simple and double, pleated ones, were worn. I often heard from Loos that he introduced the low folded, semi-soft collar. It is certain that he dealt seriously with these matters, that he promoted them, just as many other good and reasonable things, for example, oatmeal, the failure and unpopularity of which troubled him even in 1923. In Words into the Void, he also harshly criticizes, for example, starched waistcoats, stiff collars, and cuffs and points to sporty Englishmen who have long since removed these excesses from their clothing.

Knitted underwear, he says, hides, of course, in our conditions a great danger. It is intended only for those who wash daily and bathe daily. And here we are at a cursed thing. Many Germans see in coarse underwear a great reason – so they do not have to wash.

Please consider this: from Germany come all the inventions that have aimed to save washing, body cleanliness. Let us just recall that celluloid underwear and rubber bras came to Vienna from Germany. It is from Germany that the assertion comes that washing is not good for health and that you can wear knitted shirts for years – until your environment forcefully forbids you to do so. An American cannot imagine a German without a gleaming but fake breastplate. This is evidenced by the caricature of Germans that American humorous magazines have created once and for all. You can recognize a German by the tip of the breastplate, which peeks out above the vest. Only one more class wears a false breastplate in American caricatures – thieves, tramps, vagabonds.

The false breastplate is a symbol of bodily uncleanliness.

And it is a shame that these false breastplates, which are a disgusting testimony to the cultural state of the entire Austrian nation – are proudly displayed at the Vienna exhibition of the year of Our Lord one thousand eight hundred and ninety-eight! And it is no less saddening that at this exhibition we see so many ties with sewn knots. They are, of course, made for ladies. But it does not matter since here it is about principle; even in Vienna, it is guessed that such ties are vulgar for men. The false breastplate and ties with sewn knots belong to the category of rubber underwear and glass brilliants.

Shoes as another component leading to construction clothing

The matter with shoes is not as simple as it seems. We can easily manage with clothing according to the command of fashion, but with strong or narrow hips, with high or low shoulders, which can easily change with a new cut, padding, or other aids. But a shoemaker must strictly adhere to the shape of the foot. If he wanted, for example, to introduce small shoes, he would have to patiently wait until the generation with big feet dies out.

No! It is not so simple with shoes. We cannot order shoes according to fashion. People do not have the same shape of foot. And now let us look for a norm! Which shape of foot should determine the work of the shoemaker? After all, he too has to strive – like other crafts – to make modern shoes. He too wants to get ahead.

So what does he do? He adheres to the foot that people of that class, which sets the tone in society, have. In the Middle Ages, it was the knights who had smaller feet than the poor laboring people. Therefore, a small foot was modern at that time, and its extension, the toe shoes, was still meant to enhance the impression of a slender foot. When then the burghers of staid demeanor came to honor, the large wide foot of the slowly and respectably walking burgher became fashionable bit by bit. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were a time of reversals in shoe fashion, caused by court life: walking lost favor and due to frequent use of litters, the small foot and the high-heeled shoe came back to rule, suitable for the park and palace, but not for the peasant's field path.

Anglo-Saxon culture, emphasizing physical exercise and horse riding, introduced the English high riding boot – even for those who did not have horses. This riding boot became a symbol of a free man who had finally overcome feudal ceremony, that is, shoes with buckles, courtly airs, and slippery parquet floors. This boot – a true athletic shoe – had low comfortable heels.

Oh, do not believe that poorly working brings joy to the shoemaker. But you force him to do so. He dreams of better leather, the best work. How gladly would he spend another day on that one pair of shoes! How reluctantly does he force his assistants to work faster, knowing that many carelessness must be overlooked in the process. But life is relentless. It no longer brings him joy in work. He must, must, and must make shoes for a certain price, and therefore he decides with a heavy heart to dismiss a good but slow assistant. For the same reason, he will begin to save on raw material. He must start with thread. But you, who find peculiar joy in having stripped another ducat from your shoemaker, you, who would easily spend that ducat for a better seat at the theater, you are the worst enemies of our craft. Bargaining and haggling demoralizes both the producer and the consumer. And yet: how good our shoes are! Our shoemakers are skilled people. They possess a lot of spirit and individuality.

Perhaps the German nation has so many good shoemakers because boys who have their heads, that is, individuality – but according to parents, a worthless boy – are threatened: “If you do not obey, you will become a shoemaker!”

A German must be able to obey. Whichever German does not learn that becomes a shoemaker. Therefore, we have so many Hans Sachs and Jakob Böhm at the sewing machines.

Shoe making is a field that cannot be “overcome” so quickly because it is bound to the function of walking and the shape of the human foot, which does not change.

And altogether with that overcoming! When it comes to women's fashion, I must remain silent. When it comes to men's fashion, I protest against frequent changes. But when it comes to overcoming – in furniture and in architecture – then I am beside myself.

A shoemaker who makes good shoes can never “overcome” those good shoes. And if I can maintain his product (since I have many shoes), they will always be modern.

Thank God, shoemakers have not yet been overcome.

And God forbid that architects design shoes. Then shoemakers would with great effort, rush – at least every two years – have to outdo themselves.

Customer: “These shoes keep pressing my toes.”

Shoemaker: “That’s this year’s fashion, others are not worn.”

Customer: “Yes, but what good is that to me if I still have my old feet from last year?”

I have shoes for twenty years and they have not gone out of fashion yet!

If I were a lover of horses, I would have the principle: Not horses at all, nor beautiful horses, but purebred, even if less attractive horses.

And according to that: Not some suitcase, but a suitcase made of the best material. Thorough for centuries.

And so I have come to the conclusion that the principle which some mentally limited member of the Jockey club has is absolutely correct. Aristocrats were indeed record-setting people; they gave only on material and precise, perfect workmanship.

Unfortunately, our Viennese environment, writes Loos, is filled with the desire to have the smallest foot and to mutilate it in narrow shoes. But already there are signs of improvement. Our social conditions force us to walk faster year by year. Time is money. Even the noble circles, thus people who always had enough time, are accelerating their pace. From slow walkers, they become runners. Even in the seventeenth century, soldiers marched in a way that would seem to us today as alternating standing on one leg, which would tire our feet accustomed to fast walking greatly. Frederick the Great's army took seventy steps in a minute. Our soldiers take one hundred and twenty.

Nations with advanced civilization walk faster than those who are lagging behind. Americans faster than Austrians, Italians, or people of the Balkan states. When we Viennese come to New York, we have the impression that something unfortunate has happened somewhere.

We walk faster, which means that we push off the ground with greater force from our toes. Indeed, our toes are becoming ever stronger. Slow walking widens the foot. Fast walking lengthens the foot and develops the toes.

In our time, the pedestrian has replaced the horseback rider. The pedestrian is the symbol of blessed Anglo-Saxonism. The motto of the next century will be: get ahead with your own strength, quickly. First were litters, then horses, and now the body itself, muscle. The days are gone when the scent of the stable was considered the most noble perfume. The rider was then the pampered darling of the national song: The Rider’s Death, The Rider’s Mistress, The Rider’s Farewell – the pedestrian was a nobody. The whole world that cared about their appearance dressed like a rider. When people wanted to dress beautifully, they wore riding coats and tails. The rider was a man of the flat land, a flat earth. He was, in cultivated type, a free English country nobleman who kept horses, rode to hunt, and chased the fox, jumping over English natural fences.

A pedestrian man, who lives in the plains, cannot need riding shoes. Whether he lives in Scotland or in the Alps, he must have laced shoes, stockings, and loose knees. A man from the plains wears smooth fabrics, a mountain man rough, home-woven materials.

Thank God we have ceased to be afraid of the mountains. Even a hundred years ago, there was tremendous fear of the mountains. Today it is considered a noble passion to climb mountains, to elevate your own body higher by your own strength. Neither can a cyclist need high boots. He wears laced shoes and high trousers to give his knees enough room when pedaling.

You see, everything comes from function!

Loos prophesied that laced shoes would dominate the next twentieth century, just as riding boots dominated the nineteenth century.

But for now, however, we wear ankle boots, he sighed in 1898!

But still, there is comfort. Physical exercises are spreading. As soon as our athletes began to wear shorts – it was clear to everyone that ankle boots are impossible. Just imagine: shorts above the knees, socks below on the feet, and the protruding ankle boots on them! Everyone immediately knew that without the merciful covering of trousers, ankle boots cannot be worn at all. For us – for modern people – ankle boots are definitively dead!

And what is interesting: the small foot, now, at the turn of the century, is going out of fashion. The English are right again. The large feet of the Englishmen and Englishwomen no longer lead us to mockery as before. Of course, we have also in the meantime become English ourselves; we walk, we climb mountains, we have bicycles, we do sports, and we have also received – horrible dictu – English feet.

And Adolf Loos mentions a letter he received from America, in which someone describes the famous gypsy Riga as follows: “Under the trousers peeped a pair of disgustingly small feet.”

Disgustingly small feet! That fits. A new expression is coming to us from America: Disgustingly small feet. Saint Clauren (a German writer of the early nineteenth century, popular with bourgeois sentimental novels), if you had lived to see that! Your male heroes could not have even small feet enough to appear like true knights, as types of noble manhood, with their small feet in the dreams of hundreds of thousands of German maidens.

For these ankle boots, Loos had a great quarrel with Viennese shoemakers. The letters from the shoemakers do not contribute at all to clarifying our (functional) perspective. Generally, these angry letters and submissions claim that the acceptance of laced shoes would severely harm Austrian shoemaking: it would push out ankle boots, which are considered Austrian national footwear. “The gentlemen shoemakers protest in vain! The metric centers of the printing black from which attacks against me and protests in their magazines are printed – will not spur Austrian ankle boots to new life!”

But we must also praise our Viennese master shoemakers. After the English shoemakers, our manufacturers certainly make the best shoes in the world. Austrians, when it comes to shoes, excel over other nations. I wonder about this, says Loos, because our shoemakers are poorly paid for their work. The audience compresses prices and the craftsmen must compensate for this in their manner of processing.

We can also learn a lot from the hatmakers’ guild, keeping in mind the clothing principle from human skin to urbanism

On further construction clothing: men’s clothing

Women’s clothing – a terrible chapter in cultural history

What is not and will never be art and what is true art

Plumbers arranging plumbing and bathrooms ought to be the most respected craftsmen in the state

Praise of technology and ancient Greece

Whipping in the temple of industrial art

Let us have respect for building materials – let us have respect for human labor

On architecture as the final article of human clothing

Socratic definition of beauty. What is modern and what is not modern

Efforts for a national style

Against ornament

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles

0

14.03.2019 | Yoshio Sakurai : Adolf Loose

0

03.11.2018 | Jana Kořínková: The Brno Works of Adolf Loos

0

13.01.2012 | Bohumil Markalous: Architectural Didactics and Pedagogy

0

30.12.2011 | Bohumil Markalous: The Social-Ethical Mission of the Architect

0

30.12.2011 | Bohumil Markalous: Is architecture art?

0

23.08.2008 | 75 years ago, architect Adolf Loos passed away

4

23.08.2008 | Adolf Loos: Ornament and Crime

0

22.08.2007 | 74 years ago, architect Adolf Loos died