Bohumil Markalous: Is architecture art?

To K Schürer’s article and to the discussion

|

I find myself in a similar position, far from considering the ordinary practical tasks of contemporary architecture as an artistic activity; while I cannot completely agree with the conclusions of the "artistic" enthusiasm for engineering and architecture as machinery (house = machine), this has its reason in my observation of the blanket use of the terms "art," "technique," "engineering," without anyone taking the effort to reflect on them, break them down, and try to assign to them that content which these worn out and discredited terms deserve, by means of which we ought to communicate today. It is possible to talk about conceptual inaccuracies on both sides, as I will soon show with examples, and this reproach cannot be spared to Doctor Schürer either.

When Schürer quotes Dagobert Frey, who speaks about the simple life space and the (which naturally merges with it) artistic space, I am unable to understand what "artistic space" is, in opposition to "non-artistic" or life space. Perhaps I do not understand it because I have clarified the concept of "artistic quality," "art" in my dissertation on Aesthetic Timology in 1911, a long time ago; back then, also with emphatic resistance against the concept of "artistic education," I showed that it is not about any art, just like in the so-called artistic industry and in a number of other endeavors, where the word art is taken directly sacrilegiously in vain.

The times and the development of things have proven me right to the extent that today, with a sense of the actual state of affairs, "art" is denied where it has hitherto existed or "was," that conversely, those performances that were once considered completely non-artistic are now regarded as artistic, and ultimately there are individuals who completely demolish the idol of art, stating simply and resolutely: art does not exist at all. "Art," this word, designation, is thus a real servant for everything, for something and nothing, a concept that has had to bear all kinds of abuses, being used by society for every activity for which it did not have another name available, especially if it concerned a skill of a higher nature, complex, unusual performances. Hence, gradually, everything that did not belong to everyday life became art: acrobatics, cooking, pastry-making; children's drawings in kindergartens became works of art; the people, of course, create artistically, have their folk art; a surgeon, a journalist, a speaker is an artist; a typesetter, if he arranges a business card or brochure well, is an artist (in graphic arts); seamstresses, milliners are artists, and Doucet or Poiret in Paris are famous artists in fashion; the young lady who embroiders is an artisan in applied arts. Sitting is, after all, as ancient an act as humanity itself. From the Paleolithic through both metal ages, millennia of Egypt, Babylon, and Assyria, Mycenaean culture, Greece, Roman Empire, the entire Middle Ages to our time, there have certainly been millions of carpenters thinking about how to construct a chair, an armchair, so that one can sit well. This millennia-old experience is given to us as language is. Yet a graduate of the Czechoslovak school of applied arts confidently believes that he can create a chair "with shapes better corresponding to our time and need," thus "in contemporary style," because he is an artist; his artistry can only be documented on the chair through formal whims, distorting the basic, ancient scheme, disrupting the elementary form, standard, or decorative additions to the point of disabling or burdening the function of sitting altogether. But such furniture is "artistic." We have "artistic education" for children, youth in schools and families, "artistic education" for adults, the broadest audience; we have not only artistic carpentry but also locksmithing, blacksmithing, jewelry making, as well as "artistic roller mills."

There is no more confused concept than "art," and it is high time to carry out a thorough revision, to eradicate its abuse, to invent new words for all activities that are closer to or further from true art.

At this point, however, we cannot undertake this work, which would be a grateful topic for an extensive treatise. Let us then immediately state the conclusion, to which all analyses and proofs would undoubtedly lead, in the form of a wish: that the concept of art be used only for those creations that arise from the highest exertion of spiritual, human potentiality, for creations that have the properties to mediate meta-physical values. (I write: meta-physical, not metaphysical.)

With this delimitation of the concept of art, we do not make any new discovery, but rather return to what art truly was once and which closer or deeper knowledge originally mediated: religion as a collection of surplus values. Art as the interpreter of the unknown historical destiny of man, art as the indicator of eternity, the mirror of the absolute.

Thus, we simultaneously have a reliable norm, a measure of artistic quality: in the presence of meta-physical values, the increase in which raises the significance, nobility of the artistic work, the power of its effect, artistic quality grows; as their reduction diminishes artistic quality, art declines, until it might sink into mere playful games of shapes and colors, rhythms, delight from the renewed recognition of reduced or multiplied characteristic elements and other such elemental factors. Thus, it will not be difficult to determine which areas of human activity will be artistic in the true sense of the word: music, poetry, painting, sculpture, and the compound structure: theater.

From the scientific standpoint of artistic timology, we indeed have to deal with a whole diverse hierarchy of artistic values, a scale, with a pyramid that carries at its peak the immortal, unique works, let’s say by Rembrandt, Beethoven, Homer, or Shakespeare, and progressively downwards, to its wide base, always greater quantities of works of other degrees and orders, until we find an innumerable amount of works of ordinary production at the bottom, also considered by the public to be artistic, verbal, painting, sculptural, musical, theatrical creations of the kind that put us in doubt as to whether they still deserve the title of artistic creation. This does not mean that every musical, artistic, verbal work has its, albeit the most trivial, place in the realm of artistic values, rather that the majority of the production called “artistic” simply belongs to the products of artistic, literary, musical taste, if not directly, then at least a step lower – to fashion.

It is evident that architecture and generally the entire field of so-called “applied art” is not artistic creation in the proper sense of the word. It is something else, related, similar, which is easily confused with art, as the public has every human skill, especially one that escapes its conception, of which it has insufficient knowledge, perceived as a wonder, as art. If we apply our norm for artistic quality to general architectural creations, we find nothing that would justify calling architecture art. Even the most ingenious urban project, an apartment building, a villa, a factory, a worker's house, a park, a garden has neither the necessary artistic surplus value externally nor internally based on our reasoning. Neither does the Legiobanka nor the Riunione, let alone a chair, a sideboard, a cut glass, or a painted candy box from Artěl.

This does not signify a diminishment of architecture to a lower order activity, but merely a repositioning in the domain of its significance and self-sufficiency. Here we are dealing with a vast area of taste values, values that make up in our practical lives a whole inconceivable scale, a hierarchy of taste values, with their highest repositioning in the domain of its meaning and self-sufficiency. Here we have to deal with a comprehensive area of taste values that constitute in our practical life volumes, proportions, dimensions, ratios of articles, lighting, natural or artificial environments, and all those factors that are apparent to us, recognizable, and – in contrast to the artistic work – well understood, and thus easily accessible to scientific examination and even measurable factors that create the uniqueness of a particular building. In descent, we find, as with artistic works, always a greater number of architectural creations, variants of a specific, known aesthetic architectural canon, heavily dependent on general technical progress, the material used, purpose, and numerous other conditions.

The entire history of architecture testifies to us that architecture is the exclusive domain of taste, albeit highly cultivated taste, which changes and must change, from the inner need of man for change, from the rhythm of needs, from changes in purpose, from new demands, progress, decline of civilization, in a word, from material and spiritual conditions. History shows us these changes, formal, contrasting revolutions of taste just like repetitive returns, rhythmic alternation of restlessness and calm, statics and dynamics, especially in architecture, to the extent to which slower developmental changes and possibilities in sculpture (also in three-dimensional form!), but especially in painting and music cannot be well compared. The lowest layer of the cone of taste values is the fashion of attire, in which, in proportion to the position of these creations, rapid changes are most conspicuous.

Nothing changes the fact that we call a picture, a sculpture, music, a poem beautiful just as we say that an architectural creation is beautiful, or that a table, cupboard, glass, garment is beautiful. The poverty of our language, as concerns finely felt nuances, does not make a sin here.

But the Egyptian pyramids, the Parthenon, Notre Dame! Even these unique monuments are created by supreme, noble taste and not by artistic or even “religiously passionate souls of devout humble creators.” Yes! Even in the realm of supreme taste, geniuses are at work. The reverence and wonder for the mythical, genius creators of these buildings, which exist today in our hearts and minds, is indeed in stark contrast to the former sober thinking of the creators, their architectural logic and factual reasoning. For there lies an essential difference between artistic and architectural creation. Great artistic works arise (very often, perhaps always) from psychological states that are far removed from sobriety, the intellectual balance necessary for successful architectural activity. No architecture has yet risen from Dionysian, erotic, or religious intoxication. This does not deny the influence of the social, spiritual, and religious atmosphere of the time, nor does it place the architect's activity exclusively on an intellectual basis and deny the participation of emotion, instinct, dark sources, the subconscious, invention, combination, happy inspiration, aesthetic fancy, as well as moral enjoyment – factors with which, after all, we encounter in every human activity, not excluding even the driest administrative, commercial, scientific activities, provided they are indeed initiative and not exclusively mechanical.

Thus, we would find ourselves in the creative activity of engineering. Then Doctor Oskar Schürer states literally: "It is a question of how much the forms (of purely engineering work) owe solely to purposes, static calculations, economic considerations, and how much to free artistic creation, which participates even in strict engineering constructions." From our perspective, we must emphatically object to considering a formal change made by the designer, engineer, for a better aesthetic appearance as artistic creation, just as one cannot regard the cheerful coating of Kovarik's harvesters as any artistic act – an adjustment that, after all, is made by every housewife on a dish of food before it is brought to the table.

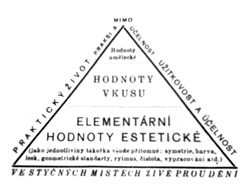

Everyone, even the most primitive person, has aesthetic requirements, feelings, their personal, subjective, which, at their core, have general constants common to all people. Otherwise, judgments could not be made with a claim to a more general validity and aesthetics as a science would not be possible. In all actions, in all life tasks, acts, work, there is reference to this personal and interpersonal social system of aesthetic values, and it is about what the quantity and quality of this set is in a given case. In sum, we can roughly set three fields, in a triangle, that likewise shows us the actual, practical expansion of the individual sections that have been discussed in this article.

A few more words should be said about the subjectively aesthetic, artistic transposition within the observer. The objectively recognized world of artistic creations, taste-related and those particularly capable of providing elementary aesthetic experiences can be subjectively (by the artist or non-artist) expanded, multiplied beyond all boundaries and regardless of our classification. A fairground figurine, a glove, a glass of water can be seen under special circumstances, internal dispositions, changes in visual perception as mysterious or artistic objects, even if they are not objectively so; even the most banal architectural creations of the outskirts of Prague can artistically act as highly dramatic backdrops to human lives, just by being what they are. And it is not excluded that the influence of certain literary and artistic musical works (Carco, Šrámek, Utrillo, Burian) suggests this perception to a broader circle, that is, it becomes more general for a time. In this way, we can explain how more influential individuals (artistically unproductive individuals only in a narrow and closest circle) or a certain group of artists can change the public's perception of things or events of the external world and instantaneously create aesthetic, even artistically subjective values in areas where there were none before.

Thus, it is now also the case with all engineering creations that suddenly find an unprecedented number of aesthetic admirers. Machines enjoy extraordinary attention from laypeople, photographers, film directors. This is correct except that the confused terminology reproduces the conceptual chaos again, speaking of engineering buildings, machines as artistic works.

If I can artistically view the dirtiest courtyard in Malá Strana, be present at a surgical operation with my mind transposed artistically or literarily, I can even more artistically observe a locomotive, a self-timer, a linotype, or a rotary press.

Let us understand clearly: objectively these things and events can never be artistic creations, subjectively, however, in mental transposition, in subjective trance, they can be just like anything else.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment