Stomping over Revoluční

Karolina Jirkalová

The project of a new building at the corner of Revoluční and Lannova streets in Prague's Petrská district appeared in the media last autumn. Today, a different solution is relevant, which does not mean the end of the discussion, but rather its reopening. It is a task that is almost the essence of the problems brought by construction in a historical environment.

The place is well visible from Letná and the left bank of the Vltava - the blind facade painted with advertisements (For the living, whatever that is.), beneath them cowers the baroque house No. 1244, to the left, a Renaissance stone water tower. The counterpart of this disordered ensemble is on the other side of Revoluční Street, the compact mass of the Merkur Palace (now Vltava) by Jaroslav Fragner. Together they create a significantly unbalanced forecourt of the Štefánik Bridge, a place that is already, at first sight, an urbanistic torso. And it doesn’t matter whether we are looking from the bridge, from Lannova Street, from Revoluční, or simply observing the footprint of the houses on the map. Even the most conservative preservationist cannot say that this is the ideal state whose form should be preserved for future generations.

How is it possible that buildings in such an exposed location show their otherwise hidden backs? As late as the beginning of the 20th century, the forecourt of the bridge was dominated by the monumental neo-Gothic building of Eliška's Baths and small houses on the other side of today's Revoluční Street. The character of the place significantly changed with the competition for ministerial buildings on the riverbank, which was won in 1920 by the design of Antonín Engel and Bohumil Hübschmann. In 1934, the small buildings opposite the baths were replaced by the generous palace of the Merkur insurance company by Jaroslav Fragner. During the Protectorate, a provisional wooden bridge was constructed next to the aging chain bridge, which sacrificed the building of Eliška's Baths. This revealed the adjacent side wall of the house at Revoluční 30, which suddenly found itself at the end of the street front, as well as the rear walls of the block at Revoluční 28. Since then, the Štefánik Bridge (1949-51) has been added, along with the adjacent grade-separated intersection, which occupied the site of the former Eliška's Baths.

Another theoretical option is to build a new house on the site of some historical building. The baroque house is a protected monument and, together with the New Mill Tower and the opposite Vávra House, preserves the memory of the place from the time before the regulation of the riverbank.

Instead, it is more reasonable to replace the neo-Renaissance building at Revoluční 30 with a new corner building. However, this solution is not entirely relevant from today's preservation perspective. The house itself does not have any exceptional artistic or historical value, yet it is located in the Prague Monument Reservation, where a protection regime applies to all objects. Even if we accept the replacement of the end house on Revoluční with a new object, the problems do not end – the neighboring baroque house is positioned a whole floor lower than the level of Revoluční (partially also Lannova) Street, making the connection between these two buildings very difficult. Not to mention that a purely corner building architecturally will not finish the blind rear facades peeking behind the low mass of the baroque building, and thus the question of building the courtyard still arises.

Another, unfortunately utopian variant, is to change the traffic solution of the entire right bank forecourt of the Štefánik Bridge in such a way that at least part of the site of the former Eliška's Baths is released. Then it would certainly be possible to complete the block without any heritage losses. In any case, it is good to perceive this place from a broader perspective of the space between the buildings of the former health insurance company (1927, B. Hübschmann and F. Roith) and the Ministry of Industry (1932, J. Fanta).

It is clear that over time, heritage protection grew in importance, while the radicality of purely urbanistic views weakened. However, one common feature remains. Engel and Hübschmann (as well as later Fragner) assumed that the forecourt of the bridge would ultimately form a symmetrical pair of buildings with a wide facade, framing the mouth of Revoluční Street and creating some sort of entrance gate. In proposals from the second half of the 20th century, however, the pair of identical buildings no longer figures, yet the need to balance the Merkur Palace with a similarly solid volume remains. The book of student proposals from Lábus's studio carries the telling title Novomlýnská - The Gateway of the City.

The proposal sparked resistance from the majority of preservationists - the Prague office of the National Heritage Institute did conditionally accept the proposal under certain limiting conditions, but the Scientific Council of the General Director of the NPÚ opposed it. It stated that "the submitted proposal does not address the complicated urban situation in an appropriate manner and does not create added architectural value in the designated place of the Prague Monument Reservation." However, given the assumption of "finding a solution with potentially higher architectural value," it accepts the possibility of demolishing the house at Revoluční 30. General Director of the NPÚ Naděžda Goryczková considers demolition to be "a very extreme solution, which is only possible after verifying and exhausting all possibilities of preserving the historic building."

