Current Architecture in Bratislava

“The identity of Bratislava is liquid and changeable. The city seems to be starting anew all the time. As one of the few European cities, it changed its name a hundred years ago. The entire twentieth century was a period of thick lines for Bratislava, and it is still constantly seeking its identity. It persists as a story of a multicultural city, which has transformed from ethnic diversity to regional diversity. Bratislava is something like a small Slovakia, where all Slovak regions meet, seasoned with a significant number of foreigners.”

As the current mayor Matúš Vallo states, Bratislava is indeed a rich mixture of life and architecture, and just like in other big cities, various layers and deposits of individual nationalities, cultures, and historical periods that Bratislava and its inhabitants have gone through are visible here. It is precisely this aspect that gives Bratislava its unique diversity and "awkwardness," making it appealing to me with its natural and effortless impression.

On the other hand, most contemporary constructions do not align with this view of mine. Developers acquiring huge plots and vast areas are generally building “multipurpose” buildings that are supposed to serve the public – but in reality, they live only off of commerce, resembling glass showcases with offices and stores, all in very similar styles and lacking a human scale. I also see a problem in the quantity of department stores in the city center; in comparison to other cities of similar size, their number is excessive, and the size of these centers is disproportionate to Bratislava. From the first built Polus (36,000 m² of retail space), it is 1.6 km to Central (39,000 m²). From Central, it is 1.6 km to the new Nivy (100,000 m²), Nivy is 1 km from Eurovea (85,000 m²). And from Eurovea, it is 2 kilometers to Aupark (60,000 m²). It would be beautiful to imagine life spilling from these containers into the surrounding streets. But the truth is that people seek out these centers and they are constantly full. They are also an immense ecological burden on the city and the exact opposite of something natural and viable, spaces primarily serving human greed and consumption. A reporter from Denník N critically but accurately writes: “I went up to the roof of the new shopping center Stanica Nivy, looking at the city from a new perspective. I was pondering what a great violence we are willing to do to the planet just to plant a few trees and shrubs on the roof of a shopping center, watering and maintaining the whole thing, while a park could simply be planted in the ground without all these problems, but then it couldn't serve as bait for a shopping center.”

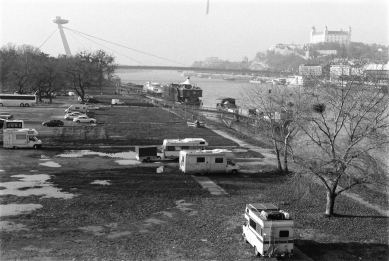

I largely share this radical view, but I sometimes let myself be swayed by convenience and shop in shopping centers too. I do not want to evaluate these complexes only from the perspective of the quality of architecture itself, but from the perspective of public spaces they offer, which are a main city-forming element that contributes to the quality of life in the city and should possess a certain softness and friendliness. I have yet to find such an atmosphere in most of these “zones,” and I think it is primarily due to their size and the enormous speed of construction. These new complexes include the current new shopping center with a bus station Nivy, the under-construction new quarter Eurovea II, and a large number of new residential complexes like Panorama City and Sky Park, which create a new Bratislava "downtown." Also, projects a few years old on the banks of the Danube, such as River Park and Zuckermandel. I am genuinely curious about the planned project Vydrica, which is set to rise at the historic site beneath Bratislava Castle and is supposed to bring life to the open streets for promenade, instead of enclosing them in a shopping mall. Among other positive examples, I would mention Pradiareň 1900 in the former Bratislava cotton mill, which is one of the few national cultural monuments in Bratislava returning to life.

There are organizations like Čierne diery dedicated to architecture, which has long been overlooked in Slovakia, from century-old factories to dilapidated spas, to icons of modern architecture. Their photographs and stories have found tens of thousands of readers and have become a motivation for visiting or revitalizing monuments in various corners of Slovakia. Čierne diery publishes reports and studies on architecture in the form of authorial books. The first book on the journey through industrial monuments across Slovakia has become an independent bestseller and an inspiration for tourism development. Another well-known Bratislava brand is Bratiska, which also seeks to make various neighborhoods of Bratislava visible and promote them through minimalist textile design to raise residents' awareness.

Bratislava has many good and quality organizations and institutions, whether municipal, private, or non-profit, that help steer Bratislava in the right direction. An important one is the Metropolitan Institute of Bratislava (MIB), which is a conceptual institute in the field of architecture, urban planning, participation, and strategic planning. It consists of a team of experts in architecture, urbanism, and city development, which plans growth and development to improve both the quality of life and the quality of public space. MIB aims to support quality architecture and functional solutions in urban projects and plans that reflect the needs of Bratislava residents, considering social and climate changes. MIB is a contributory organization of the capital city.

Thanks to the international Muniss competition I participated in with Slovak students four years ago, I was able to delve deeper into the topic of visual smog on Obchodná Street and its surrounding area. Also, thanks to this competition, I got involved in the Živé námestie project, located at Námestí SNP, Námestí Nežnej revolúcie, and Kamenné námestie in Bratislava, where a team of architects wants to create a unified public space. “Živé námestie will become a public living room, where a strong historical legacy merges with the modern face of Bratislava” is the slogan on the project's website. As a strong attractor in the city center, I perceive the building of the Old Market Hall at Námestí Nežnej revolúcie, which has been running several businesses for several years and hosts many projects and festivals positively affecting the public.

Matúš Vallo, Plan Bratislava

As the current mayor Matúš Vallo states, Bratislava is indeed a rich mixture of life and architecture, and just like in other big cities, various layers and deposits of individual nationalities, cultures, and historical periods that Bratislava and its inhabitants have gone through are visible here. It is precisely this aspect that gives Bratislava its unique diversity and "awkwardness," making it appealing to me with its natural and effortless impression.

On the other hand, most contemporary constructions do not align with this view of mine. Developers acquiring huge plots and vast areas are generally building “multipurpose” buildings that are supposed to serve the public – but in reality, they live only off of commerce, resembling glass showcases with offices and stores, all in very similar styles and lacking a human scale. I also see a problem in the quantity of department stores in the city center; in comparison to other cities of similar size, their number is excessive, and the size of these centers is disproportionate to Bratislava. From the first built Polus (36,000 m² of retail space), it is 1.6 km to Central (39,000 m²). From Central, it is 1.6 km to the new Nivy (100,000 m²), Nivy is 1 km from Eurovea (85,000 m²). And from Eurovea, it is 2 kilometers to Aupark (60,000 m²). It would be beautiful to imagine life spilling from these containers into the surrounding streets. But the truth is that people seek out these centers and they are constantly full. They are also an immense ecological burden on the city and the exact opposite of something natural and viable, spaces primarily serving human greed and consumption. A reporter from Denník N critically but accurately writes: “I went up to the roof of the new shopping center Stanica Nivy, looking at the city from a new perspective. I was pondering what a great violence we are willing to do to the planet just to plant a few trees and shrubs on the roof of a shopping center, watering and maintaining the whole thing, while a park could simply be planted in the ground without all these problems, but then it couldn't serve as bait for a shopping center.”

I largely share this radical view, but I sometimes let myself be swayed by convenience and shop in shopping centers too. I do not want to evaluate these complexes only from the perspective of the quality of architecture itself, but from the perspective of public spaces they offer, which are a main city-forming element that contributes to the quality of life in the city and should possess a certain softness and friendliness. I have yet to find such an atmosphere in most of these “zones,” and I think it is primarily due to their size and the enormous speed of construction. These new complexes include the current new shopping center with a bus station Nivy, the under-construction new quarter Eurovea II, and a large number of new residential complexes like Panorama City and Sky Park, which create a new Bratislava "downtown." Also, projects a few years old on the banks of the Danube, such as River Park and Zuckermandel. I am genuinely curious about the planned project Vydrica, which is set to rise at the historic site beneath Bratislava Castle and is supposed to bring life to the open streets for promenade, instead of enclosing them in a shopping mall. Among other positive examples, I would mention Pradiareň 1900 in the former Bratislava cotton mill, which is one of the few national cultural monuments in Bratislava returning to life.

There are organizations like Čierne diery dedicated to architecture, which has long been overlooked in Slovakia, from century-old factories to dilapidated spas, to icons of modern architecture. Their photographs and stories have found tens of thousands of readers and have become a motivation for visiting or revitalizing monuments in various corners of Slovakia. Čierne diery publishes reports and studies on architecture in the form of authorial books. The first book on the journey through industrial monuments across Slovakia has become an independent bestseller and an inspiration for tourism development. Another well-known Bratislava brand is Bratiska, which also seeks to make various neighborhoods of Bratislava visible and promote them through minimalist textile design to raise residents' awareness.

Bratislava has many good and quality organizations and institutions, whether municipal, private, or non-profit, that help steer Bratislava in the right direction. An important one is the Metropolitan Institute of Bratislava (MIB), which is a conceptual institute in the field of architecture, urban planning, participation, and strategic planning. It consists of a team of experts in architecture, urbanism, and city development, which plans growth and development to improve both the quality of life and the quality of public space. MIB aims to support quality architecture and functional solutions in urban projects and plans that reflect the needs of Bratislava residents, considering social and climate changes. MIB is a contributory organization of the capital city.

Thanks to the international Muniss competition I participated in with Slovak students four years ago, I was able to delve deeper into the topic of visual smog on Obchodná Street and its surrounding area. Also, thanks to this competition, I got involved in the Živé námestie project, located at Námestí SNP, Námestí Nežnej revolúcie, and Kamenné námestie in Bratislava, where a team of architects wants to create a unified public space. “Živé námestie will become a public living room, where a strong historical legacy merges with the modern face of Bratislava” is the slogan on the project's website. As a strong attractor in the city center, I perceive the building of the Old Market Hall at Námestí Nežnej revolúcie, which has been running several businesses for several years and hosts many projects and festivals positively affecting the public.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment