|

Driehaus Award

2003 - Léon Krier

2004 - Demetri Porphyrios

2005 - Quinlan Terry

2006 - Allan Greenberg

2007 - Jaquelin T. Robertson

2008 - Andrés Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk

|

|

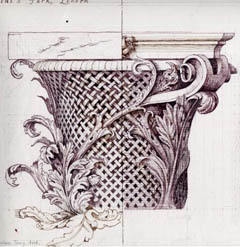

| Corinthian capital by Francis Terry |

|

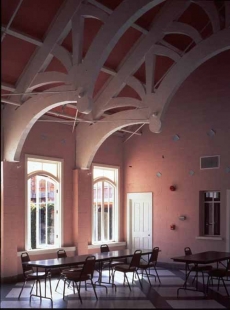

| Allan Greenberg: Humanities Building, Rice University, Houston |

|

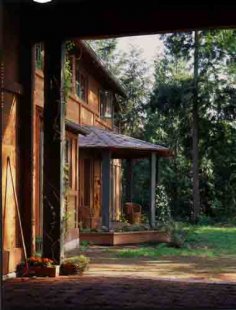

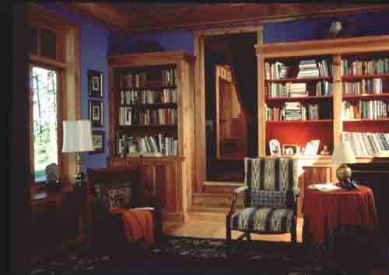

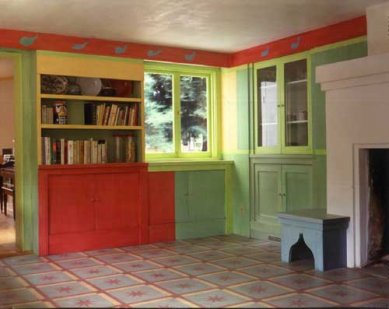

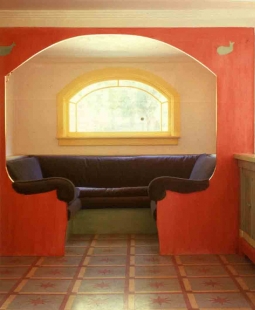

| Christopher Alexander: The Medlock House, Whidbey Island (© patternlanguage.com) |