The Expert Council for Heritage Care of the Prague City Hall reacted similarly to the Scientific Council. The experts found the proposed solution unacceptable, yet they believe the location needs to be resolved, and in the case of a new construction of "excellent architectural quality," demolition is possible. At the conclusion of the meeting, the council recommended the investor to announce an architectural competition for the project.

In an effort to obtain "architecturally quality" solutions that would pass the city hall's Expert Council, the investor invited four studios (Chalupa architekti, the DaM company, architect Martin Kotík, the V3S studio) to participate in a private selective procedure at the beginning of this year. However, it was certainly not an architectural competition, as recommended by the Expert Council - the selection had no clear assignment, conditions, jury, voting system, protocol, or evaluation… Petr Bodnár of Walter Titze, however, engaged a number of advisors with whom he consulted the submitted proposals. Among them were architects Josef Pleskot, Jakub Cigler, Zdeněk Fránek, Richard Sidej, and preservationists Pavel Jerie and Jan Vojta. However, we do not know other names, and the participating architects do not know them either. An important role in the selection process was played by the voice of private preservationist Josef Holeček, who had previously prepared a historical and architectural survey of the house at Revoluční 30 for the investor. Holeček is also a member of the city hall's Expert Council for Heritage Care.

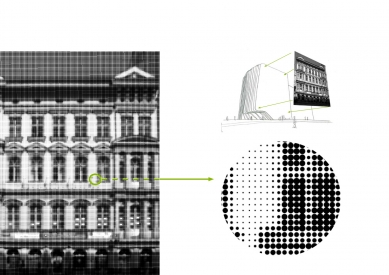

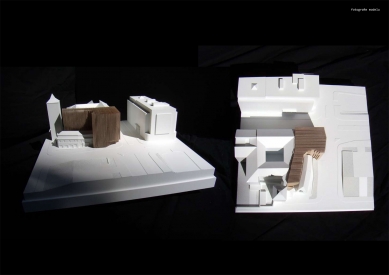

The form that emerged for the Chalupas from urban contexts, heights, and lines is surprisingly more crystalline than cubic. Thus, it is quite different from the appearance of surrounding buildings. At first glance, it may remind one of the New Stage of the National Theatre, which is not among the most beloved buildings. However, unlike Prager, the Chalupas give the building a light, bright abstract shell that is also double - the inner layer consists of supporting pillars of the entire mass, the space between them is glazed, and the outer shell is made of a "light layer of a blind-network," which unifies the facade and also prevents overheating of the interior.

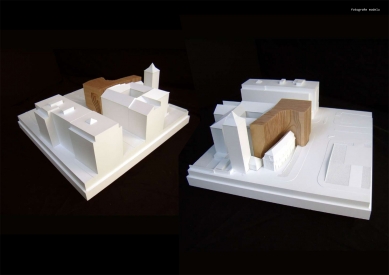

Petr Burian, among other things the author of a new residential building in Petrské Square, also started from the idea of a solid block, but proceeded differently than the Chalupas. First, he filled all the free space with the "dough of the city," as he puts it, and only then did he cut away the mass where it obstructed the surrounding buildings. Thus, he hollowed out a cavern for the baroque house and the adjacent courtyard, an arcade for pedestrians on Lannova Street, and reshaped the corner to provide better visibility into the intersection. Like the Chalupas, he breaks through the mass with a passage running from Revoluční through the courtyard to Nové Mlýny street. The courtyard wing is the same height as the corner part and is cantilevered over the courtyard above the fourth floor - essentially roofing it. A garage ramp is then placed between the baroque house and Lannova Street.

Burian's solution has a strong expressive character, rooted in the cutting away of individual layers of mass. The resulting vertical slats or plates aligned in the direction of Revoluční Street form the basis for the building's shell. It is formed in the north-south direction by ribs clad in copper or corten sheet, while the space between them is glazed. The side facades, i.e., those facing Revoluční Street and Nové Mlýny street, are covered by a protruding perforated metal shell. The author proposes that a graphic representation of the facade of the existing neo-Renaissance house should be tattooed onto the facade facing Revoluční, as a "fleeting memory." The house is, at first glance, solitary, and its dark facade and certain rawness of expression draw attention to itself. The material references late 1960s architecture, as if it were a descendant of Kotva at the other end of Revoluční Street. The concept of cuts, plates that significantly shape especially the side (eastern and western) facades, is strongly sculptural - it reminds one of layers of clay, sediment, perhaps even years of wood. Thus, it is an expressive aesthetic that has no counterpart in the broader surroundings.

Petr Burian elaborates the shell of the house in much greater detail than the Chalupa brothers, and the strength of his solution is primarily based on the concept of material concretization of the object - his presentation using the motif of slices (an exaggeration of a cut dumpling) also begins. Conversely, the Chalupas primarily focus on the precise definition of the mass and only roughly propose the facade. Nevertheless, both proposals work with an abstract shell, rather than the orderly principle of "a house with windows."

The proposals differ primarily in their degree of expression and self-centeredness and also in their respect for the surroundings, especially for the baroque house. The Chalupas propose a building that is a partner to the opposite Fragner Palace while allowing the baroque house to breathe quite freely. Moreover, they try to pull it back into the ground floor of the street. Burian shapes an unmistakable solitaire, which, viewed from the river, appears bulkier than Merkur due to the voluminous courtyard wing. The authors' report states that the new building creates for the baroque house "something akin to a calm, non-intrusive background or protective casing." It is questionable whether the small structure will be rather buried than framed by the new mass.

Of course, the investor has the right to make his own selection; he is a private investor and does not have to explain to anyone why he chose a particular proposal. The situation is, however, so sensitive that the method of selection could ultimately turn public opinion and the media against the investor, and also opens the way for speculation. If the investor had organized a public architectural competition with a reputable independent jury, he would have had a very strong argument for why the chosen building should stand at that location - because it was selected by a professional jury from many proposals as the best available solution. Moreover, as architectural historian Rostislav Švácha points out, "the city of Prague has leverage to push the investor into holding a competition - part of the plot belongs to the city - but the Prague City Hall evidently does not care about it."

How should new constructions in a historical context be evaluated? How to balance the preservation perspective with the architectural and urbanistic view? One of the most interesting questions about our contemporary relationship with the historical city arises here: Is the argument of the quality of the future building relevant in discussions about the demolition of a historic structure? Shouldn't we care only about the cultural-historical value of the original house? The argument of "exceptionally high-quality new architecture" has repeatedly been voiced in the case of Revoluční/Lannova, while heritage care, as defined by law today, cannot accept it.

On the other hand, more complex considerations about the city undoubtedly belong here. However, in a somewhat different definition. It is necessary to start from the idea formulated, for example, by the Czech-Swiss architect Miroslav Šik, as well as many others, that the basic unit of the city is not an individual house, but an ensemble (das Ensemble). A relevant argument for replacing an old building with a new construction could then sound like this: the new object will raise the quality of the entire group of buildings, including the historical structures that are part of it. It will complement the block, give meaning to individual buildings, emphasize their values, integrate the entire group into the context of the city, and establish the missing harmony. The basis for this completion of the ensemble is respect for the context, both of the ensemble itself and the broader surroundings. It is through this prism that the proposals for the corner of Revoluční and Lannova Streets should be viewed. However, this does not mean a resignation on the contemporary expression; the construction possibilities and materials are, after all, spoken of by both Burian and the Chalupas in the architectural language of today.

According to architect Josef Pleskot, who was among the investor's advisors and also on the Scientific Council, Burian's proposal is too sculptural: "It arises from its own conceptual logic, rather than from the context. Perhaps with the exception of the view from the river, for which it is primarily composed. The proposal by the Chalupa brothers, on the other hand, derives from the character of the place and has the potential to harmoniously complement it." Similarly, another member of the Scientific Council, Rostislav Švácha, views both projects: "I truly believe that the Chalupa brothers have a much more successful proposal based on a much deeper study of that place, proportional relationships between the buildings, and historical context. I think that quality did not win but the investor's feeling that architect Malinský, as chief or partner of Petr Burian, will more easily push the project through various Prague offices." Švácha refers to the fact that Petr Malinský, Burian's partner at Atelier DaM, is the chairman of the City Hall's Expert Council for Heritage Care.

Michael Zachař, director of the Prague office of the National Heritage Institute, looks more favorably on Burian's solution, but he emphasizes that this is his personal stance, not the expert opinion of the NPÚ. He likes the solitaire architecture and believes that Burian's project is beneficial in that it brings other possibilities of artistic solutions and a new aesthetic to Prague. At the same time, he adds that the domestic professional and general public is reluctant to accept such constructions and tends to accept a more moderate line closer to minimalism.

Art historian Vladimír Šlapeta also appreciates Burian's "staging of the Renaissance tower and baroque building as an assemblage that the newly completed form creates indifferent background." He states that the proposal "demonstrates the developmental possibilities of a plastic-organic mass concept as one of the possible paths in resolving complicated construction issues in a historical environment."

The city could have long since announced an ideational competition for the broader area of "Novomlýnské," which would bring a comprehensive idea of how to address the entire area, and perhaps specific regulations that potential investors should follow. The corner of Revoluční and Lannova is merely one of the questions for this location. Another is the gap at the corner of Nové Mlýny and Lannova, and considerations also arise for the construction of a small park in the middle of the road "monocle" or a change in the traffic solution. Many of these options were, in fact, verified by a competition that took place twenty years ago. However, the city hall did not make further use of its results. Today's effort to solve the problems of this area with the sandpaper of a single house is unfortunately just patchwork of the problem.

Published in the magazine Art+Antiques 12/2011, updated in January 2012

How is it possible that buildings in such an exposed location show their otherwise hidden backs? As late as the beginning of the 20th century, the forecourt of the bridge was dominated by the monumental neo-Gothic building of Eliška's Baths and small houses on the other side of today's Revoluční Street. The character of the place significantly changed with the competition for ministerial buildings on the riverbank, which was won in 1920 by the design of Antonín Engel and Bohumil Hübschmann. In 1934, the small buildings opposite the baths were replaced by the generous palace of the Merkur insurance company by Jaroslav Fragner. During the Protectorate, a provisional wooden bridge was constructed next to the aging chain bridge, which sacrificed the building of Eliška's Baths. This revealed the adjacent side wall of the house at Revoluční 30, which suddenly found itself at the end of the street front, as well as the rear walls of the block at Revoluční 28. Since then, the Štefánik Bridge (1949-51) has been added, along with the adjacent grade-separated intersection, which occupied the site of the former Eliška's Baths.

What to do with it?

Any attempt to give this place a more harmonious form encounters several problems right away. First of all, there is basically no free land here, only a narrow strip between the side wall of the neo-Renaissance house at Revoluční 30 and Lannova Street. Trying to build a house in this strip is in the category of architectural acrobatics - between the gable wall of the house and the street line defined by the Merkur Palace, there is a strip less than a meter wide, and it is roughly another five meters to the road. Moreover, this is not a building plot but a sidewalk owned by the city.Another theoretical option is to build a new house on the site of some historical building. The baroque house is a protected monument and, together with the New Mill Tower and the opposite Vávra House, preserves the memory of the place from the time before the regulation of the riverbank.

Instead, it is more reasonable to replace the neo-Renaissance building at Revoluční 30 with a new corner building. However, this solution is not entirely relevant from today's preservation perspective. The house itself does not have any exceptional artistic or historical value, yet it is located in the Prague Monument Reservation, where a protection regime applies to all objects. Even if we accept the replacement of the end house on Revoluční with a new object, the problems do not end – the neighboring baroque house is positioned a whole floor lower than the level of Revoluční (partially also Lannova) Street, making the connection between these two buildings very difficult. Not to mention that a purely corner building architecturally will not finish the blind rear facades peeking behind the low mass of the baroque building, and thus the question of building the courtyard still arises.

Another, unfortunately utopian variant, is to change the traffic solution of the entire right bank forecourt of the Štefánik Bridge in such a way that at least part of the site of the former Eliška's Baths is released. Then it would certainly be possible to complete the block without any heritage losses. In any case, it is good to perceive this place from a broader perspective of the space between the buildings of the former health insurance company (1927, B. Hübschmann and F. Roith) and the Ministry of Industry (1932, J. Fanta).

How they tried before us

Over the past fifty years, there have been countless attempts to deal with this complicated location. None of them, however, has brought a completely elegant and painless solution. In 1965, a competition was announced for an international hotel, where the design by the team of Bočan, Šrámková, and Šrámek won - the authors counted on the demolition of the entire block at the eastern mouth of Revoluční Street, including the baroque house, Vávra's house, and the former rectory, leaving only the water tower and the Church of St. Clement. In 1991, the Novomlýnská Competition took place to resolve the broader area of Lannova, Nové Mlýny, and Revoluční Streets - the demolition was no longer so extensive, as the neo-Renaissance houses Nos. 30 and 28 on Revoluční Street were to give way to new constructions. The topic of Lannova/Revoluční also appeared as a school assignment in Ladislav Lábus's studio at the Czech Technical University - the proposals are available in a Czech-Italian publication from 1996. The students' task was to solve the area using only the narrow strip along Lannova Street.It is clear that over time, heritage protection grew in importance, while the radicality of purely urbanistic views weakened. However, one common feature remains. Engel and Hübschmann (as well as later Fragner) assumed that the forecourt of the bridge would ultimately form a symmetrical pair of buildings with a wide facade, framing the mouth of Revoluční Street and creating some sort of entrance gate. In proposals from the second half of the 20th century, however, the pair of identical buildings no longer figures, yet the need to balance the Merkur Palace with a similarly solid volume remains. The book of student proposals from Lábus's studio carries the telling title Novomlýnská - The Gateway of the City.

Further development

The issue of resolving this location resurfaced last year when a proposal by the RH-Arch studio of Rostislav Říha for a new administrative building with a retail ground floor was published. The territorial study was prepared for Walter Titze, the owner of the neo-Renaissance house at Revoluční 30. Architect Říha proposed a seven-story cubic mass with a facade made of facing bricks and large glazed areas in a regular grid of steel frames, on the site of the existing building at Revoluční 30. The height of the house is based on the level of the opposite Merkur Palace. The architect situated another wing in the courtyard, which expands from the fourth floor and is cantilevered over the baroque house and over the building of the former tram depot at the water tower.The proposal sparked resistance from the majority of preservationists - the Prague office of the National Heritage Institute did conditionally accept the proposal under certain limiting conditions, but the Scientific Council of the General Director of the NPÚ opposed it. It stated that "the submitted proposal does not address the complicated urban situation in an appropriate manner and does not create added architectural value in the designated place of the Prague Monument Reservation." However, given the assumption of "finding a solution with potentially higher architectural value," it accepts the possibility of demolishing the house at Revoluční 30. General Director of the NPÚ Naděžda Goryczková considers demolition to be "a very extreme solution, which is only possible after verifying and exhausting all possibilities of preserving the historic building."

The Expert Council for Heritage Care of the Prague City Hall reacted similarly to the Scientific Council. The experts found the proposed solution unacceptable, yet they believe the location needs to be resolved, and in the case of a new construction of "excellent architectural quality," demolition is possible. At the conclusion of the meeting, the council recommended the investor to announce an architectural competition for the project.

Current situation

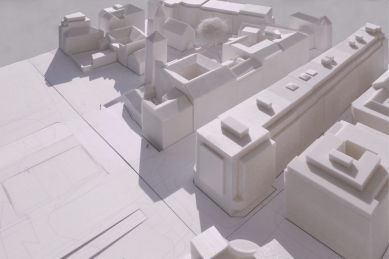

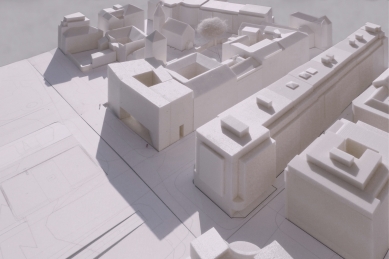

The investor commissioned another study of the area from the studio Chalupa architekti, which has experience with the new construction of the Metropol Hotel on Národní Street. However, the architects did not present the investor with a study of the house for future realization, but rather a conceptual consideration of the solution for the site. In this context, they also conducted an extensive review of previous proposals and competitions for this location (this article draws partially from it). The Chalupas concluded that if this location is to be addressed responsibly, it is not enough to focus solely on the corner of Revoluční/Lannova but it is necessary to reformulate the "facade of the city" here. They supplemented the existing structure with a new extensive block along the lines of Revoluční, Lannova, and Nové Mlýny - thus completing the ensemble, the baroque house finds itself in the courtyard, and the new building partially bridges the space above it. The solution is quite radical, yet it is based on urban contexts and the effort to complement the city's structural pattern.In an effort to obtain "architecturally quality" solutions that would pass the city hall's Expert Council, the investor invited four studios (Chalupa architekti, the DaM company, architect Martin Kotík, the V3S studio) to participate in a private selective procedure at the beginning of this year. However, it was certainly not an architectural competition, as recommended by the Expert Council - the selection had no clear assignment, conditions, jury, voting system, protocol, or evaluation… Petr Bodnár of Walter Titze, however, engaged a number of advisors with whom he consulted the submitted proposals. Among them were architects Josef Pleskot, Jakub Cigler, Zdeněk Fránek, Richard Sidej, and preservationists Pavel Jerie and Jan Vojta. However, we do not know other names, and the participating architects do not know them either. An important role in the selection process was played by the voice of private preservationist Josef Holeček, who had previously prepared a historical and architectural survey of the house at Revoluční 30 for the investor. Holeček is also a member of the city hall's Expert Council for Heritage Care.

Two in the game

Of the four proposals, two stand out in quality: those of brothers Marek and Štěpán Chalupa (Chalupa architekti) and Petr Burian (Atelier DaM). Both solutions occupy not only the plot of the house at Revoluční 30 but also the sidewalk strip in Lannova Street and part of the courtyard - both plots are owned by the city. The Chalupas, like in the previous proposal, started from an analysis of the urban situation. The mass of their building is largely defined by the height levels and building lines of the surrounding buildings. The facade facing Revoluční matches the height and composition of the existing building, then retreats from the street line and rises diagonally to the level of the Merkur Palace. From the perspective of Lannova Street and also from the bridge or Letná, a mass is created that forms an adequate counterpart to Merkur. It is cantilevered over the sidewalk in Lannova Street, where it creates a sheltered arcade, which allows the baroque house, now completely cut off from the sidewalk, to be drawn back into the ground floor. A narrow wing is proposed in the courtyard along the side blind facade of the house at Revoluční 28, which is lower than the main corner building. The courtyard space remains open, unroofed, and a passage leading through the new building from Revoluční Street opens into it.The form that emerged for the Chalupas from urban contexts, heights, and lines is surprisingly more crystalline than cubic. Thus, it is quite different from the appearance of surrounding buildings. At first glance, it may remind one of the New Stage of the National Theatre, which is not among the most beloved buildings. However, unlike Prager, the Chalupas give the building a light, bright abstract shell that is also double - the inner layer consists of supporting pillars of the entire mass, the space between them is glazed, and the outer shell is made of a "light layer of a blind-network," which unifies the facade and also prevents overheating of the interior.

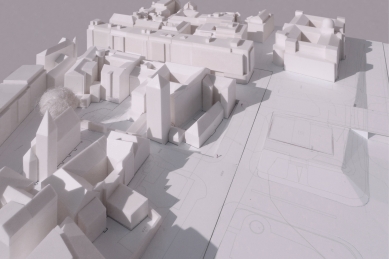

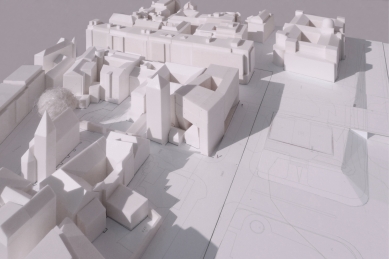

Petr Burian, among other things the author of a new residential building in Petrské Square, also started from the idea of a solid block, but proceeded differently than the Chalupas. First, he filled all the free space with the "dough of the city," as he puts it, and only then did he cut away the mass where it obstructed the surrounding buildings. Thus, he hollowed out a cavern for the baroque house and the adjacent courtyard, an arcade for pedestrians on Lannova Street, and reshaped the corner to provide better visibility into the intersection. Like the Chalupas, he breaks through the mass with a passage running from Revoluční through the courtyard to Nové Mlýny street. The courtyard wing is the same height as the corner part and is cantilevered over the courtyard above the fourth floor - essentially roofing it. A garage ramp is then placed between the baroque house and Lannova Street.

Burian's solution has a strong expressive character, rooted in the cutting away of individual layers of mass. The resulting vertical slats or plates aligned in the direction of Revoluční Street form the basis for the building's shell. It is formed in the north-south direction by ribs clad in copper or corten sheet, while the space between them is glazed. The side facades, i.e., those facing Revoluční Street and Nové Mlýny street, are covered by a protruding perforated metal shell. The author proposes that a graphic representation of the facade of the existing neo-Renaissance house should be tattooed onto the facade facing Revoluční, as a "fleeting memory." The house is, at first glance, solitary, and its dark facade and certain rawness of expression draw attention to itself. The material references late 1960s architecture, as if it were a descendant of Kotva at the other end of Revoluční Street. The concept of cuts, plates that significantly shape especially the side (eastern and western) facades, is strongly sculptural - it reminds one of layers of clay, sediment, perhaps even years of wood. Thus, it is an expressive aesthetic that has no counterpart in the broader surroundings.

Petr Burian elaborates the shell of the house in much greater detail than the Chalupa brothers, and the strength of his solution is primarily based on the concept of material concretization of the object - his presentation using the motif of slices (an exaggeration of a cut dumpling) also begins. Conversely, the Chalupas primarily focus on the precise definition of the mass and only roughly propose the facade. Nevertheless, both proposals work with an abstract shell, rather than the orderly principle of "a house with windows."

The proposals differ primarily in their degree of expression and self-centeredness and also in their respect for the surroundings, especially for the baroque house. The Chalupas propose a building that is a partner to the opposite Fragner Palace while allowing the baroque house to breathe quite freely. Moreover, they try to pull it back into the ground floor of the street. Burian shapes an unmistakable solitaire, which, viewed from the river, appears bulkier than Merkur due to the voluminous courtyard wing. The authors' report states that the new building creates for the baroque house "something akin to a calm, non-intrusive background or protective casing." It is questionable whether the small structure will be rather buried than framed by the new mass.

How to evaluate it?

Ultimately, the proposal by Petr Burian was selected for realization - unfortunately, we do not know specifically how he convinced the investor and his advisors. Pavel Brož from Walter Titze (now already from its successor company Brobosu Properties) responded to the editorial question regarding the selection: "A council of more than 50 electors was formed, divided into sections of professional public, industry public, and lay public. The proposal of architect Petr Burian from DaM received majority support in each of these three sections of the jury."Of course, the investor has the right to make his own selection; he is a private investor and does not have to explain to anyone why he chose a particular proposal. The situation is, however, so sensitive that the method of selection could ultimately turn public opinion and the media against the investor, and also opens the way for speculation. If the investor had organized a public architectural competition with a reputable independent jury, he would have had a very strong argument for why the chosen building should stand at that location - because it was selected by a professional jury from many proposals as the best available solution. Moreover, as architectural historian Rostislav Švácha points out, "the city of Prague has leverage to push the investor into holding a competition - part of the plot belongs to the city - but the Prague City Hall evidently does not care about it."

How should new constructions in a historical context be evaluated? How to balance the preservation perspective with the architectural and urbanistic view? One of the most interesting questions about our contemporary relationship with the historical city arises here: Is the argument of the quality of the future building relevant in discussions about the demolition of a historic structure? Shouldn't we care only about the cultural-historical value of the original house? The argument of "exceptionally high-quality new architecture" has repeatedly been voiced in the case of Revoluční/Lannova, while heritage care, as defined by law today, cannot accept it.

On the other hand, more complex considerations about the city undoubtedly belong here. However, in a somewhat different definition. It is necessary to start from the idea formulated, for example, by the Czech-Swiss architect Miroslav Šik, as well as many others, that the basic unit of the city is not an individual house, but an ensemble (das Ensemble). A relevant argument for replacing an old building with a new construction could then sound like this: the new object will raise the quality of the entire group of buildings, including the historical structures that are part of it. It will complement the block, give meaning to individual buildings, emphasize their values, integrate the entire group into the context of the city, and establish the missing harmony. The basis for this completion of the ensemble is respect for the context, both of the ensemble itself and the broader surroundings. It is through this prism that the proposals for the corner of Revoluční and Lannova Streets should be viewed. However, this does not mean a resignation on the contemporary expression; the construction possibilities and materials are, after all, spoken of by both Burian and the Chalupas in the architectural language of today.

Several perspectives

Preservationists disagree with Burian's proposal - according to the latest statement from the Prague office of the NPÚ, it is "excluded" as it presupposes the demolition of the structure at Revoluční 30, roofs the courtyard, and the garage ramp would eliminate "the last relic of the original level of the riverbank." The Scientific Council of the NPÚ, composed not only of preservationists but also of architects, also unanimously agreed: "The newly presented proposal does not represent added value at the given location of the Prague Monument Reservation that the house No. 1502 (Revoluční 30) should be sacrificed for."According to architect Josef Pleskot, who was among the investor's advisors and also on the Scientific Council, Burian's proposal is too sculptural: "It arises from its own conceptual logic, rather than from the context. Perhaps with the exception of the view from the river, for which it is primarily composed. The proposal by the Chalupa brothers, on the other hand, derives from the character of the place and has the potential to harmoniously complement it." Similarly, another member of the Scientific Council, Rostislav Švácha, views both projects: "I truly believe that the Chalupa brothers have a much more successful proposal based on a much deeper study of that place, proportional relationships between the buildings, and historical context. I think that quality did not win but the investor's feeling that architect Malinský, as chief or partner of Petr Burian, will more easily push the project through various Prague offices." Švácha refers to the fact that Petr Malinský, Burian's partner at Atelier DaM, is the chairman of the City Hall's Expert Council for Heritage Care.

Michael Zachař, director of the Prague office of the National Heritage Institute, looks more favorably on Burian's solution, but he emphasizes that this is his personal stance, not the expert opinion of the NPÚ. He likes the solitaire architecture and believes that Burian's project is beneficial in that it brings other possibilities of artistic solutions and a new aesthetic to Prague. At the same time, he adds that the domestic professional and general public is reluctant to accept such constructions and tends to accept a more moderate line closer to minimalism.

Art historian Vladimír Šlapeta also appreciates Burian's "staging of the Renaissance tower and baroque building as an assemblage that the newly completed form creates indifferent background." He states that the proposal "demonstrates the developmental possibilities of a plastic-organic mass concept as one of the possible paths in resolving complicated construction issues in a historical environment."

Patchwork

And the conclusion? At the beginning of November, Petr Burian's proposal was approved by the Prague Expert Council for Heritage Care, thereby opening the way for approval from the city hall's Department of Heritage Care. A broader debate will only unfold once the proposal appears in the media. It is a pity; the discussion about the potential of this complicated place and the possibilities and limits of its solutions should have preceded the emergence of proposals, not breathlessly trail behind them.The city could have long since announced an ideational competition for the broader area of "Novomlýnské," which would bring a comprehensive idea of how to address the entire area, and perhaps specific regulations that potential investors should follow. The corner of Revoluční and Lannova is merely one of the questions for this location. Another is the gap at the corner of Nové Mlýny and Lannova, and considerations also arise for the construction of a small park in the middle of the road "monocle" or a change in the traffic solution. Many of these options were, in fact, verified by a competition that took place twenty years ago. However, the city hall did not make further use of its results. Today's effort to solve the problems of this area with the sandpaper of a single house is unfortunately just patchwork of the problem.

Published in the magazine Art+Antiques 12/2011, updated in January 2012

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

7 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Tolik slov...

Jan Sommer

08.01.12 05:26

Takepamatkar Zachar vidi:

takyarchitekt

09.01.12 12:20

garmoška

soused

09.01.12 05:29

děkuji

Anna Fulíková

09.01.12 08:33

Velmi užitečný článek.

Dr.Lusciniol

10.01.12 03:34

show all comments

Related articles

9

26.03.2024 | The winner of the competition at Revoluční 30 is the Peer collective and Studio Muoto

0

06.02.2016 | The magistrate agrees to the demolition of the house on Revoluční, opposed by the NPÚ

0

20.10.2015 | The new construction project in Revoluční will apply for a zoning decision

2

19.09.2013 | The new house on Revoluční Street should be designed by Eva Jiřičná

2

11.09.2013 | <Project construction in Revoluční is coming to life, the investor has chosen a different author>

0

18.07.2013 | The Novomlýnská Gate will not be built according to the original design

0

22.05.2013 | The ministry returned the construction project on Revoluční to the magistrate

2

28.06.2012 | Investor of the construction in Revoluční must not demolish the old building

0

09.01.2012 | The architectural competition at Novomlýnská Gate did not take place