Engelsmann Villa in Brno

1931–1932

In the 1930s, when functionalism already fully dominated the architectural creation in Brno, a conservative private villa was being built on Hlinky Street by the almost forgotten Brno industrialist and art collector Felix Engelsmann. His villa contrasts even more with the grand market palaces of the modern exhibition area, which had been built only a few years earlier in the opposite position.

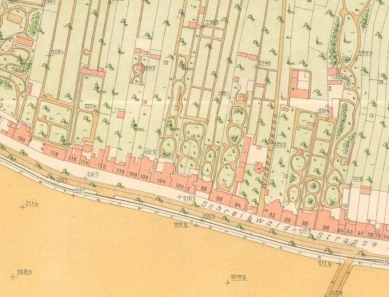

Hlinky Street began to emerge at the foot of the Yellow Hill as a natural connector between Old Brno and the bridge over the Svratka River in the Pisárky Valley, from where one could further head toward Kohoutovice, Jundrov, and the settlement of Kamenný mlýn. The suitable location, along with the southern orientation of the Yellow Hill slope, created conditions for the cultivation of vineyards in this area. On Hlinky, thus, there arose wine houses and facilities with sunken wine cellars. Even in 1924, in connection with changes in ownership at Hlinky 108, we can read that: “Moritz Schnabel sold his house No. 108 in Lehmstätte, including the vineyard and land [...]” In fact, remnants of these buildings, including wine cellars, still remain in the street, though in a fragmented form.

A fundamental transformation in the character of the street and its development began after the mid-19th century when the Pisárky Valley became a popular excursion spot, and Brno entrepreneurs and politicians began to seek this location for the construction of their summer residences of suburban and urban types. The entire street can be divided into two parts, where the first part, leading from Mendlovo Square to the turn-off into Lipová Street, concentrates continuous street development. In the second part, approximately from this turn-off to the bridge across the Svratka, solitary villa buildings predominately stand in gardens.

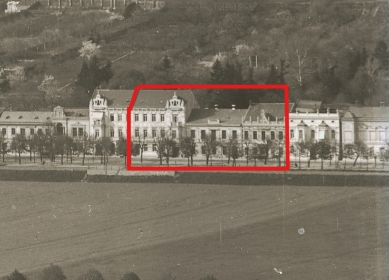

This state of the street is very well illustrated by a panoramic photograph of Hlinka from 1911, originating from the collections of the Museum of the City of Brno. The photographic triptych depicts the empty space of the future exhibition area and Yellow Hill, which, with few exceptions, still lacks the now-characteristic buildings and is instead planted with fruit trees and vineyards. If we focus on Hlinky Street itself, we can observe a fairly diverse spectrum of architecture in the part with continuous street development, ranging from small wine houses to representative rental housing (for example, the double house of Eugen Škarda, Hlinky 46 and 46a from 1898), up to villa and palace buildings, among which the palace with a prominent neo-Renaissance facade at Hlinky 86 (the palace of Johanna and Jonas Karpeles from 1897) stands out the most. Near the turn-off to today's Lipová Street, solitary villas begin, of which the first, at Hlinky 132, is the villa of military tailor Ludvik Dukát. The last, although incompletely captured by the photographer, is the modernist villa of industrialist Hugo Hecht located at Hlinky 142b, built here between 1910-1911 according to the project of Leopold Bauer. Upon closer inspection of the address Hlinky 108-112 that we are tracking, we can even see a trio of houses that preceded the construction of Felix Engelsmann's villa.

The life of Felix Engelsmann, especially his wartime and post-war life, has not yet been significantly documented, and therefore this article now attempts to briefly introduce this personality. From available sources, we know that Felix Engelsmann was born on June 3, 1885, in Brno. His father Gustav (1853-1929) was born in Gyöngyös, Hungary, and his mother Friderika (1860-1933) in Nový Bydžov. Gustav Engelsmann was a wool merchant who, in 1885, became a public partner in the wool goods manufacturing firm of Heinrich Brück, located at Cejl 32 in Brno. With the arrival of the new partner, the firm immediately changed its name to Brück & Engelsmann, a name that not only survived the death of Heinrich Brück in 1905 but was still used by the company in Western Europe during World War II, until it was dissolved in 1980.

The eldest child of Gustav and Friderika Engelsmann was Felix himself, followed by two daughters, Stephania (April 1, 1887) and the youngest, Ilsa (October 19, 1900). From 1897 to 1900, Felix Engelsmann attended the State Real Gymnasium in Brno, and afterward, he was an exceptional student (intern) at the vocational school associated with the weaving school. After his studies, in 1907 and 1908, he was initially a procurator in his father's company Brück & Engelsmann; however, in 1913, at just 28 years old, he became a public partner in the firm. In the yearbook of the Brno Weaving School from 1911, Felix Engelsmann, along with figures such as Viktor and Hugo Hecht, Walter Löw-Beer, Walter Neumark, Ernest Stiassni, and Benno Tugendhat, is mentioned as a member of the festival committee for the anniversary celebration that took place on December 6th in the ballroom of the German House.

During this time, the entire family likely lived in their house at what is now Kpt. Jaroš Street 35. Archive documents reveal that Felix Engelsmann, prior to the construction of his villa on Hlinky, had two other residences, namely French Street 1 (now Milady Horákové 1 or 1a) and Legionaires' Street 19 (now Kpt. Jaroš 19). The nature of Engelsmann's relationship to the mentioned addresses is not yet clear.

At the end of 1917, specifically on December 13, 1917, Felix Engelsmann married Vienna native Olga Stein, for whom archival sources mention two different birth years, 1887 and 1889. Her second name is also problematic, as it is referred to both as Olga Engelsmann Ballin and Gattin.

A fundamental change in the life of Felix Engelsmann and the family firm came with the creation of Czechoslovakia and the following two decades. In 1918, Gustav Engelsmann left the company at the age of sixty-five. Conversely, his son Felix firmly established himself in the business, as did Hugo Hanak (1880-1932) and later his son Richard Hanak (1908-?). The firm thus started to be listed as: “Brück & Engelsmann, public partners Hugo Hanak and Felix Engelsmann. Each one signs independently. Manufacturing and sale of sheep wool goods. Zeile 32. T. 611 - A/I./66.” Hugo Hanak, also an influential entrepreneur in the wool industry, had been married since 1906 to Felix Engelsmann's younger sister, Stephania. One of their three children was Richard Hanak. The Hanak family then owned the adjacent property at Kpt. Jaroš Street 33.

The connection between the Engelsmann and Hanak families naturally strengthened their economic and social standing, which was regularly criticized, particularly by communists and socialists, as for example in Neužil's Novels from Brno from 1936: “Where are the capitalists? How many are there? Löw-Beer, Kohn, Weiss, Stiassni, Hanak, Otto Kuhn, Redlich, and a few more. You could count them on the fingers of one hand, those who build millions and prosperity from the labor of thousands.” Despite this socialist criticism, the firm Brück & Engelsmann employed several hundred employees, aimed to export its products abroad, including to the United States, and had further expansion tendencies. Somewhere during the 1920s, Brück & Engelsmann acquired the area of the former Offermann factory on Trnita. We learn about this, among other things, from an article in Lidové noviny from 1927 when the area caught fire: “Recently, the well-known Brno textile company Brück & Engelsmann purchased the entire enterprise, intending to transform the factory into manufacturing fine fabrics from carded yarn.” Despite the crisis at the beginning of the 1930s and the necessity to lay off and remove several employees from production, in 1932 the firm purchased the adjacent area at Cejl 24/26 from Aug. Märisch from further extension. This year is especially important in Felix Engelsmann's life since he also completes the construction of his villa on Hlinky.

However, Engelsmann began to show interest in the location on Hlinky more than a decade earlier. First, in 1921, he purchased a house with a garden at Hlinky 112 from Paul Hayek for 380,000 crowns. Then in 1924 and 1925, he also bought the land and the house at Hlinky 108 from Moritz Schnabel for 230,000 crowns, and finally in 1929, he bought the last building at Hlinky 110 from Cyril Wladika. This gradual acquisition of houses suggests a well-considered intention of Engelsmann to build a new and generous residence located on the parcel of three older houses, which could successfully compete with the older villa constructions of other Brno art-loving industrialists in the street. Naturally, these buildings were also an eyesore to the socialists of the time. For example, in 1923, in the social democrats' paper Rovnost, besides the biting criticism of capitalism, with a latent touch of anti-Semitism, interesting details regarding the approximate value of these buildings and further construction circumstances are mentioned. This time, Engelsmann himself is mentioned: “Let us just look at how the manufacturers, wholesalers, bank directors, and all those similar lords thrive. We have seen the harm they caused during the most severe economic crisis that our republic has recently suffered. It suffices to notice the provocative splendor of the manufacturers' villas in the Pisárky district. Manufacturer Löw-Beer is building a luxurious villa at Hlinky No. 132 at a cost of 10 million crowns for 4 people (It is interesting that he entrusts the execution to Germans from the Reich; it does not bother him about the unemployment of domestic firms). The same manufacturer's family owns villa No. 86 in the same street with 12 rooms, inhabited by 2 people; villa No. 6 with 10 rooms, which is half empty, reserved for some Jew from Vienna, villa No. 104 with 15 rooms for 2 people, and finally villa No. 116 with 12 rooms also for 2 people. Industrialist Engelsmann arranged for his wife a villa at Hlinky No. 112 at a cost of 8 million crowns. [...]” In this article, the noteworthy point is the mention of the execution of August Löw-Beer's villa at Hlinky 132/134, entrusted to German firms, and probably also to a thus far unknown designer of the building. This fact could be a useful lead in searching for the author of the Engelsmann villa, which stands out from the traditional production of architects operating in Brno.

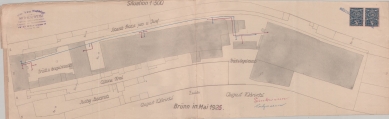

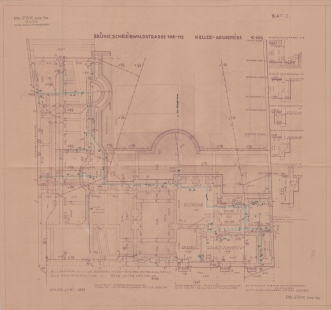

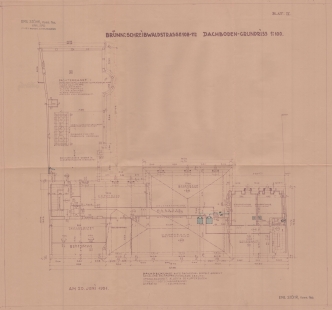

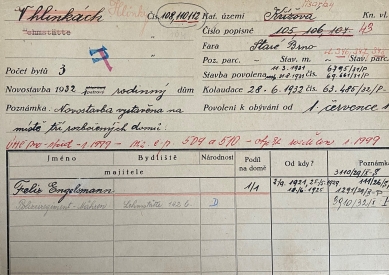

After Engelsmann had succeeded in purchasing three houses with plots on Hlinky between 1921 and 1929, he likely commissioned the project for construction in 1930. On February 18, 1931, we can read in the Lidové noviny that: “F. Engelsmann was permitted to demolish the houses 108, 110, and the second floor of house 112 on Hlinky.” In the archive of Brno Waterworks and Sewage, there is a collection of plans with plumbing work provided by the company Emil Stöhr from Karlovy Vary, dated to June 1931. The same company also provided plumbing work in the Stiassni villa and the Esplanade café. In quite detailed documentation for the Engelsmann villa, which includes, among other things, a description of the materials used, only the German language is used. For illustration of the subsequent progress of construction, we can also combine records from the property card stored at the Brno City Hall. This card enables us, apart from the sentence that: “New construction built on the site of three demolished houses.”, to obtain a more detailed report about the building permit that was issued to Engelsmann on March 11, 1931, or August 31, 1931, and that the construction was approved on June 28, 1932. Thus, in 1932, Felix Engelsmann joins the company of other wealthy and influential Brno entrepreneurs, especially in the field of textiles, like the Offermann, Hecht, Löw-Beer, or Bloch families, which were united, among other things, by art collecting.

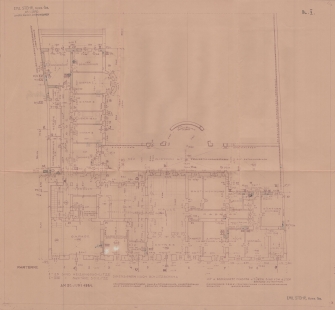

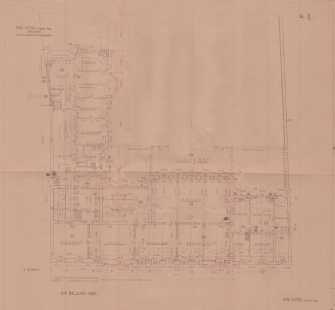

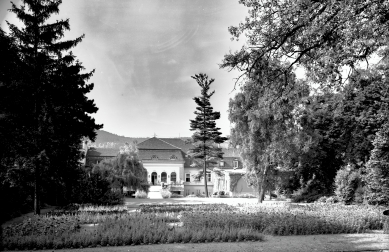

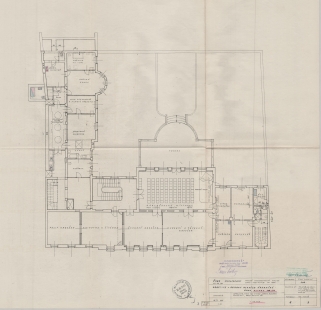

The Engelsmann villa was built on a floor plan in the shape of an L, emphasizing the execution of the representative facade of the building toward the street. The facade is divided into three masses, as if referring to the trio of original buildings that the villa replaced. The central mass of the building towers, accentuated by the proportions of the window openings and the mansard roof. Compared to the street facade, the wing facing the garden is designed significantly more soberly. Based on preserved construction documentation, we can also divide the internal arrangement of the villa into three functional units. One part is designated for service and the operational background of the villa, which is located in the right section of the building. Further, there are predominant spaces for social and representative functions, located along the entire length of the first floor of the villa, and finally, the private part with bedrooms and facilities for the owners, which the architect placed in the wing facing the garden. Access to the building is through the main entrance portal in the central part of the building, behind which is a spacious vestibule. From there, on the right, there was access to the guest apartment and also to the service part, where the driver’s apartment and the gardener’s room were located. This section of the building not only has its own service staircase but also a separate entrance from the street, so as not to disrupt the private and social life of its owners.

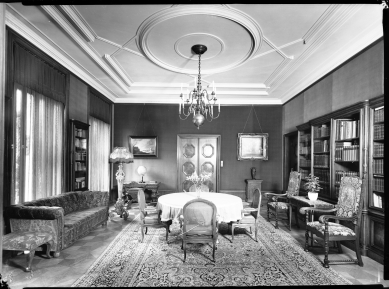

To the left of the entrance hall, access leads to a generous staircase, which leads into the social rooms on the floor. This part is dominated by the main hall with a fireplace and a specific stucco finish on the ceiling. Toward the street, the rooms of the dining room, gentlemen's room, salon, and music salon are then lined up. It is worth mentioning the now-preserved stained-glass windows in the former dining room of the villa. At least two of these stained glass pieces refer to the Netherlands and Dutch visual art (one stained-glass with a figure of Jan Swart van Groningen), which undoubtedly symbolizes Felix Engelsmann's relationship with the old Dutch masters.

The private part of the villa with living rooms, located in the wing facing the garden, is accessible from the first floor, or also through its own private staircase for the owners. In this part, there were two bedrooms with separate bathrooms and a breakfast room. This wing of the building is equipped with a flat roof with a walkable terrace and skylights, which illuminate the corridor between the owners’ bedrooms. Some of the preserved technical details, such as window fittings marked “Patent Nikolaus” and “DRGM” (Deutsches Reichsgebrauchsmuster), testify to the German provenance of these products.

In the Brno Technical Museum, a series of unique photographs is preserved, allowing us to peek into the interior of the villa. At least two of these photographs, capturing the street facade of the villa, were taken shortly after March 15, 1939, when the Gestapo began to show interest in the property and its owners. In the photographs, branches of trees lining Hlinky Street, are still visible, and also the still intact entrance portal of the villa. Notably, there is also a Tatra 75 car captured in one of the photographs standing in front of the villa. This is likely a car seized by the Gestapo that belonged to Engelsmann. Other images were taken a bit later, probably already in the summer of 1939. In the third photograph of the street facade, we can see that the consoles at the entrance portal have been removed, their place replaced by the Nazi eagle. As mentioned, after the occupation of Brno by the Nazis, the property was seized by the Gestapo, which is also noted in the land registry. During 1939 or at the latest at the beginning of 1940, the Gestapo then donated the property free of charge to the German Police (Deutsche Schutzpolizei in Brünn, Polizeiregiment Mähren). Despite the fact that the collection of photographs from the Technical Museum was taken only after the occupation, these images allow a glimpse into the interior of the villa and its furnishings, which undoubtedly refer—except for a few exceptions of Nazi symbolism—to the original owner of the building, Felix Engelsmann. As can be seen, the villa's interior was furnished with antique furniture and valuable artworks, especially visual art, and the architectural tone of the entire building leans heavily on Felix Engelsmann's extensive art collection.

His collecting passion already had a family tradition, and he could thus expand his father's collection. In 1929, Felix Engelsmann took part in the Amsterdam auction of Otto Kuhn's art gallery, where he purchased at least one piece of artwork. Alongside him, the auction of Kuhn's collection included Julius Drucker, Hans Löffler, Heinrich Perschak, Heinrich Plaček, Alfred Stiassni. All of those mentioned were united, among other things, by their membership in the Moravian Artistic Association. One of the many paintings in Felix Engelsmann's art collection is also mentioned by Emil Filla in a letter to Kutal from: “Dear Doctor Kutal, the owner’s address of Chittussi's painting in Brno is: Felix Engelsmann, large industrialist, at Hlinky 110, Brno. Please write to him to see if he has a decent photograph or if he would allow you to take one for the Sources. The painting was bought from Dr. H. Feigl, from whom I have his address. Best regards, Emil Filla.” Whether a photograph of Chittussi's painting has ultimately been obtained is unclear. It is certain, however, that by the end of the 1930s, Felix Engelsmann must have sensed the intensifying threat as a Jewish citizen. Already in 1938, Engelsmann began to be interested in the Taylor Hill Mills complex in Huddersfield, England. In the same year, probably still under the impression that freedom could be maintained in Czechoslovakia, he donated 250,000 crowns to the state in a fund for the defense of the republic. A few months later, however, all hopes for the Jewish population were extinguished.

We can gain an idea of his sudden and surely dramatic departure abroad from the text written by Franz Lerch, the Nazi-appointed administrator of the Brück & Engelsmann company, on November 16, 1940, to the Reich Commissioner for the management of enemy property in Prague: “I discovered that Jew Felix Engelsmann, accompanied by his wife, left for Vienna on the afternoon of March 14, 1939, with the driver of his car. Although at the factory he said he was going on an 8-day business trip to Switzerland, his departure was sudden, almost hurried. After a very short stay in Vienna, he had himself driven to the train station and left for Zurich. [...] His destination was Huddersfield, England. As I know, two shareholders lent the name of a well-known world company on September 21, 1938, for 10 years for an annual fee of 300 English pounds. A nephew of the partner, Jew Richard Hanák, who also fled, had previously been employed there as a general director, and Felix Engelsmann started to work at this company, Brück und Engelsmann Ltd., in April 1939.”

Thus, while the Nazis in Brno performed the liquidation of the firm Brück & Engelsmann and merged the company under Vereinigte Schafwollwarenfabriken A.G. Brünn, the firm operated under its original name and under the leadership of both partners even during the war, managed from British Huddersfield. It was in this industrial city that Engelsmann settled with his wife Olga and nephew Richard Hanak. Even here, Engelsmann did not hide his inclination towards historicism and conservative architecture. For his needs, he purchased the Bankfield residence, a neo-Gothic building from the 1860s, originally built by wool trader and industrialist James Priestley. However, the building was demolished in 2007.

During the war years, Engelsmann still identified with Czechoslovakia. He was likely the most significant member of the British Czechoslovak Friendship Club, founded there in 1943. While during the war, the firm employed 250 people in Britain, its former factory complex in Brno sustained significant damage during the Allied air raid on Brno on November 20, 1944. Both apartment buildings at Kpt. Jaroš Street 33 and 35 were also severely damaged.

Interestingly, after the war, Engelsmann showed no interest in his property in Brno. Only one letter is known from July 23, 1947, in which he addressed the Moravian Museum, to whose collections the collection of artworks from the villa on Hlinky had passed during the war. In the letter, Engelsmann requests the return of one of his paintings: “In your museum is a painting by Pettenkofen /"annual market"/ which belongs to me and was once stolen by Germans from my house in Brno. I believe the painting is known to you, for if you wish, I can send you a copy of the painting and also prove that I purchased the painting many years ago. However, I think it is known to you that the painting was my property, and therefore no proof of purchase is needed. I would like to decide about this painting and notify you of to whom you should hand it over. Please confirm this letter today. Sincerely, Felix Engelsmann.” A few days later, on July 29, 1947, the then-director of the museum provides a brief response to Engelsmann: “Dear Sir, in response to your inquiry from July 23 this year, we inform you that the painting "Annual Market" by Pettenkofen was handed over to the regional museum during the war and is stored in the warehouse of the provincial gallery. Director”

This very brief correspondence gives a glimpse into the post-war situation in Czechoslovakia and the relatively challenging efforts of Jewish residents to claim their former property here. Until 1961, works of art from Engelsmann's collection were stored in the Moravian Gallery. Of the total of 19 works confiscated during the war, 14 works have been preserved to this day, which are now in the collections of the Moravian Gallery.

The corporate area on Cejl and also the villa on Hlinky had a similar fate. In 1946, the firm's area was incorporated under the Moravian-Silesian Woolen Company, and national administration was also imposed on the Engelsmann villa. In the same year, a plan to provide the villa to the Union of Friends of the USSR emerged, as evidenced by an article from January 3, 1946, in the paper of the Czech Social Democratic Party Čin, describing the visit of the Soviet ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Valerian Alexandrovich Zorin, to Brno: “As a symbol of the struggle for freedom and work, Ambassador Zorin mentioned the reconstruction of Stalingrad, so that the damages caused by the war could be restored in the nearest future and Stalingrad could again live the life of a Russian industrial metropolis. At the end of his speech, Ambassador Zorin proclaimed eternal friendship between the nations of Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union and wished the whole nation much success in the new year. Enthusiastically greeted, ambassador Zorin then went to inspect villa No. 108 on Hlinky Street, which is still owned by the national fund and which the worthy MNV is to put into use for the Union of Friends of the USSR.” However, this plan was probably ultimately not realized, as already in 1946, the office of the Land National Council, specifically the Office for Trades, moved into the villa, and in 1947, also the Regional Study and Planning Institute. Apart from the original documentation from 1931, documentation from 1949 is also stored in the archive of Brno Waterworks and Sewage, which considers the adaptation of the former Engelsmann villa, along with adjacent buildings Hlinky 112a, 114, and 116, for the needs of the Home of Young Shock Workers. The builder here is listed as Preparatory Committee for Building “Home of Young Shock Workers” Brno Hlinky. In 1955, the ownership rights to the villa passed to the Ministry of Labor, and in 1958 to the First Brno Machine Factory, plant Klement Gottwald, which likely relates to the development of engineering fairs and the necessity to have representative spaces in close proximity to the exhibition area.

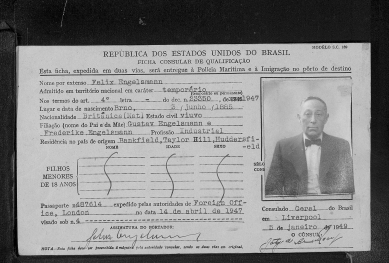

We learn about the end of Felix Engelsmann's life only from British sources. He gained British citizenship on March 19, 1947. His wife Olga died in Britain in 1945. After her death, Felix Engelsmann married Berta Neumann, a native of Schöllkrippen, Germany (born December 17, 1897), who had been living in Britain since 1939. As a British citizen, he received a visa for Brazil at the Brazilian consulate in Liverpool on January 5, 1949. From this document comes the only known portrait photograph of Felix Engelsmann to date. A year later, in 1950, the couple traveled to New York. During this stay, however, Engelsmann suffered a stroke, and shortly after returning to Britain, Felix Engelsmann died at the age of 64. In his will, he left his wife £5,000, and the rest of the estate was inherited by his nephew Richard Hanak.

His former villa on Hlinky is currently in private ownership, and the authorship of the building is the subject of further research. As mentioned above, the author of the object could be one of the conservative architects who designed buildings for demanding clients in Czechoslovakia, such as architects Max Spielmann or Paul Brockardt. It is also not excluded that it could have been an Austrian or German architect. Just a few years before the construction of the Engelsmann villa, Gusti Löw-Beer completed the reconstruction of her villa at Hlinky 104 in 1929. The architect of this almost neighboring villa was the Viennese architect Rudolf Bredl, and it is noteworthy that both buildings feature numerous technical similarities and utilize identical products.

The current photographs of the villa were taken between August and October 2022.

This contribution is dedicated to Felix Engelsmann and all the Jewish residents of the city who have been forgotten.

Acknowledgements:

Petra Dovola, Palace Hlinky

Margaret Woodcock, Huddersfield & District Family History Society

Naděžda Urbánková, Technical Museum in Brno

Petr Houzar, Archive of the City of Brno

Silvie Klimešová, Brno Waterworks and Sewage, a.s.

Lenka Kudělková, Museum of the City of Brno

Sources:

Archive of the City of Brno

Brno Waterworks and Sewage, a.s.

Bundesarchiv

Geni.com

Huddersfield & District Family History Society

Internet Encyclopedia of the History of Brno

Cadastral Office for the South Moravian Region, Brno-Country Cadastral Office

Brno City Hall, Department of Internal Affairs Moravian Regional Library

Moravian Gallery

Moravian State Archive

Museum of the City of Brno

National Heritage Institute, Regional Specialized Workplace Brno

Technical Museum in Brno

Literature:

Directory of Greater Brno. 28th year - 28. Jahrgang. 1930. [Brünn]: Friedr. Irrgang Verlag,

Brünner Morgenpost. September 21, 1921, vol. 56, p. 3.

Brünner Morgenpost. August 9, 1924, vol. 59, p. 2.

Brünner Morgenpost. July 7, 1925, vol. 60, p. 2.

Čin: paper of the Czech Social Democratic Party for the liberation of the part of Moravia. January 3, 1946, vol. 2, no. 2, p. 3.

Lidové noviny. February 8, 1930, vol. 38, no. 70, p. 16.

Lidové noviny. February 18, 1931, vol. 39, no. 88, p. 4.

Lidové noviny. March 10, 1933, vol. 41, no. 126, p. 14.

Lidové noviny. October 1, 1937, vol. 35, no. 496, p. 1.

Lidové noviny. June 21, 1938, vol. 46, no. 309, p. 4.

Národní obroda: central organ of the Czechoslovak People's Party. 1946, vol. 2, no. 229, p. 109.

NEUŽIL, František. The Country in the Draft: A Novel from Brno. Moravian Circle of Writers in Brno, 1936.

Rovnost: paper of the Czech social democrats. August 23, 1923, vol. 39, no. 231, p. 4.

SLAVÍČEK, Lubomír. “To Myself, Art to Friends”: Chapters from the History of Collecting in Bohemia and Moravia 1650 - 1939. Society for Professional Literature, 2007, pp. 207-220.

SLAVÍČEK, Lubomír. Irene Beran and the Others: Brno Art Collectors of German Nationality Before 1939. In: Alis Volat Propriis: Collection of Contributions for the Life Jubilee of Ludmila Sulitková. Brno, 2016, pp. 576-595.

Word of the Nation: Organ of the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party. November 18, 1947, vol. 3, no. 268, p. 5.

SMUTNÝ, Bohumír. Brno Entrepreneurs and Their Enterprises: 1764-1948: Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurs and Their Families. Brno: Statutory City of Brno, Archive of the City of Brno, 2012.

Hlinky Street began to emerge at the foot of the Yellow Hill as a natural connector between Old Brno and the bridge over the Svratka River in the Pisárky Valley, from where one could further head toward Kohoutovice, Jundrov, and the settlement of Kamenný mlýn. The suitable location, along with the southern orientation of the Yellow Hill slope, created conditions for the cultivation of vineyards in this area. On Hlinky, thus, there arose wine houses and facilities with sunken wine cellars. Even in 1924, in connection with changes in ownership at Hlinky 108, we can read that: “Moritz Schnabel sold his house No. 108 in Lehmstätte, including the vineyard and land [...]” In fact, remnants of these buildings, including wine cellars, still remain in the street, though in a fragmented form.

A fundamental transformation in the character of the street and its development began after the mid-19th century when the Pisárky Valley became a popular excursion spot, and Brno entrepreneurs and politicians began to seek this location for the construction of their summer residences of suburban and urban types. The entire street can be divided into two parts, where the first part, leading from Mendlovo Square to the turn-off into Lipová Street, concentrates continuous street development. In the second part, approximately from this turn-off to the bridge across the Svratka, solitary villa buildings predominately stand in gardens.

This state of the street is very well illustrated by a panoramic photograph of Hlinka from 1911, originating from the collections of the Museum of the City of Brno. The photographic triptych depicts the empty space of the future exhibition area and Yellow Hill, which, with few exceptions, still lacks the now-characteristic buildings and is instead planted with fruit trees and vineyards. If we focus on Hlinky Street itself, we can observe a fairly diverse spectrum of architecture in the part with continuous street development, ranging from small wine houses to representative rental housing (for example, the double house of Eugen Škarda, Hlinky 46 and 46a from 1898), up to villa and palace buildings, among which the palace with a prominent neo-Renaissance facade at Hlinky 86 (the palace of Johanna and Jonas Karpeles from 1897) stands out the most. Near the turn-off to today's Lipová Street, solitary villas begin, of which the first, at Hlinky 132, is the villa of military tailor Ludvik Dukát. The last, although incompletely captured by the photographer, is the modernist villa of industrialist Hugo Hecht located at Hlinky 142b, built here between 1910-1911 according to the project of Leopold Bauer. Upon closer inspection of the address Hlinky 108-112 that we are tracking, we can even see a trio of houses that preceded the construction of Felix Engelsmann's villa.

The life of Felix Engelsmann, especially his wartime and post-war life, has not yet been significantly documented, and therefore this article now attempts to briefly introduce this personality. From available sources, we know that Felix Engelsmann was born on June 3, 1885, in Brno. His father Gustav (1853-1929) was born in Gyöngyös, Hungary, and his mother Friderika (1860-1933) in Nový Bydžov. Gustav Engelsmann was a wool merchant who, in 1885, became a public partner in the wool goods manufacturing firm of Heinrich Brück, located at Cejl 32 in Brno. With the arrival of the new partner, the firm immediately changed its name to Brück & Engelsmann, a name that not only survived the death of Heinrich Brück in 1905 but was still used by the company in Western Europe during World War II, until it was dissolved in 1980.

The eldest child of Gustav and Friderika Engelsmann was Felix himself, followed by two daughters, Stephania (April 1, 1887) and the youngest, Ilsa (October 19, 1900). From 1897 to 1900, Felix Engelsmann attended the State Real Gymnasium in Brno, and afterward, he was an exceptional student (intern) at the vocational school associated with the weaving school. After his studies, in 1907 and 1908, he was initially a procurator in his father's company Brück & Engelsmann; however, in 1913, at just 28 years old, he became a public partner in the firm. In the yearbook of the Brno Weaving School from 1911, Felix Engelsmann, along with figures such as Viktor and Hugo Hecht, Walter Löw-Beer, Walter Neumark, Ernest Stiassni, and Benno Tugendhat, is mentioned as a member of the festival committee for the anniversary celebration that took place on December 6th in the ballroom of the German House.

During this time, the entire family likely lived in their house at what is now Kpt. Jaroš Street 35. Archive documents reveal that Felix Engelsmann, prior to the construction of his villa on Hlinky, had two other residences, namely French Street 1 (now Milady Horákové 1 or 1a) and Legionaires' Street 19 (now Kpt. Jaroš 19). The nature of Engelsmann's relationship to the mentioned addresses is not yet clear.

At the end of 1917, specifically on December 13, 1917, Felix Engelsmann married Vienna native Olga Stein, for whom archival sources mention two different birth years, 1887 and 1889. Her second name is also problematic, as it is referred to both as Olga Engelsmann Ballin and Gattin.

A fundamental change in the life of Felix Engelsmann and the family firm came with the creation of Czechoslovakia and the following two decades. In 1918, Gustav Engelsmann left the company at the age of sixty-five. Conversely, his son Felix firmly established himself in the business, as did Hugo Hanak (1880-1932) and later his son Richard Hanak (1908-?). The firm thus started to be listed as: “Brück & Engelsmann, public partners Hugo Hanak and Felix Engelsmann. Each one signs independently. Manufacturing and sale of sheep wool goods. Zeile 32. T. 611 - A/I./66.” Hugo Hanak, also an influential entrepreneur in the wool industry, had been married since 1906 to Felix Engelsmann's younger sister, Stephania. One of their three children was Richard Hanak. The Hanak family then owned the adjacent property at Kpt. Jaroš Street 33.

The connection between the Engelsmann and Hanak families naturally strengthened their economic and social standing, which was regularly criticized, particularly by communists and socialists, as for example in Neužil's Novels from Brno from 1936: “Where are the capitalists? How many are there? Löw-Beer, Kohn, Weiss, Stiassni, Hanak, Otto Kuhn, Redlich, and a few more. You could count them on the fingers of one hand, those who build millions and prosperity from the labor of thousands.” Despite this socialist criticism, the firm Brück & Engelsmann employed several hundred employees, aimed to export its products abroad, including to the United States, and had further expansion tendencies. Somewhere during the 1920s, Brück & Engelsmann acquired the area of the former Offermann factory on Trnita. We learn about this, among other things, from an article in Lidové noviny from 1927 when the area caught fire: “Recently, the well-known Brno textile company Brück & Engelsmann purchased the entire enterprise, intending to transform the factory into manufacturing fine fabrics from carded yarn.” Despite the crisis at the beginning of the 1930s and the necessity to lay off and remove several employees from production, in 1932 the firm purchased the adjacent area at Cejl 24/26 from Aug. Märisch from further extension. This year is especially important in Felix Engelsmann's life since he also completes the construction of his villa on Hlinky.

However, Engelsmann began to show interest in the location on Hlinky more than a decade earlier. First, in 1921, he purchased a house with a garden at Hlinky 112 from Paul Hayek for 380,000 crowns. Then in 1924 and 1925, he also bought the land and the house at Hlinky 108 from Moritz Schnabel for 230,000 crowns, and finally in 1929, he bought the last building at Hlinky 110 from Cyril Wladika. This gradual acquisition of houses suggests a well-considered intention of Engelsmann to build a new and generous residence located on the parcel of three older houses, which could successfully compete with the older villa constructions of other Brno art-loving industrialists in the street. Naturally, these buildings were also an eyesore to the socialists of the time. For example, in 1923, in the social democrats' paper Rovnost, besides the biting criticism of capitalism, with a latent touch of anti-Semitism, interesting details regarding the approximate value of these buildings and further construction circumstances are mentioned. This time, Engelsmann himself is mentioned: “Let us just look at how the manufacturers, wholesalers, bank directors, and all those similar lords thrive. We have seen the harm they caused during the most severe economic crisis that our republic has recently suffered. It suffices to notice the provocative splendor of the manufacturers' villas in the Pisárky district. Manufacturer Löw-Beer is building a luxurious villa at Hlinky No. 132 at a cost of 10 million crowns for 4 people (It is interesting that he entrusts the execution to Germans from the Reich; it does not bother him about the unemployment of domestic firms). The same manufacturer's family owns villa No. 86 in the same street with 12 rooms, inhabited by 2 people; villa No. 6 with 10 rooms, which is half empty, reserved for some Jew from Vienna, villa No. 104 with 15 rooms for 2 people, and finally villa No. 116 with 12 rooms also for 2 people. Industrialist Engelsmann arranged for his wife a villa at Hlinky No. 112 at a cost of 8 million crowns. [...]” In this article, the noteworthy point is the mention of the execution of August Löw-Beer's villa at Hlinky 132/134, entrusted to German firms, and probably also to a thus far unknown designer of the building. This fact could be a useful lead in searching for the author of the Engelsmann villa, which stands out from the traditional production of architects operating in Brno.

After Engelsmann had succeeded in purchasing three houses with plots on Hlinky between 1921 and 1929, he likely commissioned the project for construction in 1930. On February 18, 1931, we can read in the Lidové noviny that: “F. Engelsmann was permitted to demolish the houses 108, 110, and the second floor of house 112 on Hlinky.” In the archive of Brno Waterworks and Sewage, there is a collection of plans with plumbing work provided by the company Emil Stöhr from Karlovy Vary, dated to June 1931. The same company also provided plumbing work in the Stiassni villa and the Esplanade café. In quite detailed documentation for the Engelsmann villa, which includes, among other things, a description of the materials used, only the German language is used. For illustration of the subsequent progress of construction, we can also combine records from the property card stored at the Brno City Hall. This card enables us, apart from the sentence that: “New construction built on the site of three demolished houses.”, to obtain a more detailed report about the building permit that was issued to Engelsmann on March 11, 1931, or August 31, 1931, and that the construction was approved on June 28, 1932. Thus, in 1932, Felix Engelsmann joins the company of other wealthy and influential Brno entrepreneurs, especially in the field of textiles, like the Offermann, Hecht, Löw-Beer, or Bloch families, which were united, among other things, by art collecting.

The Engelsmann villa was built on a floor plan in the shape of an L, emphasizing the execution of the representative facade of the building toward the street. The facade is divided into three masses, as if referring to the trio of original buildings that the villa replaced. The central mass of the building towers, accentuated by the proportions of the window openings and the mansard roof. Compared to the street facade, the wing facing the garden is designed significantly more soberly. Based on preserved construction documentation, we can also divide the internal arrangement of the villa into three functional units. One part is designated for service and the operational background of the villa, which is located in the right section of the building. Further, there are predominant spaces for social and representative functions, located along the entire length of the first floor of the villa, and finally, the private part with bedrooms and facilities for the owners, which the architect placed in the wing facing the garden. Access to the building is through the main entrance portal in the central part of the building, behind which is a spacious vestibule. From there, on the right, there was access to the guest apartment and also to the service part, where the driver’s apartment and the gardener’s room were located. This section of the building not only has its own service staircase but also a separate entrance from the street, so as not to disrupt the private and social life of its owners.

To the left of the entrance hall, access leads to a generous staircase, which leads into the social rooms on the floor. This part is dominated by the main hall with a fireplace and a specific stucco finish on the ceiling. Toward the street, the rooms of the dining room, gentlemen's room, salon, and music salon are then lined up. It is worth mentioning the now-preserved stained-glass windows in the former dining room of the villa. At least two of these stained glass pieces refer to the Netherlands and Dutch visual art (one stained-glass with a figure of Jan Swart van Groningen), which undoubtedly symbolizes Felix Engelsmann's relationship with the old Dutch masters.

The private part of the villa with living rooms, located in the wing facing the garden, is accessible from the first floor, or also through its own private staircase for the owners. In this part, there were two bedrooms with separate bathrooms and a breakfast room. This wing of the building is equipped with a flat roof with a walkable terrace and skylights, which illuminate the corridor between the owners’ bedrooms. Some of the preserved technical details, such as window fittings marked “Patent Nikolaus” and “DRGM” (Deutsches Reichsgebrauchsmuster), testify to the German provenance of these products.

In the Brno Technical Museum, a series of unique photographs is preserved, allowing us to peek into the interior of the villa. At least two of these photographs, capturing the street facade of the villa, were taken shortly after March 15, 1939, when the Gestapo began to show interest in the property and its owners. In the photographs, branches of trees lining Hlinky Street, are still visible, and also the still intact entrance portal of the villa. Notably, there is also a Tatra 75 car captured in one of the photographs standing in front of the villa. This is likely a car seized by the Gestapo that belonged to Engelsmann. Other images were taken a bit later, probably already in the summer of 1939. In the third photograph of the street facade, we can see that the consoles at the entrance portal have been removed, their place replaced by the Nazi eagle. As mentioned, after the occupation of Brno by the Nazis, the property was seized by the Gestapo, which is also noted in the land registry. During 1939 or at the latest at the beginning of 1940, the Gestapo then donated the property free of charge to the German Police (Deutsche Schutzpolizei in Brünn, Polizeiregiment Mähren). Despite the fact that the collection of photographs from the Technical Museum was taken only after the occupation, these images allow a glimpse into the interior of the villa and its furnishings, which undoubtedly refer—except for a few exceptions of Nazi symbolism—to the original owner of the building, Felix Engelsmann. As can be seen, the villa's interior was furnished with antique furniture and valuable artworks, especially visual art, and the architectural tone of the entire building leans heavily on Felix Engelsmann's extensive art collection.

His collecting passion already had a family tradition, and he could thus expand his father's collection. In 1929, Felix Engelsmann took part in the Amsterdam auction of Otto Kuhn's art gallery, where he purchased at least one piece of artwork. Alongside him, the auction of Kuhn's collection included Julius Drucker, Hans Löffler, Heinrich Perschak, Heinrich Plaček, Alfred Stiassni. All of those mentioned were united, among other things, by their membership in the Moravian Artistic Association. One of the many paintings in Felix Engelsmann's art collection is also mentioned by Emil Filla in a letter to Kutal from: “Dear Doctor Kutal, the owner’s address of Chittussi's painting in Brno is: Felix Engelsmann, large industrialist, at Hlinky 110, Brno. Please write to him to see if he has a decent photograph or if he would allow you to take one for the Sources. The painting was bought from Dr. H. Feigl, from whom I have his address. Best regards, Emil Filla.” Whether a photograph of Chittussi's painting has ultimately been obtained is unclear. It is certain, however, that by the end of the 1930s, Felix Engelsmann must have sensed the intensifying threat as a Jewish citizen. Already in 1938, Engelsmann began to be interested in the Taylor Hill Mills complex in Huddersfield, England. In the same year, probably still under the impression that freedom could be maintained in Czechoslovakia, he donated 250,000 crowns to the state in a fund for the defense of the republic. A few months later, however, all hopes for the Jewish population were extinguished.

We can gain an idea of his sudden and surely dramatic departure abroad from the text written by Franz Lerch, the Nazi-appointed administrator of the Brück & Engelsmann company, on November 16, 1940, to the Reich Commissioner for the management of enemy property in Prague: “I discovered that Jew Felix Engelsmann, accompanied by his wife, left for Vienna on the afternoon of March 14, 1939, with the driver of his car. Although at the factory he said he was going on an 8-day business trip to Switzerland, his departure was sudden, almost hurried. After a very short stay in Vienna, he had himself driven to the train station and left for Zurich. [...] His destination was Huddersfield, England. As I know, two shareholders lent the name of a well-known world company on September 21, 1938, for 10 years for an annual fee of 300 English pounds. A nephew of the partner, Jew Richard Hanák, who also fled, had previously been employed there as a general director, and Felix Engelsmann started to work at this company, Brück und Engelsmann Ltd., in April 1939.”

Thus, while the Nazis in Brno performed the liquidation of the firm Brück & Engelsmann and merged the company under Vereinigte Schafwollwarenfabriken A.G. Brünn, the firm operated under its original name and under the leadership of both partners even during the war, managed from British Huddersfield. It was in this industrial city that Engelsmann settled with his wife Olga and nephew Richard Hanak. Even here, Engelsmann did not hide his inclination towards historicism and conservative architecture. For his needs, he purchased the Bankfield residence, a neo-Gothic building from the 1860s, originally built by wool trader and industrialist James Priestley. However, the building was demolished in 2007.

During the war years, Engelsmann still identified with Czechoslovakia. He was likely the most significant member of the British Czechoslovak Friendship Club, founded there in 1943. While during the war, the firm employed 250 people in Britain, its former factory complex in Brno sustained significant damage during the Allied air raid on Brno on November 20, 1944. Both apartment buildings at Kpt. Jaroš Street 33 and 35 were also severely damaged.

Interestingly, after the war, Engelsmann showed no interest in his property in Brno. Only one letter is known from July 23, 1947, in which he addressed the Moravian Museum, to whose collections the collection of artworks from the villa on Hlinky had passed during the war. In the letter, Engelsmann requests the return of one of his paintings: “In your museum is a painting by Pettenkofen /"annual market"/ which belongs to me and was once stolen by Germans from my house in Brno. I believe the painting is known to you, for if you wish, I can send you a copy of the painting and also prove that I purchased the painting many years ago. However, I think it is known to you that the painting was my property, and therefore no proof of purchase is needed. I would like to decide about this painting and notify you of to whom you should hand it over. Please confirm this letter today. Sincerely, Felix Engelsmann.” A few days later, on July 29, 1947, the then-director of the museum provides a brief response to Engelsmann: “Dear Sir, in response to your inquiry from July 23 this year, we inform you that the painting "Annual Market" by Pettenkofen was handed over to the regional museum during the war and is stored in the warehouse of the provincial gallery. Director”

This very brief correspondence gives a glimpse into the post-war situation in Czechoslovakia and the relatively challenging efforts of Jewish residents to claim their former property here. Until 1961, works of art from Engelsmann's collection were stored in the Moravian Gallery. Of the total of 19 works confiscated during the war, 14 works have been preserved to this day, which are now in the collections of the Moravian Gallery.

The corporate area on Cejl and also the villa on Hlinky had a similar fate. In 1946, the firm's area was incorporated under the Moravian-Silesian Woolen Company, and national administration was also imposed on the Engelsmann villa. In the same year, a plan to provide the villa to the Union of Friends of the USSR emerged, as evidenced by an article from January 3, 1946, in the paper of the Czech Social Democratic Party Čin, describing the visit of the Soviet ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Valerian Alexandrovich Zorin, to Brno: “As a symbol of the struggle for freedom and work, Ambassador Zorin mentioned the reconstruction of Stalingrad, so that the damages caused by the war could be restored in the nearest future and Stalingrad could again live the life of a Russian industrial metropolis. At the end of his speech, Ambassador Zorin proclaimed eternal friendship between the nations of Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union and wished the whole nation much success in the new year. Enthusiastically greeted, ambassador Zorin then went to inspect villa No. 108 on Hlinky Street, which is still owned by the national fund and which the worthy MNV is to put into use for the Union of Friends of the USSR.” However, this plan was probably ultimately not realized, as already in 1946, the office of the Land National Council, specifically the Office for Trades, moved into the villa, and in 1947, also the Regional Study and Planning Institute. Apart from the original documentation from 1931, documentation from 1949 is also stored in the archive of Brno Waterworks and Sewage, which considers the adaptation of the former Engelsmann villa, along with adjacent buildings Hlinky 112a, 114, and 116, for the needs of the Home of Young Shock Workers. The builder here is listed as Preparatory Committee for Building “Home of Young Shock Workers” Brno Hlinky. In 1955, the ownership rights to the villa passed to the Ministry of Labor, and in 1958 to the First Brno Machine Factory, plant Klement Gottwald, which likely relates to the development of engineering fairs and the necessity to have representative spaces in close proximity to the exhibition area.

We learn about the end of Felix Engelsmann's life only from British sources. He gained British citizenship on March 19, 1947. His wife Olga died in Britain in 1945. After her death, Felix Engelsmann married Berta Neumann, a native of Schöllkrippen, Germany (born December 17, 1897), who had been living in Britain since 1939. As a British citizen, he received a visa for Brazil at the Brazilian consulate in Liverpool on January 5, 1949. From this document comes the only known portrait photograph of Felix Engelsmann to date. A year later, in 1950, the couple traveled to New York. During this stay, however, Engelsmann suffered a stroke, and shortly after returning to Britain, Felix Engelsmann died at the age of 64. In his will, he left his wife £5,000, and the rest of the estate was inherited by his nephew Richard Hanak.

His former villa on Hlinky is currently in private ownership, and the authorship of the building is the subject of further research. As mentioned above, the author of the object could be one of the conservative architects who designed buildings for demanding clients in Czechoslovakia, such as architects Max Spielmann or Paul Brockardt. It is also not excluded that it could have been an Austrian or German architect. Just a few years before the construction of the Engelsmann villa, Gusti Löw-Beer completed the reconstruction of her villa at Hlinky 104 in 1929. The architect of this almost neighboring villa was the Viennese architect Rudolf Bredl, and it is noteworthy that both buildings feature numerous technical similarities and utilize identical products.

The current photographs of the villa were taken between August and October 2022.

This contribution is dedicated to Felix Engelsmann and all the Jewish residents of the city who have been forgotten.

Mgr. Michal Doležel

Acknowledgements:

Petra Dovola, Palace Hlinky

Margaret Woodcock, Huddersfield & District Family History Society

Naděžda Urbánková, Technical Museum in Brno

Petr Houzar, Archive of the City of Brno

Silvie Klimešová, Brno Waterworks and Sewage, a.s.

Lenka Kudělková, Museum of the City of Brno

Sources:

Archive of the City of Brno

Brno Waterworks and Sewage, a.s.

Bundesarchiv

Geni.com

Huddersfield & District Family History Society

Internet Encyclopedia of the History of Brno

Cadastral Office for the South Moravian Region, Brno-Country Cadastral Office

Brno City Hall, Department of Internal Affairs Moravian Regional Library

Moravian Gallery

Moravian State Archive

Museum of the City of Brno

National Heritage Institute, Regional Specialized Workplace Brno

Technical Museum in Brno

Literature:

Directory of Greater Brno. 28th year - 28. Jahrgang. 1930. [Brünn]: Friedr. Irrgang Verlag,

Brünner Morgenpost. September 21, 1921, vol. 56, p. 3.

Brünner Morgenpost. August 9, 1924, vol. 59, p. 2.

Brünner Morgenpost. July 7, 1925, vol. 60, p. 2.

Čin: paper of the Czech Social Democratic Party for the liberation of the part of Moravia. January 3, 1946, vol. 2, no. 2, p. 3.

Lidové noviny. February 8, 1930, vol. 38, no. 70, p. 16.

Lidové noviny. February 18, 1931, vol. 39, no. 88, p. 4.

Lidové noviny. March 10, 1933, vol. 41, no. 126, p. 14.

Lidové noviny. October 1, 1937, vol. 35, no. 496, p. 1.

Lidové noviny. June 21, 1938, vol. 46, no. 309, p. 4.

Národní obroda: central organ of the Czechoslovak People's Party. 1946, vol. 2, no. 229, p. 109.

NEUŽIL, František. The Country in the Draft: A Novel from Brno. Moravian Circle of Writers in Brno, 1936.

Rovnost: paper of the Czech social democrats. August 23, 1923, vol. 39, no. 231, p. 4.

SLAVÍČEK, Lubomír. “To Myself, Art to Friends”: Chapters from the History of Collecting in Bohemia and Moravia 1650 - 1939. Society for Professional Literature, 2007, pp. 207-220.

SLAVÍČEK, Lubomír. Irene Beran and the Others: Brno Art Collectors of German Nationality Before 1939. In: Alis Volat Propriis: Collection of Contributions for the Life Jubilee of Ludmila Sulitková. Brno, 2016, pp. 576-595.

Word of the Nation: Organ of the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party. November 18, 1947, vol. 3, no. 268, p. 5.

SMUTNÝ, Bohumír. Brno Entrepreneurs and Their Enterprises: 1764-1948: Encyclopedia of Entrepreneurs and Their Families. Brno: Statutory City of Brno, Archive of the City of Brno, 2012.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment