Vlastislav Hofman: A New Principle in Architecture

Source

Časopis Styl, roč. 5 (1913), str. 13-24

Časopis Styl, roč. 5 (1913), str. 13-24

Publisher

Petr Šmídek

19.06.2013 18:00

Petr Šmídek

19.06.2013 18:00

Vlastislav Hofman

The existence of each generation has its "necessity," into which falls every unconscious mental product; here are also the foundations of creation. All activities of direct intent (e.g., speculation) and spontaneous mental activity (art) combine in the environment into a single mixture. Its tension, that is, the capability of the time. From this tension grows the art of individuals, who are its organic points. We divide art according to its principles and characteristic properties. The stimuli of art and its initiative flow from the earthly source (we still live only on earth), even though through metaphysics we relocate the soul into the realm of the unreal. Philosophy, drawing from ideas about this realm of the unreal, is distanced from art by its means, but in the end, it always has points of contact and agreement with art. With the fall of artistic epochs, there is also a disruption of philosophy; a breakdown of that necessity of being occurs; the very consequences of life’s manifestation intertwine with newly emerging possibilities and means of expression. Artists somehow secretly believe in concurrent philosophies; they cannot master them in a scientific sense, but they understand them practically, being led by feeling, and of course, they set aside many consequences, perhaps without reason, when new hypotheses are emerging and growing. The artist simply believes that modern art cannot be justified by non-modern philosophy.

Similarly, existing artistic advancements are abandoned in favor of approaching that mystery of meaning for new and different expression. The principle of rising intensity in art is the desire for unusual sensations to break the stiff mass of possibilities already achieved, which have already satiated us. In the necessity of being of each generation lies the reason for the desire for a different and new expression. It acts like physical pressure on the faculty of attainment, similar to how it affects the faculty of insight in philosophy. These are initiative environments for everything modern.

Every modern form is unusual. The unusualness of forms is what lies on the matter of the strange, which distinguishes, for example, an ancient statue from a medieval statue. This unusualness and strangeness serve as an emotional stimulus (art always shines with the luster of novelty). This novelty and real relatedness is the "taste of modernity," the original modern feeling; it was fatefully pursued by artists, whether they are significant or simply a part of the general crooked development.

The formal law is predicted (it already has its still unformed nature) and manifests itself among means and insights just being born. For example, in its age and means, our time is very complicated; the will to form plays a dangerous role here in expressing art definitely and simply.

We know the art of primitive peoples, the expression of a young thirsty organism, strong and simple; we can analyze this art somewhat formally, but we cannot quantify the reasons for its formal organization, as we lack the perception of that time. With its “taste of modernity,” we cannot digest the unique properties of primitive arts, even though we are saturating ourselves with its expressive formal interplay from historical stylistic templates that are still unknown. We also make a selection of formal interplay in historical styles, especially at the time of their first growth. (With early art, we like to identify with a certain consciousness of youth and constant beginnings.) We are surprised by the possibilities of form discovered here; we know how to see the functions of systems from history, yet despite that, we feel that their external formal character does not have the liveliness and psychic contemporaneity that we would like to have in our own expression. In short, we cannot authentically experience the medieval, Renaissance, or ancient.

Formal feeling always needs that liveliness of the "new." Its most hidden source lies in the first impressions and surprises of the individual’s life, already from the stage of childhood. (The artist is unprejudiced; imposed upbringing means little to him.) The way circumstances affect the soul is of a mysteriously intrusive, instinctual nature; circumstances act purely and immediately on the child, the first results of impressions weave into insights and the nature of feeling. A child encounters a natural phenomenon for the first time, filling with an almost poetic imagination, yet without content. If it feels the liveliness of an artificial source: the movement of mechanics, electric light, etc., it is surprised and captivated by the happenings and new possibilities in nature. A feeling arises, a peculiar mood towards new ideas (the impression of speed, sharpness, and new spaces, etc.); sensations of sensory perceptions organize themselves. The child carries within it all opportunities and experiences from youth and understands accordingly to its dispositions.

Real life, as it appears to us, and modern artistic understanding are similar; they have within them something nervously excited, fast, and uniquely tuned from the new century. Modern art of the twentieth century is against tradition in its overall average barbarism and seems contrary to it to be non-idealist (a calm era, like Biedermeier, is no longer possible today; an artistic character of similar nature would be an anachronism today). In all life processes, both calm and fleeting (the mental state of Impressionists), tragic and joyous, practical and idealistic, the artist always carries within himself the ability for formal experiences of a certain nature and the psychological formal experience given to us by life. The action of the natural source on the matter, which it is first encountering (not yet having a form organized by the artist), is already a contributor to formal feeling. It is perhaps paradoxically possible to say that “the idea lies in the matter.” This means that the notion of materiality and corporeality emphasizes the word “matter,” since it is the natural impulse to the concept of “space.” Matter, and the whole world that imposes ideas on man (ideas are not sent down to us from heaven or from the absolute) and the urge to orient and create encourages man with its ability to feel matter.

These experiences can be called an understanding of the environment; from it flows the worldview and "vision" of the artist. The feeling of this vision is then constantly in conflict with traditional capabilities; one disruption of the flowing formal feeling follows another, as the restless and insatiable human spirit requires. The feeling of matter and formal feeling thus emerge from the depths of life and from the experiences of the real environment.

The human spirit cannot be separated from nature. By its nature, we immerse ourselves in the conception and vision of the world. (The vitality of art sharply differentiates itself from expression with a prescribed artistic system, mathematical formula, rigidity, and mechanism.) A scientific formula is a theoretical certainty closed within itself; the vitality of art is a living certainty in a new conception of nature as matter.

New art uses means that are as striking and expressive as possible, thus also formally the most abstract (efforts towards a simple expression). However, it does not create abstractions, nor processes moods, rather it transforms ideas that have emerged from reality into artistic reality. To regard the spiritual principle as something that lies outside the original foundation of man, to understand it as a product of pure will, leads to academic views, which in the previous century were marked by schematism, formalism, and non-creativity. The impulse for the emergence of art is given by the vitality of feeling and not by speculation. The intellect merely utilizes these impulses practically.

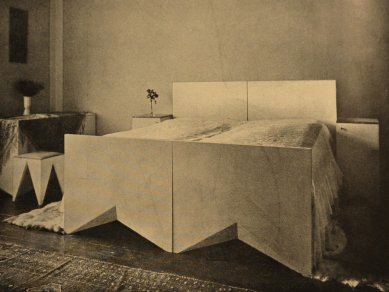

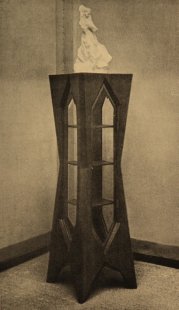

Principles as a foundational nature of art can be confirmed in both basic and minor arts. Just as formal feeling is born from life, so art is applied to every object, to the arts and crafts and to the construction of temples; in this respect, it is democratic. Today we call minor arts visual arts such as drawing, decorative, and artistic-industrial arts. Minor art is most closely linked to life, in prehistoric times it was generally connected with the first manifestations. Minor arts are products of the temporal assimilation of contemporary art. The human sense is satisfied with the emotional formal components even in the everyday course of life; there thus exists a kind of security on minor useful and only ornamental objects. From the extinct artistic epochs of nations whose culture is still too dark and unknown to history, minor art can give us at least characteristic signs of that time's art.

(We do not see individuality here.) The clearly historically stylistic era already testifies to both individual and minor art and even shows that minor art is an independent component of art in its consideration in synthesis and in its specific form. (Pompeian minor art contrasts with contemporary monumental architecture, Rococo furniture, and the Palace of Versailles; Biedermeier furniture and Greek-Classicist architecture of the time are almost mutual counterexamples.) Synthesis, a formal summary, justification, and unity of expression adheres to the psychic property of principledness of various kinds of art. Folk art is close to minor art, but it preserves within it stronger racial and self-grown roots of original creation (which constantly remain on objects and form a non-stylistic and timeless essence); minor art cannot extricate itself from the external formal character (dominants) of the basic style. However, it shows its certain property of a formative process.

The formal nature of minor art can testify to a one-dimensional formal feeling; at the same time, it does not need effects of content and poetic elements. It is rather of a light and playful nature, breaking form from feelings of whimsy and joyfully ephemeral amusement. The first expressions of prehistoric times also arose from a kind of joy from ideas, and therefore are not vague; they are synthetic and adhere to reality. (The era of painting objects and embellishing is already a second stage and insignificant for the emergence of form. In the period of stylistic art, the spirit no longer freely participates; art is not in the making here, rather it submits to the power of abstract states, such as mystery, faith, etc.)

The component of minor art can also lead to what may seem “nonsense” from the standpoint of logic and normative binding of basic art, which is not playful but monumental. To captivate with monumental art means to captivate not with a joyous feeling (spiciness, cheerfulness, swift descent, etc.), but with the feeling of some immobility, of the final, only possible and ultimate effect, where everything is evenly tied in form. The fantasy of minor art develops in relaxation, intensifies its effect for a moment of need, and allows itself to violate even the binding nature. The principled nature of minor art is precisely this aversion to monumentality.

This minor art, with its character, is not formalism. Formalism in the better sense of the word, which is not yet eclecticism, is a reaction against the rationalistic view; for formalism, the principle is “form for the sake of form.” It does not create a self-sufficient form synthetically as an impulse of formal stimuli, and loses interest in the matter from which it constructs the spaces of architecture. (I do not mean any interest in construction and material as with Wagner’s theory, but rather the coherence of the feeling of matter and form.) Forms cannot, however, be applied arbitrarily. Let us say that every matter has its cellular juice. Similarly, architecture has its principledness. Space as a unit of the concept of architecture has its capability (related to technical utilization), which lies in the core of this space. To this core, a certain specific and original form is predetermined by synthesis, and conversely, a form created for another purpose is not possible here. Formalism is a faulty motivation of principledness.

The formalist expression in the worse sense of the word is eclecticism. On a body otherwise organized (like in an Empire system), we see a mixture of forms, which have only decorative functions, against the spatial and “material” expression. (The Josephinian period and the régime style, which, one might say, hardly cares for form, is already getting rid of this eclecticism. The period of copying styles in previous development and Semper's era does not belong to the great development of architecture.) Exposed and naked matter constructed with a formal intent is capable of giving the most intensive idea of space. The "inner" form of matter is first given by its exhaustion. The line leading through the core of a Gothic rib is an abstract inner form that transforms dead matter into a living entity, approaching nature. Modern architecture also longs for such an expression. It desires the application of a sense of constructive form against the superficial form, which could be removed without loss. (The Roman from the Greek building could be removed without much damage.) A barbarically tuned sense of simple and unified understanding of space stands against the dishonesty of formalistic expression. Modern architecture does not ask for superficial shapes; therefore, it is also reluctant to contaminate form with detail. The basic shape is formed from the inner capability of matter (the idea of the movement of matter), which function is invoked by the idea of space and its interior. At the same time, the eye and its optical function in creation is merely a regulator; it does not provide the fundamental faith in creation and sometimes harms when the artist overly adheres to aesthetic sensitivity.

The principledness of different kinds of art arises when art governs its own essence in the creation of forms. In overcoming the indefinite and unformed mass into shape lies the earlier stage of merely technical overcoming that preceded it. (A chisel-shaped stone axe is already at the juncture of technique and art. Art does not commence merely when wave patterns are etched onto a vessel in a certain way or when a sword is adorned with ornaments!) In technical expressions, we recognize the functional capacity of matter in its cohesion and material binding. Artistic feeling formally connects; the architect understands space and its specific properties with a similar worldview as the engineer understands the binding of matter based on new hypotheses of science. (An architect today cannot build a Greek temple and instead use hollow concrete blocks.) Architecture organizes technical expression into a rhythmic form, thus creating its original principled relationships of spaces. These belong to the possession of art, pertain to the principle of architecture, and elude the latest scientific conclusions of technique. However, this art is filled with an unconscious awareness of combinations and capabilities of spaces; a similar awareness in new content is provided to us by technical expressions, yet its form is not led by feeling; it is an expression of science.

Rhythm changes according to the understanding and formal feeling of the time. (For example, the ancient calm rhythm is foreign to us; it is not nervously excited, as is our time. The way recent secessions have approached rhythmic values was closer to new feeling, as it was non-traditional and was a sudden outburst of an exclusive character. It is secondary that in the end it succumbed to naturalistic tendencies.) The quality of rhythm of comfortable alternation and repetition, such as in Renaissance rhyming, is merely a habitual notion of rhythm; rhythm need not be bound by these closed limits of its form. The necessary change in the rhythmic connection of forms is always dictated by a feeling of emotion, the taste of modernity.

Formal feeling always seeks new sensations. When we feel the need for new excitement after being satiated with classical ancient and Renaissance styles, we seek touches of new and unusual rhythms in the fantasy of the contemporary environment or find similarities in some other arts of the past intensely expressed. Such is primitive art and art seeking its new stylistic expression, that is, early styles. We are interested in arts where transformations and disruptions of worldview and formal feeling occur. The Middle Ages, with its Nordic and Oriental influences, are a more barbaric expression than the academic refinement of calm “architectural conditions” of the ancient school.

From the attempt for space flows the intent to strengthen plastic expressiveness through excited form against the calm and already tiring forms of antiquity. By increasing plasticity, a multiplied number of formative possibilities and tasks is achieved, which are so necessary for refreshing modern architecture. (Modern architecture of the Wagner school already fainted on a system of dead decorative surfaces, “drawings” with a one-sided view in a plane, without any movement and growth.) The growth of matter in Gothic architecture or the layered binding in Indian architecture are concepts of “binding matter,” which we feel as a contrast against the articulating ancient system. So-called architectural articulation apparatus must be cast off as unnecessary (not even suitable for educational purposes), for it appears based on principles that are already irrational for our time. The echo of modern technique already brings the sense for artistically guided constructive form; it seeks the narrowest and most uniform binding of matter and thus spatial ideas. In the sense of this standpoint, something of a sculptural nature must necessarily be applied to architecture, as it indeed wants to “shape” matter.

The effort to apply space to the architectural object emphasizes the word cube; the external appearance of architecture then appears simply treated surface areas, among organic lines of the form conception. The modern effort and sense for architectural “purity and smoothness” pertain to the nature of the taste of modernity. (The word taste must not be confused with the so-called taste, which is essentially uncreative.) The external surface appearance of modern architecture can be plain, uniformly coordinating, and somewhat austere in its distinctness. It would be illogical to burden it with every restless colorful weighting and dotted curling of ornament, as characterized by modern pseudo-folk artistic industries, for the principle of “space in matter” perhaps entirely lacks the need for decor.

Similarly, existing artistic advancements are abandoned in favor of approaching that mystery of meaning for new and different expression. The principle of rising intensity in art is the desire for unusual sensations to break the stiff mass of possibilities already achieved, which have already satiated us. In the necessity of being of each generation lies the reason for the desire for a different and new expression. It acts like physical pressure on the faculty of attainment, similar to how it affects the faculty of insight in philosophy. These are initiative environments for everything modern.

Every modern form is unusual. The unusualness of forms is what lies on the matter of the strange, which distinguishes, for example, an ancient statue from a medieval statue. This unusualness and strangeness serve as an emotional stimulus (art always shines with the luster of novelty). This novelty and real relatedness is the "taste of modernity," the original modern feeling; it was fatefully pursued by artists, whether they are significant or simply a part of the general crooked development.

The formal law is predicted (it already has its still unformed nature) and manifests itself among means and insights just being born. For example, in its age and means, our time is very complicated; the will to form plays a dangerous role here in expressing art definitely and simply.

We know the art of primitive peoples, the expression of a young thirsty organism, strong and simple; we can analyze this art somewhat formally, but we cannot quantify the reasons for its formal organization, as we lack the perception of that time. With its “taste of modernity,” we cannot digest the unique properties of primitive arts, even though we are saturating ourselves with its expressive formal interplay from historical stylistic templates that are still unknown. We also make a selection of formal interplay in historical styles, especially at the time of their first growth. (With early art, we like to identify with a certain consciousness of youth and constant beginnings.) We are surprised by the possibilities of form discovered here; we know how to see the functions of systems from history, yet despite that, we feel that their external formal character does not have the liveliness and psychic contemporaneity that we would like to have in our own expression. In short, we cannot authentically experience the medieval, Renaissance, or ancient.

Formal feeling always needs that liveliness of the "new." Its most hidden source lies in the first impressions and surprises of the individual’s life, already from the stage of childhood. (The artist is unprejudiced; imposed upbringing means little to him.) The way circumstances affect the soul is of a mysteriously intrusive, instinctual nature; circumstances act purely and immediately on the child, the first results of impressions weave into insights and the nature of feeling. A child encounters a natural phenomenon for the first time, filling with an almost poetic imagination, yet without content. If it feels the liveliness of an artificial source: the movement of mechanics, electric light, etc., it is surprised and captivated by the happenings and new possibilities in nature. A feeling arises, a peculiar mood towards new ideas (the impression of speed, sharpness, and new spaces, etc.); sensations of sensory perceptions organize themselves. The child carries within it all opportunities and experiences from youth and understands accordingly to its dispositions.

Real life, as it appears to us, and modern artistic understanding are similar; they have within them something nervously excited, fast, and uniquely tuned from the new century. Modern art of the twentieth century is against tradition in its overall average barbarism and seems contrary to it to be non-idealist (a calm era, like Biedermeier, is no longer possible today; an artistic character of similar nature would be an anachronism today). In all life processes, both calm and fleeting (the mental state of Impressionists), tragic and joyous, practical and idealistic, the artist always carries within himself the ability for formal experiences of a certain nature and the psychological formal experience given to us by life. The action of the natural source on the matter, which it is first encountering (not yet having a form organized by the artist), is already a contributor to formal feeling. It is perhaps paradoxically possible to say that “the idea lies in the matter.” This means that the notion of materiality and corporeality emphasizes the word “matter,” since it is the natural impulse to the concept of “space.” Matter, and the whole world that imposes ideas on man (ideas are not sent down to us from heaven or from the absolute) and the urge to orient and create encourages man with its ability to feel matter.

These experiences can be called an understanding of the environment; from it flows the worldview and "vision" of the artist. The feeling of this vision is then constantly in conflict with traditional capabilities; one disruption of the flowing formal feeling follows another, as the restless and insatiable human spirit requires. The feeling of matter and formal feeling thus emerge from the depths of life and from the experiences of the real environment.

The human spirit cannot be separated from nature. By its nature, we immerse ourselves in the conception and vision of the world. (The vitality of art sharply differentiates itself from expression with a prescribed artistic system, mathematical formula, rigidity, and mechanism.) A scientific formula is a theoretical certainty closed within itself; the vitality of art is a living certainty in a new conception of nature as matter.

New art uses means that are as striking and expressive as possible, thus also formally the most abstract (efforts towards a simple expression). However, it does not create abstractions, nor processes moods, rather it transforms ideas that have emerged from reality into artistic reality. To regard the spiritual principle as something that lies outside the original foundation of man, to understand it as a product of pure will, leads to academic views, which in the previous century were marked by schematism, formalism, and non-creativity. The impulse for the emergence of art is given by the vitality of feeling and not by speculation. The intellect merely utilizes these impulses practically.

Principles as a foundational nature of art can be confirmed in both basic and minor arts. Just as formal feeling is born from life, so art is applied to every object, to the arts and crafts and to the construction of temples; in this respect, it is democratic. Today we call minor arts visual arts such as drawing, decorative, and artistic-industrial arts. Minor art is most closely linked to life, in prehistoric times it was generally connected with the first manifestations. Minor arts are products of the temporal assimilation of contemporary art. The human sense is satisfied with the emotional formal components even in the everyday course of life; there thus exists a kind of security on minor useful and only ornamental objects. From the extinct artistic epochs of nations whose culture is still too dark and unknown to history, minor art can give us at least characteristic signs of that time's art.

(We do not see individuality here.) The clearly historically stylistic era already testifies to both individual and minor art and even shows that minor art is an independent component of art in its consideration in synthesis and in its specific form. (Pompeian minor art contrasts with contemporary monumental architecture, Rococo furniture, and the Palace of Versailles; Biedermeier furniture and Greek-Classicist architecture of the time are almost mutual counterexamples.) Synthesis, a formal summary, justification, and unity of expression adheres to the psychic property of principledness of various kinds of art. Folk art is close to minor art, but it preserves within it stronger racial and self-grown roots of original creation (which constantly remain on objects and form a non-stylistic and timeless essence); minor art cannot extricate itself from the external formal character (dominants) of the basic style. However, it shows its certain property of a formative process.

The formal nature of minor art can testify to a one-dimensional formal feeling; at the same time, it does not need effects of content and poetic elements. It is rather of a light and playful nature, breaking form from feelings of whimsy and joyfully ephemeral amusement. The first expressions of prehistoric times also arose from a kind of joy from ideas, and therefore are not vague; they are synthetic and adhere to reality. (The era of painting objects and embellishing is already a second stage and insignificant for the emergence of form. In the period of stylistic art, the spirit no longer freely participates; art is not in the making here, rather it submits to the power of abstract states, such as mystery, faith, etc.)

The component of minor art can also lead to what may seem “nonsense” from the standpoint of logic and normative binding of basic art, which is not playful but monumental. To captivate with monumental art means to captivate not with a joyous feeling (spiciness, cheerfulness, swift descent, etc.), but with the feeling of some immobility, of the final, only possible and ultimate effect, where everything is evenly tied in form. The fantasy of minor art develops in relaxation, intensifies its effect for a moment of need, and allows itself to violate even the binding nature. The principled nature of minor art is precisely this aversion to monumentality.

This minor art, with its character, is not formalism. Formalism in the better sense of the word, which is not yet eclecticism, is a reaction against the rationalistic view; for formalism, the principle is “form for the sake of form.” It does not create a self-sufficient form synthetically as an impulse of formal stimuli, and loses interest in the matter from which it constructs the spaces of architecture. (I do not mean any interest in construction and material as with Wagner’s theory, but rather the coherence of the feeling of matter and form.) Forms cannot, however, be applied arbitrarily. Let us say that every matter has its cellular juice. Similarly, architecture has its principledness. Space as a unit of the concept of architecture has its capability (related to technical utilization), which lies in the core of this space. To this core, a certain specific and original form is predetermined by synthesis, and conversely, a form created for another purpose is not possible here. Formalism is a faulty motivation of principledness.

The formalist expression in the worse sense of the word is eclecticism. On a body otherwise organized (like in an Empire system), we see a mixture of forms, which have only decorative functions, against the spatial and “material” expression. (The Josephinian period and the régime style, which, one might say, hardly cares for form, is already getting rid of this eclecticism. The period of copying styles in previous development and Semper's era does not belong to the great development of architecture.) Exposed and naked matter constructed with a formal intent is capable of giving the most intensive idea of space. The "inner" form of matter is first given by its exhaustion. The line leading through the core of a Gothic rib is an abstract inner form that transforms dead matter into a living entity, approaching nature. Modern architecture also longs for such an expression. It desires the application of a sense of constructive form against the superficial form, which could be removed without loss. (The Roman from the Greek building could be removed without much damage.) A barbarically tuned sense of simple and unified understanding of space stands against the dishonesty of formalistic expression. Modern architecture does not ask for superficial shapes; therefore, it is also reluctant to contaminate form with detail. The basic shape is formed from the inner capability of matter (the idea of the movement of matter), which function is invoked by the idea of space and its interior. At the same time, the eye and its optical function in creation is merely a regulator; it does not provide the fundamental faith in creation and sometimes harms when the artist overly adheres to aesthetic sensitivity.

The principledness of different kinds of art arises when art governs its own essence in the creation of forms. In overcoming the indefinite and unformed mass into shape lies the earlier stage of merely technical overcoming that preceded it. (A chisel-shaped stone axe is already at the juncture of technique and art. Art does not commence merely when wave patterns are etched onto a vessel in a certain way or when a sword is adorned with ornaments!) In technical expressions, we recognize the functional capacity of matter in its cohesion and material binding. Artistic feeling formally connects; the architect understands space and its specific properties with a similar worldview as the engineer understands the binding of matter based on new hypotheses of science. (An architect today cannot build a Greek temple and instead use hollow concrete blocks.) Architecture organizes technical expression into a rhythmic form, thus creating its original principled relationships of spaces. These belong to the possession of art, pertain to the principle of architecture, and elude the latest scientific conclusions of technique. However, this art is filled with an unconscious awareness of combinations and capabilities of spaces; a similar awareness in new content is provided to us by technical expressions, yet its form is not led by feeling; it is an expression of science.

Rhythm changes according to the understanding and formal feeling of the time. (For example, the ancient calm rhythm is foreign to us; it is not nervously excited, as is our time. The way recent secessions have approached rhythmic values was closer to new feeling, as it was non-traditional and was a sudden outburst of an exclusive character. It is secondary that in the end it succumbed to naturalistic tendencies.) The quality of rhythm of comfortable alternation and repetition, such as in Renaissance rhyming, is merely a habitual notion of rhythm; rhythm need not be bound by these closed limits of its form. The necessary change in the rhythmic connection of forms is always dictated by a feeling of emotion, the taste of modernity.

Formal feeling always seeks new sensations. When we feel the need for new excitement after being satiated with classical ancient and Renaissance styles, we seek touches of new and unusual rhythms in the fantasy of the contemporary environment or find similarities in some other arts of the past intensely expressed. Such is primitive art and art seeking its new stylistic expression, that is, early styles. We are interested in arts where transformations and disruptions of worldview and formal feeling occur. The Middle Ages, with its Nordic and Oriental influences, are a more barbaric expression than the academic refinement of calm “architectural conditions” of the ancient school.

From the attempt for space flows the intent to strengthen plastic expressiveness through excited form against the calm and already tiring forms of antiquity. By increasing plasticity, a multiplied number of formative possibilities and tasks is achieved, which are so necessary for refreshing modern architecture. (Modern architecture of the Wagner school already fainted on a system of dead decorative surfaces, “drawings” with a one-sided view in a plane, without any movement and growth.) The growth of matter in Gothic architecture or the layered binding in Indian architecture are concepts of “binding matter,” which we feel as a contrast against the articulating ancient system. So-called architectural articulation apparatus must be cast off as unnecessary (not even suitable for educational purposes), for it appears based on principles that are already irrational for our time. The echo of modern technique already brings the sense for artistically guided constructive form; it seeks the narrowest and most uniform binding of matter and thus spatial ideas. In the sense of this standpoint, something of a sculptural nature must necessarily be applied to architecture, as it indeed wants to “shape” matter.

The effort to apply space to the architectural object emphasizes the word cube; the external appearance of architecture then appears simply treated surface areas, among organic lines of the form conception. The modern effort and sense for architectural “purity and smoothness” pertain to the nature of the taste of modernity. (The word taste must not be confused with the so-called taste, which is essentially uncreative.) The external surface appearance of modern architecture can be plain, uniformly coordinating, and somewhat austere in its distinctness. It would be illogical to burden it with every restless colorful weighting and dotted curling of ornament, as characterized by modern pseudo-folk artistic industries, for the principle of “space in matter” perhaps entirely lacks the need for decor.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment