Karel Čapek and Vlastimil Hofman: Indian Architecture

Source

Časopis Styl, roč. V (1913), str. 54-92

Časopis Styl, roč. V (1913), str. 54-92

Publisher

Petr Šmídek

17.07.2013 09:00

Petr Šmídek

17.07.2013 09:00

Vlastislav Hofman

A normal European, confronted with Indian architecture, even if only in a black image, succumbs at the first moment to feelings of disorientation and confusion; his natural logic, his normal feelings, and rational alertness leave him powerless before this eruptive, hot, and astonishingly intense art. It is as if someone approached an unknown substance with the most perfect physical and technical tools, which would have different laws of resistance, weight, and movement, a different structure, impenetrability, and effectiveness than any previously known material. Indian art is for us just such a substance, for which the techniques of our thinking are inadequate and which cannot be penetrated by the critical tools of our reason.

Similarly, if we were to attempt to orient ourselves historically within Indian architecture, we would not arrive at a satisfactory understanding. Firstly, it is exceedingly difficult to ascertain even approximate historical dates for Indian buildings; even if it were possible, who could untangle the psychological, social, and ethnic factors that contributed to the creation of this art? We can immediately recognize the newer and ancient structures and intuit more or less evident Islamic and European influences, transitions to Siamese and Tibetan-Chinese architecture; however, by merely sensing these few external historical influences and their transformations, we do not comprehend; for example, the strange fact that certain original domestic Indian buildings possess in their appearance something that we cannot name otherwise than a Gothic or Romanesque character. Indian architecture, accessible to us through some kind of unified nature, presents expressions or styles that are extraordinarily complex and diverse; a historian would have to distinguish among these formal diversities not only different periods and external influences but also various internal determinations; such as the secular or ecclesiastical origin of individual stylistic motifs, the participation of higher or lower castes, local and racial specificity. Because in the melting pot of Indian culture, many nations have merged, retaining ancient instincts and capacities. India, as it exists today, is a chaos that has remained after the mixing of the oldest and most original Indo-Iranian culture with completely natural peoples. None of these original ethnic components has entirely disappeared or ceased to exert influence. Moreover, a historian would have to differentiate which religious cult was associated with which architectural style. This task would be extraordinarily difficult, because in India, there are no sharp boundaries of religion as in Europe; there, different cults have always merged, intertwined, and penetrated each other, so that even today, Hindu faith represents, on one hand, the darkest savage superstition and, on the other hand, the highest metaphysical speculation, and between these extremes lies a mix of sects and religious communities, asceticism, Yoga, and Jainism.

The most natural way for us to awaken to some understanding of Indian art is to sense the general character of its effect, that is, to determine the overall formal disposition of Indian architecture. This general psychic expression then becomes a particular mental quality of Indian art as a whole, so to speak, the collective soul of the entire Indian culture; therefore, we strive to understand the specific nature of India also from other social functions, primarily from religion and cult. Placed thus on a single common foundation of collective or social mental disposition, Indian architecture will speak to us in a more comprehensible and expressive language of forms. By comparing its forms with other arts, we will become aware of its profound distinctiveness and individuality compared to all other styles, while by accepting the specific racial and religious disposition, we will be more able to comprehend Indian architecture internally, from within.

A formal analysis of art cannot be separated from a general perspective. It has its safe and methodical means of explanation, but it easily becomes a historical narrative. In contrast, a general or comprehensive view contains more vivid elements, namely the recognition and sensation of the inner nature of the formal disposition which lies within every collective art.

Indian architecture, in its most general nature, is art that is expressive or, as it is said, effective; what immediately strikes us is the enormous intensity, while the interplay of qualities is unclear and confusing. Here, for example, we cannot pause and savor a beautiful detail, a proportionate part, in short, what might be called a qualitative architectural element. In an Indian structure, there is no central position where we could safely rest (as in classical architecture), nor a fixed point to which we might relate (as in Gothic); here, we cannot stop anywhere; we wander, disperse, and lose ourselves in countless forms that we barely grasp. The resulting feeling is always one of disorientation, amazement, and a restless whirl of sensations. Modern rationalists stand confused and astonished before this turbulent wealth of elusive forms, that are irrational, fantastic, and unpredictable as nature itself. We are not used to architecture speaking to us so hastily and excitedly; we must almost be startled by arts that can articulate something at all. This expressive intensity arises from the very vitality of Indian art. It is the condensed life of mystical India, that primordial essence which we feel in the East.

The fervor, restlessness, and excessiveness are the main mood motifs of Indian architecture. When it reminds us of nature, it is nature struggling against a terrible nightmare to awaken to consciousness; it brings to mind a kind of immense and futile fertility, as if from formless living matter, a conscious and developed being were trying to emerge into formed life, attempting to realize itself in countless shapes and experiments, only to fall back into formless dreaming. The harmony that we feel in Gothic architecture is a victory of spirit over matter; there, matter has been transformed into dizzying ideas, into conceptions purely spiritual. In contrast, disharmonious Indian architecture reminds us of the dreadful entanglement of spirit and matter; sometimes a sublime idea begins to emerge from the bubbling mass of material, one of the noblest that exist in art; sometimes an idea struggles in vain to break through the heavy veil of matter, and sometimes it seems as if matter itself were attempting to awaken to higher life, growing, pouring itself into forms, determining its being by a dark impulse like vegetation. These are, of course, only analogies; but it is difficult not to think of Indian architecture in analogies, for the demonic genius that speaks from it is not intelligibly comprehensible to us, and we can only guess at it through veils of analogy.

Thus, the question of Indian architecture demands to be supplemented by the question of a specific psychic disposition, of the spiritual environment from which this production emerges, which has presented itself to us as a pathetically disharmonious art, guided by the spirit of confusion, fantasy, and excess, in short, by a particular genius that, from our European perspective, seems darkly natural, irrational, and mysterious by definition.

Every collective art has its metaphysics. As we explain Greek art through classical vital naturalism, Romanesque art cannot be understood without the idea of Christianity, and Gothic without the triumph of faith, so each great art is the blossom of the spiritual environment, culture, and guiding ideas of its time, Indian art also has its inner metaphysics, its religious and national genius, and its psychic ground upon which we must base it in order to understand it. The overarching spirit of India, at least at the time when significant architectural monuments emerged historically, cannot be comprehended as uniformly or one-dimensionally as the cultural periods of Europe. Europe has always had very clear guiding ideas that have directed its progress and development; the delineation of periods is usually distinct, and national or class distinctions and degrees of culture can be easily isolated, which is not the case in India.

Indian religions are a mixture or alternation of elements of natural religion and philosophical, wholly abstract speculation. The most original religion, as preserved in the Vedas as a product of slow origination and composition, had the same motifs of fetishism, magic, and natural myths as most primal religions. However, the original inhabitants of India did not see as much humanity in nature as the ancient Greek; they continuously succumbed to the influence of small and evil demons, which they purchased by intoxicating them with soma’s glory, performing ritual functions, sorcery, and magical rites. More definite characteristics had the gods of natural forces, fire Agni, storm Indra, or moon Varuna, and later ethical and social deities. All these deities were often cruel tyrants, drinkers of soma, who compassionately looked down upon mortals only in their intoxication. Thus, the world was governed by despotic and lawless forces, which persisted in complete bewilderment and chaos; externally, this religion was characterized by magic and countless ritual forms in which any possible unifying and harmonious conception of a higher world and interaction with it was shattered.

However, amid this confused superstition of people who were unable to master nature and were rather dominated by it, there arose a caste of those to whom Brahma, the mystical and sacred force of direct contact with the gods, inhered. Brahmins created in the Vedas and later in the Upanishads that Indian religious speculation that is characterized by a belief in the transmigration of souls, rigorous purity of castes, and a deep aversion to nature. Nature always remained for the Indian man a confused maze of phenomena, a chaos devoid of meaning and order, mere Shakti's fleetingness that cannot be grasped.

But alongside this worldly distress and anxiety lived in him a fantastic inclination to amplify ideas into excess and boundlessness. From these two moments arose the concept of Brahma, the All-One.

Brahma is the all-substance; in Brahma, everything is the Self, Atman. Brahma is everything or everything is Atman. Whoever sees Brahma has all visible things disappear; the entire realm of phenomena remains, and only Atman, the formless Self of the world, in which everything exists, remains. In it, there is neither knowing nor imagining nor thinking; for someone thinks something, someone knows or imagines something, or according to our terminology, in all thinking and knowing, there is a subject and an object; but for Atman, there is no longer an object; in Brahma, everything seeing, knowing, imagining ends. Brahma is the negation of everything; He is "not, not." Against the glory of Brahma, the real world is merely a shadow, a veil of a phantom that envelops us.

Upon the fertile ground of India, Brahmanism astonishingly proliferated; sects of the ascetics of the Sramana state emerged, sects of ecstatics and hermits, sophists, subtle jugglers with concepts, Yoga and fakih, a great Jainism fracturing into numerous shades, and finally Buddhism. Primarily, Buddha (died 480 B.C.) the holy Sakyamuni articulated Upanishadic speculation; in his teaching, the futility and fleetingness of existence are even more emphasized, "the veil of illusion," which besets eternal nothingness, Nirvana, the end of all being and rest. His doctrine is condensed into four truths about suffering. "This is the holy truth about suffering: Birth is suffering, old age is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering, being associated with someone unpleasant is suffering, losing someone loved is suffering... This is the holy truth about the origin of suffering: it is craving, which leads from rebirth to rebirth; craving for pleasures, craving for becoming, craving for transience. This is the holy truth about the cessation of suffering: the cessation of this craving by destroying all desires, letting it go, freeing oneself from it, detaching from it, not giving it a place. This is the holy truth about the path to cessation of suffering: this is the holy eightfold path, which is called: right belief, right decision, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right thought, right immersion." Primarily, right immersion: this brings us closer to the ultimate promise of faith, to the cessation of all suffering and desire, to Nirvana. Nirvana means extinction or vanishing. Nirvana is neither "coming nor going nor standing nor dying nor being born." It is without basis, without continuation, without cessation: it is the end of suffering. Nirvana is neither life nor death; it is beyond being and non-being.

Thus, from the world of being and suffering, the only way opens to nothingness; life is but a short painful path before the return to Nirvana, and the only possibility of rest in life is to be as if we were not, to see not, to feel not, and to want not. It is understandable that for such a belief the world of physical forces, which we call nature, is a tangled web of illusions and phantoms, an uncontrollable and incomprehensible confusion that constantly passes away and never endures; it has no stability. It is a fevered vision into which we are fatally entangled and which we cannot comprehend or penetrate.

But this deep, world-renouncing Buddhist speculation was swept away by a fierce atavistic wave, whose source lay in the original natural, superstitious, and demonic instincts of the Indians, which took along the metaphysical substance of Brahmanism. It was Hinduism, a reaction against the impersonal Buddhist religion; suddenly new personal gods of enormous dimensions emerged, likely arising from the merger of old local deities, new omnipotence, entities with many heads and many arms, suffused with the flame of sensuality, cruelty, and savagery. Among these were the immense figures of Shiva and Vishnu-Krishna; Vishnu, known as the Green, the incarnation of Krishna, a violent god and, at times, a protective one, who lived as a fish, as a boar, and as the hero Rama; and Shiva, granted the fearsome name The Merciful, the cruelest being that a person could imagine, a synthesis of local demons that the original inhabitants feared, a complete mythological chaos, girded with skulls and snakes, with a trio of eyes on the forehead, a dancer, mime, and avenger. It is in this terrifying inversion or idea which we cannot grasp, that this cruel, terrible, and wicked god is the creator of the world, the god of all generation and multiplication, the originator of life; and something even stranger is that the gaze of this god-creator does not turn away from Brahma-Nirvana, from the end of all life. The ultimate meaning of life is non-being, non-thinking, non-seeing. What Christians have called the vale of tears is for an Indian always confusion of secrets, mere appearances, and incomprehensible forces, which possess no solidity. By means of Buddhism, India attempted to escape the restlessness stirred in hearts by a lawless, uncontrollable, and evil-inspired nature, to rid itself of it by denying the world and nature and resting in abstraction. But nature again broke through outwardly and poured its fevered demonic juices into the new gods of Hinduism. Hinduism remained the ruling religion, fracturing into sects and castes, incorporating new motifs from the highest speculations as well as from the darkest superstitions. Next to it, a sort of baroque, overflowing, and mystical Mahayana Buddhism persisted, Yoga and Jainism maintained, and Islam permeated from Persia. But the current religious state of India holds little interest for us, as it has ceased to be creative.

Let us cast a brief glance at Egypt. Surely the demon of the East also operated in Egypt, but it could not erupt, as it was not on such fevered ground as in India. In Egypt, the castes had an almost geometric character; everything that could stimulate fantasy and fear, primal elements of superstition, inquiries into nature, knowledge, understanding, even thought itself became the esoteric property of the priests. For the Egyptian, all secrets were securely locked away in the heads of the priests, and the priests locked them again in strict and rigid temples, in hieroglyphs, in symbols that do not speak to fantasy. Thus, at least during the time of Pharaoh's authority, all provocative, secretive, and tormenting problems were somewhat regulated and locked away. But in India, despite the purity of castes, these problems were exoteric; Nataputta, the founder of Jainism, and Buddha were worldly men. In Egypt, strict abstraction, priestly centralization, and esotericism dominated the oriental instinct of mysticism and fantasy, which was so unleashed in Indian nature. Even in Egyptian religion, there were enormous mystical secrets, but the essence of these secrets was silence, closure, and enclosure. Hence, the character of Egyptian architecture, which is a mute, uncommunicative vessel of internal mysteries. Completely different in India.

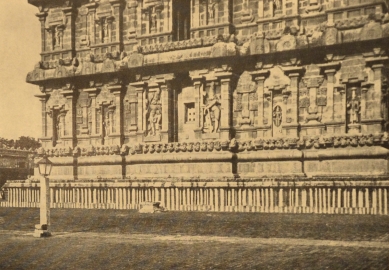

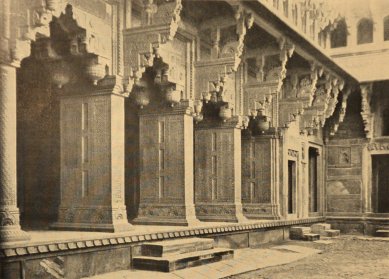

The overt sign of all Indian cults is agitation and suffering; Indian cults, mainly of a natural kind, are characterized by immense stimulation of exoteric forms of ritual, externality, fetishism, and superstition. Therefore, while Egyptian architecture is silent, Indian temples almost scream, presenting their secrets outwardly, they are not a façade, but their eruption. In particular, the sanctuaries of the Jain sect in southern India are a complete assembly of fetishes, in which each stone and each form harbors a soul.

If we compare Greek naturalism with these oriental religions, we must not limit it merely to rational knowledge of nature. The Greek was primarily a being of supreme vitality, sensual, clinging to nature with all the feelings of its pleasure and joy. It was only from this sensual and positively life-giving feeling that the Greek relationship to nature was formed. From the earliest times, nature was animated for the Greeks by human forces; they did not know of demons; their gods were kindly and powerful beings, a kind of nobility of the heavens, participating in the life of their earthly subjects. Thus, nature was favorable and accessible to man, and as soon as the sharpness of his intellect could not be satisfied merely by divine causality of natural events, he quickly began to recognize and comprehend the physical, mechanical, and astronomical laws governing the world. Undoubtedly, the Egyptian priests knew the natural laws much earlier; however, they retained them esoterically, as temple secrets, while the Greeks utilized all knowledge for the benefit of a satisfied and active existence. Egyptian science was, it seems, primarily mathematics, whose means were sacred numbers and sacred measures. In contrast, the Greeks were more mechanics and physicists; at least their architecture bears witness to an extraordinary understanding of the laws of statics, forces, motions, and optics. Thus, the Greek advanced in his worldview from a humanized nature to a nature dominated and adapted by man, recognized in its laws and obedient to rules that man could utilize. Against this knowledge, there can be no greater antithesis than the Indian understanding, for which the world was chaos and nature a playground of incomprehensible and almost unreal phenomena flitting between the soul and nothingness.

Surely, there is nothing surprising or new if we search for an artistic form's substratum in national consciousness, belief, and the species' environment in general. Forms themselves are like letters; observing these letters, we discern if the hand that wrote them was heavy or light, skillful or unskilled, elegant or laborious; from the writing, we can read the tempo, agitation, and mood. But if we wish to ask further, what governs this tempo and evokes this tuning, we inquire about the inner meaning and the guiding thoughts. The forms themselves are merely traces of the spirit that created them; however, the creating spirit itself, at least in collective arts, is found only amid a great totality of people, ideas, and feelings for whom these forms were created as their living and expressive forms.

The overall picture we have gained from the religions of the Indians is neither clear nor unified. If we abstract from doctrinal motifs, striking characteristics of Indian nature, Indian thinking, and the relationship to the world are evident: the conviction of the transience and immanent chaos of the world, confusion from the incomprehensibility and irrationality of natural phenomena, inability to dominate the world, know it, and adapt it, simplify it, impose clarity and lawfulness upon it; this is on the intellectual side; and on the emotional side, there is a fervent agitation that leads to exaggeration of ideas and to the countless forms without unifying subordination, to restlessness more numerical than quantitative, further, disharmony, torment, irregularity, inability to rejoice and to freely and willingly develop power; an intensity that is not concentrated and is flourishing, a dark impulse of tropical nature without economy and order, naturalness in the sense of blind brewing, impulsion, and growth, denying an awareness of causal and purposeful consciousness. The indigenous genius of India is as irrational as the world of phenomena that surrounds it; the Indian, who with suffering witnesses the blind and aimless whirl of natural phenomena, has himself not extricated from that confused and incomprehensible primordial nature and is subjected to it. What is in the Indian spirit intellectual is, in fact, negative, almost nihilistic, and therefore would be fundamentally anti-creative; its creative, fertile inspiration lies, accordingly, deeply in its feeling and agitation, and only in feeling. Let us recall against this that the strongest positive aspect of the Greek was in their understanding, intelligence, and actions of reason; therefore, ancient creation is rational, governed by the laws of intelligence. Thus, Indian architecture presents itself to us almost as the opposite of ancient European art.

The manner in which we interpret the forms of European architecture, and our entire traditional formal doctrine is insufficient and fundamentally inapplicable to Indian architecture. All doctrines about correctness, composition, and proportionality, European modules and ratios, even modern formal symbolism of "support and burden," which we are accustomed to use to interpret tectonics, the concept of static and dynamic forces of bearing and resting, equilibrium, and calm, our mechanics and all such concepts of perfect architecture derived from them fail when confronted with Indian art. Were anyone to wish to measure Indian architecture by these criteria, they would perceive it as nothing more than an eccentric and flawed form possessed by the demon of chaos and fantasy.

Firstly, in Indian architecture, the necessity of the laws of matter, namely the physical and mechanical laws of falling, statics, and load-bearing, that discipline or restraint of matter which was developed in antiquity is lost. These natural laws of matter can, to some extent, serve as principles of form, just as in antiquity. In antiquity, matter was dominated by the knowledge of its physical properties. Man appropriated its laws to somehow bend it to his will through agreement. Thus, the ancient form arises from an intelligent adaptation of human purpose and the natural lawfulness of matter. The precondition of antiquity is the understanding and mastery of natural forces simplified in stable laws; the second artistic precondition is that these mechanical laws and lawful forms were humanized, imbued with human vitality and nobility, and defined through optical proportion. Thus, we can imagine the synthesis of antiquity as a peaceful and non-violent amalgamation of man and nature, of human harmony and natural regularity.

India has never known such a reconciliation. The Indian man either sensed demonic forces in matter or in nature and feared it, or saw in it only an incomprehensible and nonsensical transience and turned away from it; but in whichever way, he could not master it and comprehend, nor could he recognize in it a permanent order, rule, or discipline. For example, the Indian architect did not build according to the laws of statics (but of course not against them either), but somehow outside the conception of weight, balance, and equilibrium of forces. Indian architecture (temple architecture) is not built in the sense of tectonics and statics; we feel with amazement how this artistic and religious eruption has compelled an entirely different possibility, namely architecture that is essentially sculptural. The architect, in the customary sense, preserves in his work the integrity of matter as matter, maintaining its specific material nature, its material function—such as immobility, impenetrability, weight, and resistance. In contrast, concerning a sculpture, we do not think of such material functions; a sculpture is for us a body, movement, form, something intangible that does not express weight and stability functions, which is not in any way borne up by the natural laws of matter; beneath the sculptural form, matter loses its autonomy and independence and becomes something almost other, merely a substrate. In architecture, in the general concept, matter is subdued; in sculpture, it is abolished. The natural laws of matter are simply concealed in the sculpture.

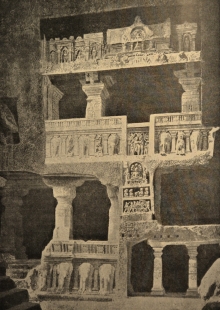

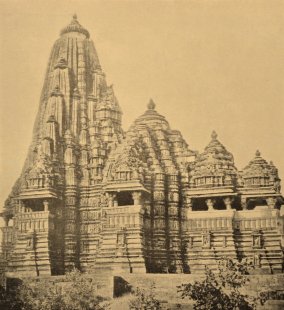

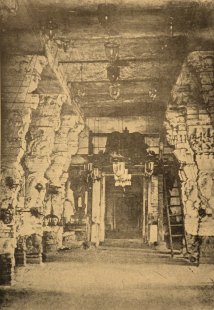

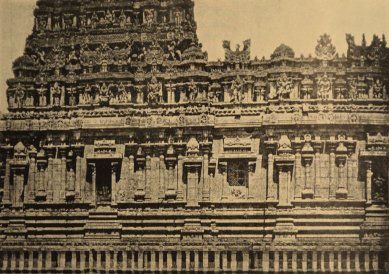

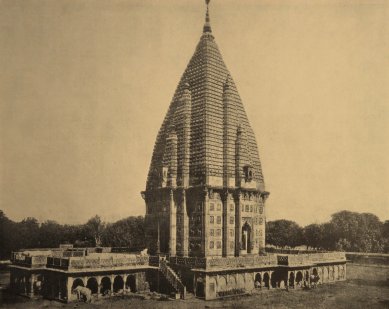

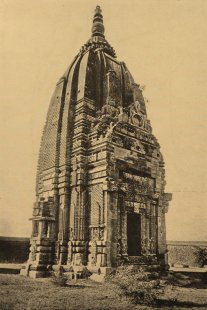

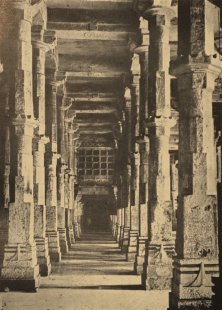

Indian architecture is sculptural. Its surface often does not exhibit even planes or walls, one of the fundamental tectonic elements; everything is a visual form, every detail is already architecture (not merely a glued-on decoration), everything is formed as a sculptor forms, not built. Indian buildings do not exhibit weight or the overcoming of weight; the intensive forces that we feel in them do not arise through load-bearing columns nor descend through burdened lintels, but emerge from the stone's interior outward as in the forms of sculptures. Nowhere do we see roofs resting on walls; above, forms and again forms of a banana shape or pointed shape emerge; for the artist who erected them wanted to construct a silhouette against the sky. The sculptural motif is also the equivalency of all details of form, whereas in pure architectural styles, the decorative detail is subordinate to the main tectonic idea. Finally, it is interesting that wherever Indian temple builders could sculpt spaces, they did so as monoliths or as rock interiors; this historically proves the sculptural path of Indian architecture.

Thus, Indian architecture is sculptural; it is not the conquering but the abolishment of matter. The physical laws of matter with which classical architecture works remain hidden and concealed in the constructed mass for the Indian; they exist in it as unretrievable and undefined mysteries that cannot break through outward through forms. The irrationality and confusion with which nature is veiled for the Indian return to our thoughts. The Indian form is something very arbitrary and lawless; sometimes it even seems to us that the form, specifically the detail, is merely a veil drawn over an internally incomprehensible and in its inner movement unpredictable mass.

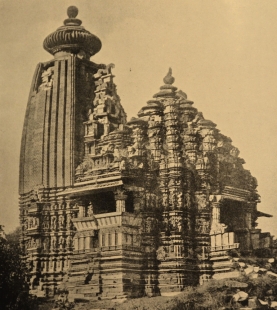

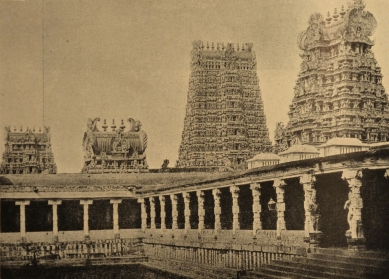

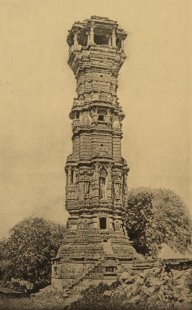

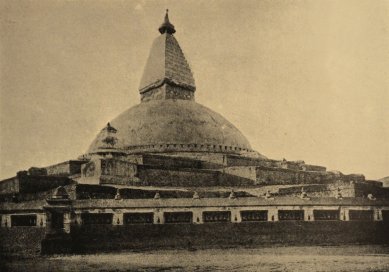

The second primary formal trait of Indian architecture, closely related to the first, is disproportion and non-geometricness. The very incomprehensibility, irregularity, and indivisibility of this multitude of forms and masses manifest a non-geometric, non-static nature, violating the basic geometric possibilities from which, for example, ancient architecture arose. Thus, the curves of Indian buildings are of arbitrary, non-mathematical degrees; the floor plans are extraordinarily complicated, and this complexity grows upwards through horizontal jointing, retreating, interpenetrating, and slanting cantilevering (overhanging masses); linear construction is pierced not by one dome, but by a whole cluster of bulging forms, as if pushed out from within like a drupe or cellular colony sprouting like mushrooms. As the opposite of geometric statics, Indian construction embodies the victory of "the principle of the movement of matter."

These disruptions of geometricality cannot be explained by the theory that art is the improvement, arrangement, and regulation of nature and physical functions; certainly, in ancient construction, we see a clear sense of regularity and necessity of nature; but here in the East, rather manifests the ability to intuitively sense the irregularity, exuberance, and unbridledness of nature, its blind impulse and spreading, transcending all, creating turmoil and heat. Here, nature contains indefinite and irreducible possibilities in infinite numbers. The awareness of this multitude of countless possibilities is so strong here that it is impossible to achieve any unity except by turning away from nature and denying reality. But even then, in religious abstraction, the oriental spirit was not freed from the bewilderment of the world; what it produces is again mysterious, complex, bubbling, and overflowing like nature, elemental and wild, irregular and countless. Indian architecture is an architectural nature completely untamed, almost unconquered by man and his harmony. Just as nature whispers and hums with musical tones of all combinations, nuances, and limits of music, the Indian architect’s melodic scale of basic tones is insufficient. The sound of Indian architecture's forms is disharmonious, shrill, and polyphonic. There is neither order nor beauty in the forms themselves; for these buildings are not erected under criteria and regulations of optical beauty, but under the pressure of religious necessity and artistic necessity simultaneously, as if they were to be perceived not by the eyes, but directly by the burning soul and wonder.

To this wonder speaks all the exaggerations of dimensions and forms, the fullness and overflowing of details, brilliance, restlessness, and monumentality. For wonder, and its disharmonious cry, resonate in the excited curves emerging from the lazy layering of the horizontal, surprising shapes of domes and tall spires and ridges. Finally, a means of wonder is what we can call spatial disorientation or stereometric disturbance.

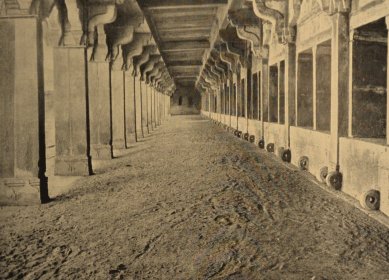

It has already been said from the beginning that observing Indian architecture can only be restless and confused, that we cannot stop anywhere and rest in the so-called main view. In our impression, some uncertainty irritates; we are disoriented, unable to precisely grasp the cuboids we see. In certain perspectives, there even occurs a perspective destruction, a violation of space, and almost an illusion of deception.

Indian architecture is akin to magical stones that change color and appearance with every turn. Nothing is certain and firmly comprehensible here; a kind of spatial deception and trickery gives these architectures a visionary character and a mysterious expression, which is a force that certainly is not incidental. Rather, we perceive in it a formal intention, namely the expression of fantasy, which does not allow for clear and calm understanding, which itself is detachment, craziness, and confusion. Here, an inner voice echoes, which speaks most fervently to internal wonder: I am reality and again non-reality, I am nature and again a vision, I stand and elude you, you cannot grasp or know me, and you can never fully comprehend me. Such are the words by which the whole world speaks to the Indian.

Primordial nature, wonder, and mystery are the innermost expressions of Indian architecture. In them, we immediately recognize the genius or demon of India, agitated and disharmonious, the great and entangled spirit of confusion and ignorance, impulse and insatiability. From building to building, we can clean the speech and emotional outpourings of this spirit; sometimes it seems to us that we already grasp its greatness, but again it slips away and loses itself in the incomprehensibility and formal labyrinth of Indian religious art.

Alongside geometrical and spatial destruction, there remains for us to speak of the destruction of matter in Indian architecture. It has already been stated that the Indian temple builder abolished matter and concealed it with sculptural form; that he did not use the laws by which matter is governed, that he did not respect the natural tectonic of matter developed in the directions of weight and resistance, horizontal burden and vertical supports.

Very often, contrary to our concept, the burden (the domed floors) is vertical, and the bearing base is sectioned horizontally; often, the shapes are pushed into each other as if they were permeable and impacted by slanted blows. Thus, the order and necessity of matter are violated; but to be violated, an enormous pressure of spiritual necessity must come, which was so strong that it did not recognize physical necessity (Indians knew the tectonic principles of matter and used them for worldly buildings. In very many illustrations, we see quite regularly executed systems of vertical direction for carrying and horizontal for burden. But it should be remembered that these are worldly buildings, princely palaces, stables, etc.; we often see on them an explicit analogy to antiquity, the renaissance, or even Romanesque styles, which is never so with temple constructions. These may rather, albeit distantly, reminisce about Gothic, Baroque, and Russian temple architecture). When we say that Indian architecture is lawless, we mean to say that it has its own lawfulness. Here arises the question of arranging and repeating forms, which no longer pertains to the sculptural character but purely to the architectural, and indeed the question of Indian understanding of its own tectonics.

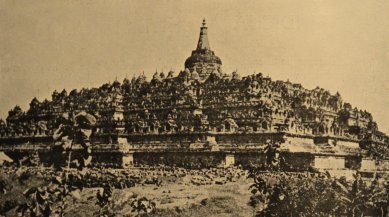

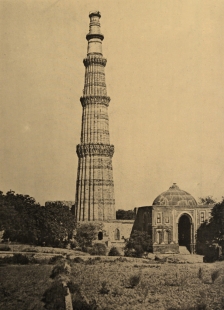

Indian architecture has a very peculiar principle of construction. Buildings are layered and nearly compacted horizontally; they grow from the earth like layers of the earth’s crust or like sediments marked by primal culture of nature. It is as if a continuation of the earth's crust, as if the underlying mass is raised through eruption to heights. One layer is placed upon another, and in this process, individual layers protrude from their composition, slanting in diagonal directions, composing whole projected surfaces, so that entire walls are thus undulated and put into an uneasy vertical motion. Thus, this horizontalism operates in both directions: monumentality and restlessness. Above, bold curves rise into entire clusters of domes as if born from one another, of uneven sizes and ages, vegetations sprouting from mud. The horizontally divided bottom is like a restlessness from which the soaring arises; or like humus from which domes draw sustenance; where there are no domes, all motifs and structures are mercilessly trimmed by horizontal jointing. Thus, by layering, summing, and multiplying layers, the building rises above and monumentality ascends in a slow, restless, and disharmonious movement. It is growth according to an arithmetic, summative series, growth of plurality and not growth of force pulled in one direction taut. The Northern spirit created Gothic in the spirit of verticalism; the Gothic dome is a single surge of force striving upward and, the further, the more tense, more insistently and increasingly, advancing somewhat geometrically. Here forms are bound by raising the mass above itself through the means of ribbed arches and verticals bearing the weight transferred into a supporting system of pillars and allowing free ascension. Horizontalism characterizes southern nations, especially India; it is the silencing and calming of the wild aggregation of mass, full of poetic delicacy of the south; it is intoxication with plurality and heavy oversaturation, it is an oriental, hot, and tiring Babylonian sentiment, the opposite of the cool, triumphant, and airy glory of the Gothic. However, what Indian architecture shares in common with Gothic is that in both the principle of the movement of matter is implemented towards the top.

Thus portrayed, the character of Indian architecture certainly applies only to temple architecture. The secular princely architecture bears a much more European character, sometimes strangely resembling antiquity or the Renaissance. In contrast, Indian temple architecture often recalls European mystical styles, Romanesque architecture, Gothic, Baroque, and Russian temple construction. For example, the Baroque style is a similar violence against matter as Indian architecture; here, the Renaissance's bearing and assembling principle of matter disappears and yields to the sculptural eloquence bursting forth from within. In Romanesque architecture, the principle of the binding of matter develops, replacing the principle of ancient tectonics. That is, the form is not extracted from the natural principles of matter, but the matter is bound by the spirit of form; it is legislated and unified in a formal sense and not in a physical sense, as some culmination of this principle of binding matter is Gothic verticalism and Indian horizontalism. Expressive intensity, amazement, and fervor make Gothic itself something akin to our Orient.

An interesting connection ties modern secession to oriental art. Namely, it is the secession's conception of a new binding of motifs; secession has replaced the system of a hundred things with an almost plant-like growth of forms, namely curves of arbitrary degree, a line that cannot be built! from mathematical construction. A similar arbitrariness of forms has been seen in non-geometric Indian art. In general, all anti-classical art is characterized by the rejection or violation of geometric forms; the very Gothic cone is a historical step toward the idea of a non-geometric, immeasurable space, as the tip of the cone here is an undefined point.

Other agreements of Indian art with European (if we abstract from the mutual historical influence of Europe and Asia) are coincidental. In ancient cultures, anticipations of future forms often appear. Many arch motifs of India possess a character of modern sensibility, as do perspective linear vanishing points and sudden shortcuts. Somewhere we discover combinations of motifs in a sort of baroque Gothic, elsewhere Romanesque, Byzantine, and so forth.

Indian architecture is not merely a historical and exotic interest to the modern man; rather, it serves as a powerful stimulus and excites him with something that we emotionally need in our rapid pace of life. Today’s person primarily finds here a penetrating intensity of expression and immense vitality, which he longs for also for his modern art. Therefore, modern man loves barbaric arts, for in them is a kind of root of the emergence of visual language, which we crave even today. We yearn for expression with accelerated tempo, however simpler and more uniform. This modern accelerated tempo will have to break through the habits that weigh it down; therefore, for the time being, in this state of tension, we love art that so stunningly overcomes European classicist conventions as Indian architecture does. Art that surprises us in this way is dear to us and facilitates our development because it reveals to us immense possibilities of creative movements entirely beyond the urges restrained by classical theories and concepts. Today, there is no style yet; but today, a kind of taste for style emerges, and thus the desire to open our kidneys to strongly affecting effects.

Similarly, if we were to attempt to orient ourselves historically within Indian architecture, we would not arrive at a satisfactory understanding. Firstly, it is exceedingly difficult to ascertain even approximate historical dates for Indian buildings; even if it were possible, who could untangle the psychological, social, and ethnic factors that contributed to the creation of this art? We can immediately recognize the newer and ancient structures and intuit more or less evident Islamic and European influences, transitions to Siamese and Tibetan-Chinese architecture; however, by merely sensing these few external historical influences and their transformations, we do not comprehend; for example, the strange fact that certain original domestic Indian buildings possess in their appearance something that we cannot name otherwise than a Gothic or Romanesque character. Indian architecture, accessible to us through some kind of unified nature, presents expressions or styles that are extraordinarily complex and diverse; a historian would have to distinguish among these formal diversities not only different periods and external influences but also various internal determinations; such as the secular or ecclesiastical origin of individual stylistic motifs, the participation of higher or lower castes, local and racial specificity. Because in the melting pot of Indian culture, many nations have merged, retaining ancient instincts and capacities. India, as it exists today, is a chaos that has remained after the mixing of the oldest and most original Indo-Iranian culture with completely natural peoples. None of these original ethnic components has entirely disappeared or ceased to exert influence. Moreover, a historian would have to differentiate which religious cult was associated with which architectural style. This task would be extraordinarily difficult, because in India, there are no sharp boundaries of religion as in Europe; there, different cults have always merged, intertwined, and penetrated each other, so that even today, Hindu faith represents, on one hand, the darkest savage superstition and, on the other hand, the highest metaphysical speculation, and between these extremes lies a mix of sects and religious communities, asceticism, Yoga, and Jainism.

The most natural way for us to awaken to some understanding of Indian art is to sense the general character of its effect, that is, to determine the overall formal disposition of Indian architecture. This general psychic expression then becomes a particular mental quality of Indian art as a whole, so to speak, the collective soul of the entire Indian culture; therefore, we strive to understand the specific nature of India also from other social functions, primarily from religion and cult. Placed thus on a single common foundation of collective or social mental disposition, Indian architecture will speak to us in a more comprehensible and expressive language of forms. By comparing its forms with other arts, we will become aware of its profound distinctiveness and individuality compared to all other styles, while by accepting the specific racial and religious disposition, we will be more able to comprehend Indian architecture internally, from within.

A formal analysis of art cannot be separated from a general perspective. It has its safe and methodical means of explanation, but it easily becomes a historical narrative. In contrast, a general or comprehensive view contains more vivid elements, namely the recognition and sensation of the inner nature of the formal disposition which lies within every collective art.

Indian architecture, in its most general nature, is art that is expressive or, as it is said, effective; what immediately strikes us is the enormous intensity, while the interplay of qualities is unclear and confusing. Here, for example, we cannot pause and savor a beautiful detail, a proportionate part, in short, what might be called a qualitative architectural element. In an Indian structure, there is no central position where we could safely rest (as in classical architecture), nor a fixed point to which we might relate (as in Gothic); here, we cannot stop anywhere; we wander, disperse, and lose ourselves in countless forms that we barely grasp. The resulting feeling is always one of disorientation, amazement, and a restless whirl of sensations. Modern rationalists stand confused and astonished before this turbulent wealth of elusive forms, that are irrational, fantastic, and unpredictable as nature itself. We are not used to architecture speaking to us so hastily and excitedly; we must almost be startled by arts that can articulate something at all. This expressive intensity arises from the very vitality of Indian art. It is the condensed life of mystical India, that primordial essence which we feel in the East.

The fervor, restlessness, and excessiveness are the main mood motifs of Indian architecture. When it reminds us of nature, it is nature struggling against a terrible nightmare to awaken to consciousness; it brings to mind a kind of immense and futile fertility, as if from formless living matter, a conscious and developed being were trying to emerge into formed life, attempting to realize itself in countless shapes and experiments, only to fall back into formless dreaming. The harmony that we feel in Gothic architecture is a victory of spirit over matter; there, matter has been transformed into dizzying ideas, into conceptions purely spiritual. In contrast, disharmonious Indian architecture reminds us of the dreadful entanglement of spirit and matter; sometimes a sublime idea begins to emerge from the bubbling mass of material, one of the noblest that exist in art; sometimes an idea struggles in vain to break through the heavy veil of matter, and sometimes it seems as if matter itself were attempting to awaken to higher life, growing, pouring itself into forms, determining its being by a dark impulse like vegetation. These are, of course, only analogies; but it is difficult not to think of Indian architecture in analogies, for the demonic genius that speaks from it is not intelligibly comprehensible to us, and we can only guess at it through veils of analogy.

Thus, the question of Indian architecture demands to be supplemented by the question of a specific psychic disposition, of the spiritual environment from which this production emerges, which has presented itself to us as a pathetically disharmonious art, guided by the spirit of confusion, fantasy, and excess, in short, by a particular genius that, from our European perspective, seems darkly natural, irrational, and mysterious by definition.

Every collective art has its metaphysics. As we explain Greek art through classical vital naturalism, Romanesque art cannot be understood without the idea of Christianity, and Gothic without the triumph of faith, so each great art is the blossom of the spiritual environment, culture, and guiding ideas of its time, Indian art also has its inner metaphysics, its religious and national genius, and its psychic ground upon which we must base it in order to understand it. The overarching spirit of India, at least at the time when significant architectural monuments emerged historically, cannot be comprehended as uniformly or one-dimensionally as the cultural periods of Europe. Europe has always had very clear guiding ideas that have directed its progress and development; the delineation of periods is usually distinct, and national or class distinctions and degrees of culture can be easily isolated, which is not the case in India.

Indian religions are a mixture or alternation of elements of natural religion and philosophical, wholly abstract speculation. The most original religion, as preserved in the Vedas as a product of slow origination and composition, had the same motifs of fetishism, magic, and natural myths as most primal religions. However, the original inhabitants of India did not see as much humanity in nature as the ancient Greek; they continuously succumbed to the influence of small and evil demons, which they purchased by intoxicating them with soma’s glory, performing ritual functions, sorcery, and magical rites. More definite characteristics had the gods of natural forces, fire Agni, storm Indra, or moon Varuna, and later ethical and social deities. All these deities were often cruel tyrants, drinkers of soma, who compassionately looked down upon mortals only in their intoxication. Thus, the world was governed by despotic and lawless forces, which persisted in complete bewilderment and chaos; externally, this religion was characterized by magic and countless ritual forms in which any possible unifying and harmonious conception of a higher world and interaction with it was shattered.

However, amid this confused superstition of people who were unable to master nature and were rather dominated by it, there arose a caste of those to whom Brahma, the mystical and sacred force of direct contact with the gods, inhered. Brahmins created in the Vedas and later in the Upanishads that Indian religious speculation that is characterized by a belief in the transmigration of souls, rigorous purity of castes, and a deep aversion to nature. Nature always remained for the Indian man a confused maze of phenomena, a chaos devoid of meaning and order, mere Shakti's fleetingness that cannot be grasped.

But alongside this worldly distress and anxiety lived in him a fantastic inclination to amplify ideas into excess and boundlessness. From these two moments arose the concept of Brahma, the All-One.

Brahma is the all-substance; in Brahma, everything is the Self, Atman. Brahma is everything or everything is Atman. Whoever sees Brahma has all visible things disappear; the entire realm of phenomena remains, and only Atman, the formless Self of the world, in which everything exists, remains. In it, there is neither knowing nor imagining nor thinking; for someone thinks something, someone knows or imagines something, or according to our terminology, in all thinking and knowing, there is a subject and an object; but for Atman, there is no longer an object; in Brahma, everything seeing, knowing, imagining ends. Brahma is the negation of everything; He is "not, not." Against the glory of Brahma, the real world is merely a shadow, a veil of a phantom that envelops us.

Upon the fertile ground of India, Brahmanism astonishingly proliferated; sects of the ascetics of the Sramana state emerged, sects of ecstatics and hermits, sophists, subtle jugglers with concepts, Yoga and fakih, a great Jainism fracturing into numerous shades, and finally Buddhism. Primarily, Buddha (died 480 B.C.) the holy Sakyamuni articulated Upanishadic speculation; in his teaching, the futility and fleetingness of existence are even more emphasized, "the veil of illusion," which besets eternal nothingness, Nirvana, the end of all being and rest. His doctrine is condensed into four truths about suffering. "This is the holy truth about suffering: Birth is suffering, old age is suffering, illness is suffering, death is suffering, being associated with someone unpleasant is suffering, losing someone loved is suffering... This is the holy truth about the origin of suffering: it is craving, which leads from rebirth to rebirth; craving for pleasures, craving for becoming, craving for transience. This is the holy truth about the cessation of suffering: the cessation of this craving by destroying all desires, letting it go, freeing oneself from it, detaching from it, not giving it a place. This is the holy truth about the path to cessation of suffering: this is the holy eightfold path, which is called: right belief, right decision, right action, right livelihood, right effort, right thought, right immersion." Primarily, right immersion: this brings us closer to the ultimate promise of faith, to the cessation of all suffering and desire, to Nirvana. Nirvana means extinction or vanishing. Nirvana is neither "coming nor going nor standing nor dying nor being born." It is without basis, without continuation, without cessation: it is the end of suffering. Nirvana is neither life nor death; it is beyond being and non-being.

Thus, from the world of being and suffering, the only way opens to nothingness; life is but a short painful path before the return to Nirvana, and the only possibility of rest in life is to be as if we were not, to see not, to feel not, and to want not. It is understandable that for such a belief the world of physical forces, which we call nature, is a tangled web of illusions and phantoms, an uncontrollable and incomprehensible confusion that constantly passes away and never endures; it has no stability. It is a fevered vision into which we are fatally entangled and which we cannot comprehend or penetrate.

But this deep, world-renouncing Buddhist speculation was swept away by a fierce atavistic wave, whose source lay in the original natural, superstitious, and demonic instincts of the Indians, which took along the metaphysical substance of Brahmanism. It was Hinduism, a reaction against the impersonal Buddhist religion; suddenly new personal gods of enormous dimensions emerged, likely arising from the merger of old local deities, new omnipotence, entities with many heads and many arms, suffused with the flame of sensuality, cruelty, and savagery. Among these were the immense figures of Shiva and Vishnu-Krishna; Vishnu, known as the Green, the incarnation of Krishna, a violent god and, at times, a protective one, who lived as a fish, as a boar, and as the hero Rama; and Shiva, granted the fearsome name The Merciful, the cruelest being that a person could imagine, a synthesis of local demons that the original inhabitants feared, a complete mythological chaos, girded with skulls and snakes, with a trio of eyes on the forehead, a dancer, mime, and avenger. It is in this terrifying inversion or idea which we cannot grasp, that this cruel, terrible, and wicked god is the creator of the world, the god of all generation and multiplication, the originator of life; and something even stranger is that the gaze of this god-creator does not turn away from Brahma-Nirvana, from the end of all life. The ultimate meaning of life is non-being, non-thinking, non-seeing. What Christians have called the vale of tears is for an Indian always confusion of secrets, mere appearances, and incomprehensible forces, which possess no solidity. By means of Buddhism, India attempted to escape the restlessness stirred in hearts by a lawless, uncontrollable, and evil-inspired nature, to rid itself of it by denying the world and nature and resting in abstraction. But nature again broke through outwardly and poured its fevered demonic juices into the new gods of Hinduism. Hinduism remained the ruling religion, fracturing into sects and castes, incorporating new motifs from the highest speculations as well as from the darkest superstitions. Next to it, a sort of baroque, overflowing, and mystical Mahayana Buddhism persisted, Yoga and Jainism maintained, and Islam permeated from Persia. But the current religious state of India holds little interest for us, as it has ceased to be creative.

Let us cast a brief glance at Egypt. Surely the demon of the East also operated in Egypt, but it could not erupt, as it was not on such fevered ground as in India. In Egypt, the castes had an almost geometric character; everything that could stimulate fantasy and fear, primal elements of superstition, inquiries into nature, knowledge, understanding, even thought itself became the esoteric property of the priests. For the Egyptian, all secrets were securely locked away in the heads of the priests, and the priests locked them again in strict and rigid temples, in hieroglyphs, in symbols that do not speak to fantasy. Thus, at least during the time of Pharaoh's authority, all provocative, secretive, and tormenting problems were somewhat regulated and locked away. But in India, despite the purity of castes, these problems were exoteric; Nataputta, the founder of Jainism, and Buddha were worldly men. In Egypt, strict abstraction, priestly centralization, and esotericism dominated the oriental instinct of mysticism and fantasy, which was so unleashed in Indian nature. Even in Egyptian religion, there were enormous mystical secrets, but the essence of these secrets was silence, closure, and enclosure. Hence, the character of Egyptian architecture, which is a mute, uncommunicative vessel of internal mysteries. Completely different in India.

The overt sign of all Indian cults is agitation and suffering; Indian cults, mainly of a natural kind, are characterized by immense stimulation of exoteric forms of ritual, externality, fetishism, and superstition. Therefore, while Egyptian architecture is silent, Indian temples almost scream, presenting their secrets outwardly, they are not a façade, but their eruption. In particular, the sanctuaries of the Jain sect in southern India are a complete assembly of fetishes, in which each stone and each form harbors a soul.

If we compare Greek naturalism with these oriental religions, we must not limit it merely to rational knowledge of nature. The Greek was primarily a being of supreme vitality, sensual, clinging to nature with all the feelings of its pleasure and joy. It was only from this sensual and positively life-giving feeling that the Greek relationship to nature was formed. From the earliest times, nature was animated for the Greeks by human forces; they did not know of demons; their gods were kindly and powerful beings, a kind of nobility of the heavens, participating in the life of their earthly subjects. Thus, nature was favorable and accessible to man, and as soon as the sharpness of his intellect could not be satisfied merely by divine causality of natural events, he quickly began to recognize and comprehend the physical, mechanical, and astronomical laws governing the world. Undoubtedly, the Egyptian priests knew the natural laws much earlier; however, they retained them esoterically, as temple secrets, while the Greeks utilized all knowledge for the benefit of a satisfied and active existence. Egyptian science was, it seems, primarily mathematics, whose means were sacred numbers and sacred measures. In contrast, the Greeks were more mechanics and physicists; at least their architecture bears witness to an extraordinary understanding of the laws of statics, forces, motions, and optics. Thus, the Greek advanced in his worldview from a humanized nature to a nature dominated and adapted by man, recognized in its laws and obedient to rules that man could utilize. Against this knowledge, there can be no greater antithesis than the Indian understanding, for which the world was chaos and nature a playground of incomprehensible and almost unreal phenomena flitting between the soul and nothingness.

Surely, there is nothing surprising or new if we search for an artistic form's substratum in national consciousness, belief, and the species' environment in general. Forms themselves are like letters; observing these letters, we discern if the hand that wrote them was heavy or light, skillful or unskilled, elegant or laborious; from the writing, we can read the tempo, agitation, and mood. But if we wish to ask further, what governs this tempo and evokes this tuning, we inquire about the inner meaning and the guiding thoughts. The forms themselves are merely traces of the spirit that created them; however, the creating spirit itself, at least in collective arts, is found only amid a great totality of people, ideas, and feelings for whom these forms were created as their living and expressive forms.

The overall picture we have gained from the religions of the Indians is neither clear nor unified. If we abstract from doctrinal motifs, striking characteristics of Indian nature, Indian thinking, and the relationship to the world are evident: the conviction of the transience and immanent chaos of the world, confusion from the incomprehensibility and irrationality of natural phenomena, inability to dominate the world, know it, and adapt it, simplify it, impose clarity and lawfulness upon it; this is on the intellectual side; and on the emotional side, there is a fervent agitation that leads to exaggeration of ideas and to the countless forms without unifying subordination, to restlessness more numerical than quantitative, further, disharmony, torment, irregularity, inability to rejoice and to freely and willingly develop power; an intensity that is not concentrated and is flourishing, a dark impulse of tropical nature without economy and order, naturalness in the sense of blind brewing, impulsion, and growth, denying an awareness of causal and purposeful consciousness. The indigenous genius of India is as irrational as the world of phenomena that surrounds it; the Indian, who with suffering witnesses the blind and aimless whirl of natural phenomena, has himself not extricated from that confused and incomprehensible primordial nature and is subjected to it. What is in the Indian spirit intellectual is, in fact, negative, almost nihilistic, and therefore would be fundamentally anti-creative; its creative, fertile inspiration lies, accordingly, deeply in its feeling and agitation, and only in feeling. Let us recall against this that the strongest positive aspect of the Greek was in their understanding, intelligence, and actions of reason; therefore, ancient creation is rational, governed by the laws of intelligence. Thus, Indian architecture presents itself to us almost as the opposite of ancient European art.

The manner in which we interpret the forms of European architecture, and our entire traditional formal doctrine is insufficient and fundamentally inapplicable to Indian architecture. All doctrines about correctness, composition, and proportionality, European modules and ratios, even modern formal symbolism of "support and burden," which we are accustomed to use to interpret tectonics, the concept of static and dynamic forces of bearing and resting, equilibrium, and calm, our mechanics and all such concepts of perfect architecture derived from them fail when confronted with Indian art. Were anyone to wish to measure Indian architecture by these criteria, they would perceive it as nothing more than an eccentric and flawed form possessed by the demon of chaos and fantasy.

Firstly, in Indian architecture, the necessity of the laws of matter, namely the physical and mechanical laws of falling, statics, and load-bearing, that discipline or restraint of matter which was developed in antiquity is lost. These natural laws of matter can, to some extent, serve as principles of form, just as in antiquity. In antiquity, matter was dominated by the knowledge of its physical properties. Man appropriated its laws to somehow bend it to his will through agreement. Thus, the ancient form arises from an intelligent adaptation of human purpose and the natural lawfulness of matter. The precondition of antiquity is the understanding and mastery of natural forces simplified in stable laws; the second artistic precondition is that these mechanical laws and lawful forms were humanized, imbued with human vitality and nobility, and defined through optical proportion. Thus, we can imagine the synthesis of antiquity as a peaceful and non-violent amalgamation of man and nature, of human harmony and natural regularity.

India has never known such a reconciliation. The Indian man either sensed demonic forces in matter or in nature and feared it, or saw in it only an incomprehensible and nonsensical transience and turned away from it; but in whichever way, he could not master it and comprehend, nor could he recognize in it a permanent order, rule, or discipline. For example, the Indian architect did not build according to the laws of statics (but of course not against them either), but somehow outside the conception of weight, balance, and equilibrium of forces. Indian architecture (temple architecture) is not built in the sense of tectonics and statics; we feel with amazement how this artistic and religious eruption has compelled an entirely different possibility, namely architecture that is essentially sculptural. The architect, in the customary sense, preserves in his work the integrity of matter as matter, maintaining its specific material nature, its material function—such as immobility, impenetrability, weight, and resistance. In contrast, concerning a sculpture, we do not think of such material functions; a sculpture is for us a body, movement, form, something intangible that does not express weight and stability functions, which is not in any way borne up by the natural laws of matter; beneath the sculptural form, matter loses its autonomy and independence and becomes something almost other, merely a substrate. In architecture, in the general concept, matter is subdued; in sculpture, it is abolished. The natural laws of matter are simply concealed in the sculpture.

Indian architecture is sculptural. Its surface often does not exhibit even planes or walls, one of the fundamental tectonic elements; everything is a visual form, every detail is already architecture (not merely a glued-on decoration), everything is formed as a sculptor forms, not built. Indian buildings do not exhibit weight or the overcoming of weight; the intensive forces that we feel in them do not arise through load-bearing columns nor descend through burdened lintels, but emerge from the stone's interior outward as in the forms of sculptures. Nowhere do we see roofs resting on walls; above, forms and again forms of a banana shape or pointed shape emerge; for the artist who erected them wanted to construct a silhouette against the sky. The sculptural motif is also the equivalency of all details of form, whereas in pure architectural styles, the decorative detail is subordinate to the main tectonic idea. Finally, it is interesting that wherever Indian temple builders could sculpt spaces, they did so as monoliths or as rock interiors; this historically proves the sculptural path of Indian architecture.

Thus, Indian architecture is sculptural; it is not the conquering but the abolishment of matter. The physical laws of matter with which classical architecture works remain hidden and concealed in the constructed mass for the Indian; they exist in it as unretrievable and undefined mysteries that cannot break through outward through forms. The irrationality and confusion with which nature is veiled for the Indian return to our thoughts. The Indian form is something very arbitrary and lawless; sometimes it even seems to us that the form, specifically the detail, is merely a veil drawn over an internally incomprehensible and in its inner movement unpredictable mass.

The second primary formal trait of Indian architecture, closely related to the first, is disproportion and non-geometricness. The very incomprehensibility, irregularity, and indivisibility of this multitude of forms and masses manifest a non-geometric, non-static nature, violating the basic geometric possibilities from which, for example, ancient architecture arose. Thus, the curves of Indian buildings are of arbitrary, non-mathematical degrees; the floor plans are extraordinarily complicated, and this complexity grows upwards through horizontal jointing, retreating, interpenetrating, and slanting cantilevering (overhanging masses); linear construction is pierced not by one dome, but by a whole cluster of bulging forms, as if pushed out from within like a drupe or cellular colony sprouting like mushrooms. As the opposite of geometric statics, Indian construction embodies the victory of "the principle of the movement of matter."

These disruptions of geometricality cannot be explained by the theory that art is the improvement, arrangement, and regulation of nature and physical functions; certainly, in ancient construction, we see a clear sense of regularity and necessity of nature; but here in the East, rather manifests the ability to intuitively sense the irregularity, exuberance, and unbridledness of nature, its blind impulse and spreading, transcending all, creating turmoil and heat. Here, nature contains indefinite and irreducible possibilities in infinite numbers. The awareness of this multitude of countless possibilities is so strong here that it is impossible to achieve any unity except by turning away from nature and denying reality. But even then, in religious abstraction, the oriental spirit was not freed from the bewilderment of the world; what it produces is again mysterious, complex, bubbling, and overflowing like nature, elemental and wild, irregular and countless. Indian architecture is an architectural nature completely untamed, almost unconquered by man and his harmony. Just as nature whispers and hums with musical tones of all combinations, nuances, and limits of music, the Indian architect’s melodic scale of basic tones is insufficient. The sound of Indian architecture's forms is disharmonious, shrill, and polyphonic. There is neither order nor beauty in the forms themselves; for these buildings are not erected under criteria and regulations of optical beauty, but under the pressure of religious necessity and artistic necessity simultaneously, as if they were to be perceived not by the eyes, but directly by the burning soul and wonder.

To this wonder speaks all the exaggerations of dimensions and forms, the fullness and overflowing of details, brilliance, restlessness, and monumentality. For wonder, and its disharmonious cry, resonate in the excited curves emerging from the lazy layering of the horizontal, surprising shapes of domes and tall spires and ridges. Finally, a means of wonder is what we can call spatial disorientation or stereometric disturbance.

It has already been said from the beginning that observing Indian architecture can only be restless and confused, that we cannot stop anywhere and rest in the so-called main view. In our impression, some uncertainty irritates; we are disoriented, unable to precisely grasp the cuboids we see. In certain perspectives, there even occurs a perspective destruction, a violation of space, and almost an illusion of deception.

Indian architecture is akin to magical stones that change color and appearance with every turn. Nothing is certain and firmly comprehensible here; a kind of spatial deception and trickery gives these architectures a visionary character and a mysterious expression, which is a force that certainly is not incidental. Rather, we perceive in it a formal intention, namely the expression of fantasy, which does not allow for clear and calm understanding, which itself is detachment, craziness, and confusion. Here, an inner voice echoes, which speaks most fervently to internal wonder: I am reality and again non-reality, I am nature and again a vision, I stand and elude you, you cannot grasp or know me, and you can never fully comprehend me. Such are the words by which the whole world speaks to the Indian.

Primordial nature, wonder, and mystery are the innermost expressions of Indian architecture. In them, we immediately recognize the genius or demon of India, agitated and disharmonious, the great and entangled spirit of confusion and ignorance, impulse and insatiability. From building to building, we can clean the speech and emotional outpourings of this spirit; sometimes it seems to us that we already grasp its greatness, but again it slips away and loses itself in the incomprehensibility and formal labyrinth of Indian religious art.

Alongside geometrical and spatial destruction, there remains for us to speak of the destruction of matter in Indian architecture. It has already been stated that the Indian temple builder abolished matter and concealed it with sculptural form; that he did not use the laws by which matter is governed, that he did not respect the natural tectonic of matter developed in the directions of weight and resistance, horizontal burden and vertical supports.

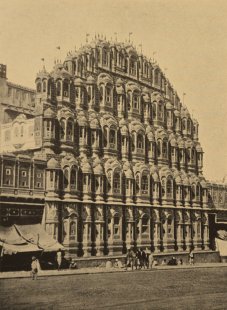

Very often, contrary to our concept, the burden (the domed floors) is vertical, and the bearing base is sectioned horizontally; often, the shapes are pushed into each other as if they were permeable and impacted by slanted blows. Thus, the order and necessity of matter are violated; but to be violated, an enormous pressure of spiritual necessity must come, which was so strong that it did not recognize physical necessity (Indians knew the tectonic principles of matter and used them for worldly buildings. In very many illustrations, we see quite regularly executed systems of vertical direction for carrying and horizontal for burden. But it should be remembered that these are worldly buildings, princely palaces, stables, etc.; we often see on them an explicit analogy to antiquity, the renaissance, or even Romanesque styles, which is never so with temple constructions. These may rather, albeit distantly, reminisce about Gothic, Baroque, and Russian temple architecture). When we say that Indian architecture is lawless, we mean to say that it has its own lawfulness. Here arises the question of arranging and repeating forms, which no longer pertains to the sculptural character but purely to the architectural, and indeed the question of Indian understanding of its own tectonics.

Indian architecture has a very peculiar principle of construction. Buildings are layered and nearly compacted horizontally; they grow from the earth like layers of the earth’s crust or like sediments marked by primal culture of nature. It is as if a continuation of the earth's crust, as if the underlying mass is raised through eruption to heights. One layer is placed upon another, and in this process, individual layers protrude from their composition, slanting in diagonal directions, composing whole projected surfaces, so that entire walls are thus undulated and put into an uneasy vertical motion. Thus, this horizontalism operates in both directions: monumentality and restlessness. Above, bold curves rise into entire clusters of domes as if born from one another, of uneven sizes and ages, vegetations sprouting from mud. The horizontally divided bottom is like a restlessness from which the soaring arises; or like humus from which domes draw sustenance; where there are no domes, all motifs and structures are mercilessly trimmed by horizontal jointing. Thus, by layering, summing, and multiplying layers, the building rises above and monumentality ascends in a slow, restless, and disharmonious movement. It is growth according to an arithmetic, summative series, growth of plurality and not growth of force pulled in one direction taut. The Northern spirit created Gothic in the spirit of verticalism; the Gothic dome is a single surge of force striving upward and, the further, the more tense, more insistently and increasingly, advancing somewhat geometrically. Here forms are bound by raising the mass above itself through the means of ribbed arches and verticals bearing the weight transferred into a supporting system of pillars and allowing free ascension. Horizontalism characterizes southern nations, especially India; it is the silencing and calming of the wild aggregation of mass, full of poetic delicacy of the south; it is intoxication with plurality and heavy oversaturation, it is an oriental, hot, and tiring Babylonian sentiment, the opposite of the cool, triumphant, and airy glory of the Gothic. However, what Indian architecture shares in common with Gothic is that in both the principle of the movement of matter is implemented towards the top.

Thus portrayed, the character of Indian architecture certainly applies only to temple architecture. The secular princely architecture bears a much more European character, sometimes strangely resembling antiquity or the Renaissance. In contrast, Indian temple architecture often recalls European mystical styles, Romanesque architecture, Gothic, Baroque, and Russian temple construction. For example, the Baroque style is a similar violence against matter as Indian architecture; here, the Renaissance's bearing and assembling principle of matter disappears and yields to the sculptural eloquence bursting forth from within. In Romanesque architecture, the principle of the binding of matter develops, replacing the principle of ancient tectonics. That is, the form is not extracted from the natural principles of matter, but the matter is bound by the spirit of form; it is legislated and unified in a formal sense and not in a physical sense, as some culmination of this principle of binding matter is Gothic verticalism and Indian horizontalism. Expressive intensity, amazement, and fervor make Gothic itself something akin to our Orient.

An interesting connection ties modern secession to oriental art. Namely, it is the secession's conception of a new binding of motifs; secession has replaced the system of a hundred things with an almost plant-like growth of forms, namely curves of arbitrary degree, a line that cannot be built! from mathematical construction. A similar arbitrariness of forms has been seen in non-geometric Indian art. In general, all anti-classical art is characterized by the rejection or violation of geometric forms; the very Gothic cone is a historical step toward the idea of a non-geometric, immeasurable space, as the tip of the cone here is an undefined point.

Other agreements of Indian art with European (if we abstract from the mutual historical influence of Europe and Asia) are coincidental. In ancient cultures, anticipations of future forms often appear. Many arch motifs of India possess a character of modern sensibility, as do perspective linear vanishing points and sudden shortcuts. Somewhere we discover combinations of motifs in a sort of baroque Gothic, elsewhere Romanesque, Byzantine, and so forth.

Indian architecture is not merely a historical and exotic interest to the modern man; rather, it serves as a powerful stimulus and excites him with something that we emotionally need in our rapid pace of life. Today’s person primarily finds here a penetrating intensity of expression and immense vitality, which he longs for also for his modern art. Therefore, modern man loves barbaric arts, for in them is a kind of root of the emergence of visual language, which we crave even today. We yearn for expression with accelerated tempo, however simpler and more uniform. This modern accelerated tempo will have to break through the habits that weigh it down; therefore, for the time being, in this state of tension, we love art that so stunningly overcomes European classicist conventions as Indian architecture does. Art that surprises us in this way is dear to us and facilitates our development because it reveals to us immense possibilities of creative movements entirely beyond the urges restrained by classical theories and concepts. Today, there is no style yet; but today, a kind of taste for style emerges, and thus the desire to open our kidneys to strongly affecting effects.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment