Kunsthalle in Žilina or the life of one synagogue

When Slovakia is mentioned, most people imagine rather beautiful natural scenery than cultural monuments that transcend the significance of the borders of this state. However, such monuments can also be found here, although awareness of them is very low even among Slovaks themselves. And just as Brno boasts the Tugendhat Villa by Mies van der Rohe, the city of Žilina could base its cultural promotion on the local neolog synagogue designed by German architect and designer Peter Behrens. This gem of European modern architecture will come to life again in the near future, and we will definitely hear more about it. Not only is it undergoing renovation similar to the Brno Tugendhat Villa, but it is also highly likely that the long-missed kunsthalle project will finally take place here in Slovakia.

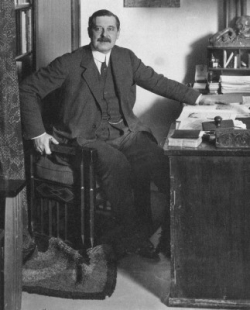

Peter Behrens (1868-1940) is today inextricably linked with the founders of modern architecture; his turbine factory in Berlin designed for AEG (Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft) has become legendary. In this company, he was employed as an artistic consultant and participated in what we would today call corporate design, designing everything from the appearance of advertising materials and stationery to the company logo, store designs, workshops, and even products.

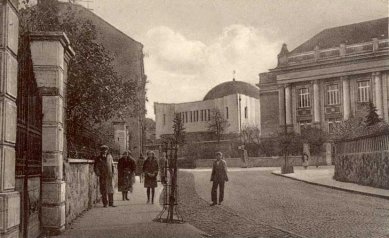

When the liberal Jewish community of neologs in Žilina announced a competition for a new synagogue design in 1928, Behrens was a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Other participants included Viennese architect Josef Hoffmann and Hungarian-born architect Lipót Baumhorn. The new neolog synagogue was built between 1929-31 according to Behrens' design. The architect had to deal with the complex terrain situation, as the irregularly shaped plot was located on a gentle slope between the post office and the bank. Behrens adeptly resolved the complications with a suitable floor plan and utilized almost the entire area of the land. He positioned the main central section of the synagogue in the widest part of the plot and connected it on the southern side with a wing for winter prayer services. He balanced the uneven terrain on the northern side with a terrace featuring an L-shaped staircase.

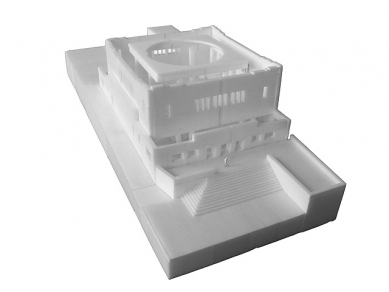

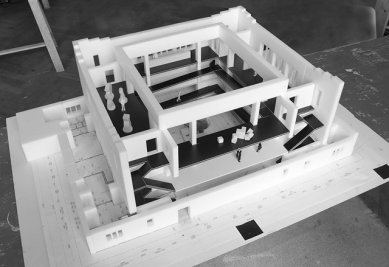

Externally, the building appears monumental yet elegant and simple. The ground floor made of rough stone masonry creates a massive base for the structure, from which arises the smoothly plastered facade of the main hall with tall, slender windows and raised corners. At first glance, the viewer is struck by the contrast of these two parts, two different materials, their structure, and colors. This division, however, is not merely aesthetic but illustrates the functional layout of the building into service and communication spaces on the ground floor and the actual prayer space. The building is topped with a reinforced concrete dome, 16 m in diameter and 17.6 m high, which was evidently part of the brief. The central hall was designed to accommodate up to 450 men, while the galleries had space for 300 women.

The synagogue served its purpose for only ten years. The deteriorating economic situation of the Jewish community and high construction costs left the building burdened with a mortgage of approximately 2 million crowns. The Jewish community, decimated by World War II, was understandably unable to repay the mortgage, and thus after the war, the synagogue was handed over to the National Committee in Žilina. It was briefly used as a storage facility and later as a concert hall; from the 1960s, it served as the representative auditorium of the University of Transport. In 1963, the synagogue was entered into the Central Register of Cultural Monuments of Slovakia. After the revolution up to the recent past, it served as a cinema hall. This tumultuous history is also related to more or less invasive construction modifications, which primarily affected the interior and roofing.

The city ultimately returned the building to the Jewish religious community, marking the beginning of a new chapter in the life of this significant Slovak monument. In 2011, the civil association Truc sphérique rented the synagogue for a symbolic rent of one euro, creating a project for its reconstruction and use. The ideological fathers of the project are Marek Adamov and Fedor Blaščák, and the author of the renovation study is architect Martin Jančok, holder of the CE.ZA.AR architectural award 2011. The aim of the reconstruction, estimated at around one million euros, is to cleanse the building of non-original parts, such as the auditorium, stage, wall cladding, and projection booth, and adjust it for a new function. The construction modifications will also reopen the view into the dome within the main hall.

The reconstructed building of the Žilina synagogue will serve as a kunsthalle, an exhibition institution without its own collection, organizing temporary exhibitions of visual art. The project authors aim to take advantage of the city’s advantageous location on the map of Central Europe, and therefore they are counting largely on foreign visitors. In addition to exhibition activities, the institution will also serve informal education and research activities. Visitors will also be able to attend club film screenings, concerts, conferences, or festivals.

If everything goes according to plan, the reconstruction should be completed in 2014. Its financing is partly from public sources and partly from private sources. Construction modifications have already begun, and the association is still seeking additional possible sponsors.

Peter Behrens (1868-1940) is today inextricably linked with the founders of modern architecture; his turbine factory in Berlin designed for AEG (Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft) has become legendary. In this company, he was employed as an artistic consultant and participated in what we would today call corporate design, designing everything from the appearance of advertising materials and stationery to the company logo, store designs, workshops, and even products.

When the liberal Jewish community of neologs in Žilina announced a competition for a new synagogue design in 1928, Behrens was a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna. Other participants included Viennese architect Josef Hoffmann and Hungarian-born architect Lipót Baumhorn. The new neolog synagogue was built between 1929-31 according to Behrens' design. The architect had to deal with the complex terrain situation, as the irregularly shaped plot was located on a gentle slope between the post office and the bank. Behrens adeptly resolved the complications with a suitable floor plan and utilized almost the entire area of the land. He positioned the main central section of the synagogue in the widest part of the plot and connected it on the southern side with a wing for winter prayer services. He balanced the uneven terrain on the northern side with a terrace featuring an L-shaped staircase.

Externally, the building appears monumental yet elegant and simple. The ground floor made of rough stone masonry creates a massive base for the structure, from which arises the smoothly plastered facade of the main hall with tall, slender windows and raised corners. At first glance, the viewer is struck by the contrast of these two parts, two different materials, their structure, and colors. This division, however, is not merely aesthetic but illustrates the functional layout of the building into service and communication spaces on the ground floor and the actual prayer space. The building is topped with a reinforced concrete dome, 16 m in diameter and 17.6 m high, which was evidently part of the brief. The central hall was designed to accommodate up to 450 men, while the galleries had space for 300 women.

The synagogue served its purpose for only ten years. The deteriorating economic situation of the Jewish community and high construction costs left the building burdened with a mortgage of approximately 2 million crowns. The Jewish community, decimated by World War II, was understandably unable to repay the mortgage, and thus after the war, the synagogue was handed over to the National Committee in Žilina. It was briefly used as a storage facility and later as a concert hall; from the 1960s, it served as the representative auditorium of the University of Transport. In 1963, the synagogue was entered into the Central Register of Cultural Monuments of Slovakia. After the revolution up to the recent past, it served as a cinema hall. This tumultuous history is also related to more or less invasive construction modifications, which primarily affected the interior and roofing.

The city ultimately returned the building to the Jewish religious community, marking the beginning of a new chapter in the life of this significant Slovak monument. In 2011, the civil association Truc sphérique rented the synagogue for a symbolic rent of one euro, creating a project for its reconstruction and use. The ideological fathers of the project are Marek Adamov and Fedor Blaščák, and the author of the renovation study is architect Martin Jančok, holder of the CE.ZA.AR architectural award 2011. The aim of the reconstruction, estimated at around one million euros, is to cleanse the building of non-original parts, such as the auditorium, stage, wall cladding, and projection booth, and adjust it for a new function. The construction modifications will also reopen the view into the dome within the main hall.

The reconstructed building of the Žilina synagogue will serve as a kunsthalle, an exhibition institution without its own collection, organizing temporary exhibitions of visual art. The project authors aim to take advantage of the city’s advantageous location on the map of Central Europe, and therefore they are counting largely on foreign visitors. In addition to exhibition activities, the institution will also serve informal education and research activities. Visitors will also be able to attend club film screenings, concerts, conferences, or festivals.

If everything goes according to plan, the reconstruction should be completed in 2014. Its financing is partly from public sources and partly from private sources. Construction modifications have already begun, and the association is still seeking additional possible sponsors.

Martina Šišková

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment