Can a young Czech office composed of a trio of architects and an assistant achieve interesting projects, including international ones? FAM Architekti demonstrate that yes. Can a young Czech office composed of a trio of architects and an assistant achieve interesting projects, including international ones? FAM Architekti demonstrate that yes.Not only about how they acquired an international partner and what advantages such cooperation brings them, we talked with Jan Horký and Pavel Nasadil in their studio located on the ground floor of an industrial building in Prague's Holešovice. Although they work on projects for London, Accra, and Lagos in addition to Czech contracts, they are currently not considering inviting additional colleagues. As they themselves say: “Sometimes we have waves where we think about expanding the team, but in the end, it always works out. The size of the office is very important. Once it grows, a certain hierarchy and administrative systems must be established...” Your office operates in a partnership with a British architectural practice. Can you clarify how this - certainly not a common working scheme in the Czech environment - came about and what advantages it brings? Pavel Nasadil: Our collaboration, of course, has its history. After high school in the Czech Republic, I can say I studied at another school in Britain. For my diploma work in the subject of Art, I chose the residential buildings of Richard Rogers. At that time, Rogers's public buildings, such as Lloyd's Bank and the Pompidou Centre, were well known, but the topic of residential buildings was not well mapped yet. I searched libraries and discovered that the architects Feilden + Mawson not only had their library but even their librarian. They didn’t have the book I was looking for, but they kindly ordered it from the RIBA library in London and lent it to me for three weeks. By the way, I visited all of Rogers's houses and met the architect's mother for whom one of them was designed. I then gradually started visiting their studio to observe their work, and later I went to the office to work as a student. After finishing at the Czech Technical University in Prague, I completed my internship there. So, the history is long. It naturally emerged from this relationship that we would continue to collaborate. We founded FAM Architekti in 2005 with their financial assistance. Can the form of your current collaboration be defined more precisely? PN: We mainly work on projects that are starting and are at the competition, study, or as they call it, feasibility study stages. Some projects are carried through to the spatial permit stage – like the Green Park Metro Station, while others end before they start. One or two will be built without our direct follow-up collaboration. Such is the case with the reconstruction of the Middlesex Guildhall in London into the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom.

PN: They celebrated their fiftieth anniversary last year, and they have three studios: the headquarters is in Norwich, where I just studied and where the initial contact was made, the second is located in London, and the smallest is in Cambridge. The firm has about sixty employees in total. What has this collaboration given you the most? PN: Thanks to our cooperation with the British office, we have, for example, a very well-managed order management system. Backtracking documents or clearly archiving materials... Jan Horký: For instance, when Tomáš creates something in a project where I work less, I can quickly find his drawing or document on the computer. PN: Or, if we are working on a large project like the hospital in Ealing, we have a system that very well records the trail of when we sent what drawing or document to whom. It is not complicated, but when the office operates this way, its organization is much simpler. That’s why we sometimes hesitate about employing students... But to return to the question. The benefits lie chiefly in two areas: collaborating with a foreign partner ensures a steady stream of work – which is a key topic particularly in today’s times, associated with a certain financial security and thus the possibility of implementing projects in the Czech Republic that we could not devote ourselves to for so long or with such care without such support. The second area is, of course, the fact that thanks to collaboration with the Brits, we gain access to work we would not have been able to as a small starting Czech office. Moreover, the projects coming from England are usually pleasant tasks – public contracts that offer us a chance to touch upon various typological themes – whether they are transport structures or very complicated assignments from the public sector such as judicial buildings, laboratories, or educational facilities... So, tasks that you wouldn’t access in the Czech Republic... PN: ...and in England, without help, neither. JH: When judicial buildings were mentioned, I would add that they represent an interesting experience with that typology for us. The English judicial system is based on a completely different principle than the Czech one. In Britain, it is very important to keep different operations separate, and the designs must balance so that certain user groups do not meet at all. The building is then interwoven with a number of staircases and corridors that are independent of one another. We would never access such a commission here, and it is possible that such a demanding typological task does not even exist here.

PN: In Britain, the path to a commission is more complex. The investor, namely the state, is very aware of how challenging a public building task is. They are thus divided into groups called frameworks. The mentioned judicial buildings have their own framework group. A framework group then includes a certain range of offices that meet the qualifications to design a specific building. Must they meet certain qualifications here? PN: They must be on the list. That’s why it is so complicated to obtain a contract. But how do they get on the list? PN: They apply and must meet certain criteria: primarily practical experience with the selected kind of buildings. The framework also works such that you can become either a design architect – i.e., design the building, or a technical advisor to the investor for that area, who oversees and challenges the architectural team working on the commission. Feilden + Mawson even has qualifications for both. And isn’t such a system discriminatory for younger offices? JH: Perhaps we are getting to the difference between the Czechs and the Brits. In 2007, for instance, we applied for a competition for Údolní 53 announced by the Brno University of Technology for the construction of a new university campus. Nothing prevented us from participating in this competition as a young three-person studio, and we ultimately won the competition. PN: Just so it doesn’t come across that there are no architectural competitions in England. On the contrary. There are more competitions, and there’s always a guarantee that the public building will go through a competition: whether it’s an open competition like we know here, i.e., public, anonymous, international, which is posted on the European bulletin or it’s a selection procedure – a invited competition where the investor approaches architects from the mentioned framework area. Selection is guaranteed all the time. In our regard, there is chaos. How public contracts are commissioned – if they even go through a competition – I don’t know. Of course, it is harder to fight for a contract in Britain, but if you obtain one, it is deservedly so.

PN: It concerns the St. Bernard’s psychiatric hospital, which is reportedly the largest facility of its kind in Europe, or at least it was until the early 20th century. The building represents a beautiful example of period, let’s say textbook mechanical typology of the 19th century, which was later added to at various times. The facility still functions as a facility for mentally ill individuals, mostly with the undercurrent of a certain criminal act. The objective of the hospital is to move to spaces that will correspond to modern treatment methods because the original building is today absolutely inadequate from this perspective: both technically, disposition-wise, and in character – patients were previously bound with chains in small cells. However, in order for new buildings to be constructed, the old ones must be sold. Our task is to create apartments in the layout of the old asylum. This is the largest project we have ever worked on. We are only a part of a large team, with a project manager – which can be several people – the main architects dealing with the master plan of the area and new buildings for the hospital, then us, who are responsible for historical buildings and conversion to residential purposes, as well as landscape architects, engineers, developers, and even a selected contractor who assesses the construction in terms of financial viability. So, it is a very complex project in terms of coordination. JH: For me, it is interesting that the investor first obtains a spatial permit that evaluates the construction. In England, it is very difficult to obtain a building permit for historic monuments – and this object is protected at the second level. If the building already has a permit, its value in the market significantly increases... With what concept do you want to enter the area? PN: The feasibility study is done, and it has been shown that the layout is not ideal for residential purposes. The entire building based on a symmetrical floor plan creates a two-wing structure with a wide corridor. It seems that the layout will have to be changed rather forcefully into staircase sections. On the other hand, it has turned out that the long facades with numerous windows and several extensions are the building’s advantages. Originally, we wanted to remove all the later additions from the object and actually expand it into a certain unified profile. However, demolishing the appendices has proven disadvantageous for residential purposes. The assignment thus presents a problem of preservation, construction, and morality. A church is also located on the site, which is integrated into the hospital buildings. It stands at the center of events and is very important in the overall urban concept. Our task is to transform this church into residential purpose as well – a task that is unthinkable from the perspective of Czech heritage preservation. The tradition of conversions in England is so deep that even a change of function is perceived as a natural evolution of a building – once a building is no longer used, heritage preservation is willing to accept radical change. However, with some things, we do not fully identify... Are you suggesting that you have an ethical problem with the demand to convert a sacred building into apartments? PN: A little bit. JH: You have to come to terms with the assignment. Initially, we approached the object as a church, but gradually we understood that we had to look at it as a house. As a volume that has walls, windows, a roof, and into which apartments are inserted. We had to let go of the spiritual content. PN: Just yesterday, I returned from London, where, among other things, we talked about the church. The place of crossing the nave is, in our opinion, unsuitable for residential purposes - a beautiful large, dark space that deserves to remain whole. It is central to the building and should be left open rather than divided and sliced. However, this certainly does not bring any benefit or financial return to the investor. Even the developer can tolerate our opinion, but not the investor. The question arose, why don’t we just demolish the church. But that surely isn’t even theoretically possible in the case of a protected monument? PN: It is not. But at the meeting, we had to justify why we want to preserve it. Precisely for the reasons mentioned above, especially the church’s role in the urban center of the entire complex. AFRICA

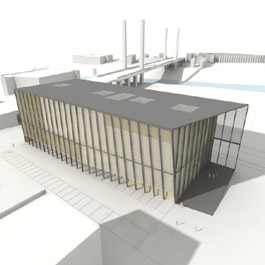

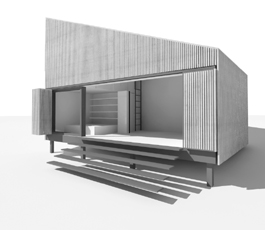

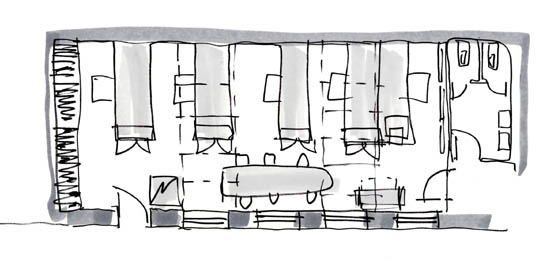

PN: Both projects are very similar. There is a transportation system that has already been tried, for example, in South America in Bogotá or in Brazilian Curitiba. It is called Bus Rapid Transit. It is a system of public bus transport that is conducted in separately defined lanes. It is being introduced into the largest and most problematic cities in the world. The projects in Lagos and Accra are pilot projects because this system has not yet been tried in Africa. JH: It can be said that it is a sort of cheaper version of the metro, whereby transportation is segregated, yet it can also be built with much lower financial investments on the existing surface communication network. The main arteries of the city are tested, and either they are wide enough to accommodate the required bus lane, or in some areas, they are expanded. Did buses in large African cities represent the only solution? Or did you consider other types of transport? I mean trams or even the metro... JH: We got to the project at a stage when it had already been decided. Of course, there were a whole range of analyses and studies before the considerations about types of transport that examined the area in terms of sociological, ecological, and primarily economic aspects. Buses are, however, always the cheapest option. Their routes, frequency, connections to other types of transport, and so forth are then examined. Criteria also include coverage for the poorest inhabitants, practical possibility to introduce traffic lanes, efficiency, economic cost, and return on investment... Personally, I believe that a dedicated traffic lane is the solution for those cities and areas. PN: The chosen optimal solution is further elaborated concerning the location and number of stops, types, positions of transfer nodes, terminals, and depots. Only after this phase did we, as architects, enter the project to propose the visual and structural form of these transport buildings. In this stage, issues of climate and location must also be addressed and respected in the design.

PN: Lagos, as well as the whole of Nigeria, is a wealthy city by African standards - primarily due to oil extraction. In the 1970s, extensive transport infrastructure was built in Lagos from its profits, on which this bus system is based. Regarding construction materials, we could afford to use steel. However, in Accra, or Ghana, there are no steel mills, so we had to use local building materials, such as fired clay bricks and prefabricated concrete elements for the main structural components. This is again a certain building tradition that exists in Ghana. Climate influences were very similar in both projects, as both cities lie on the coast of the ocean very close together, practically only an hour's flight apart. Did you collaborate on the projects with local experts? PN: We, of course, visited the site: once in Lagos, three times in Accra. There is always a local architectural office and project manager who acts as a coordinator. By the way, how did you perceive the issue that you – of course, said with a certain exaggeration – “white” Europeans design a transport system for local “black” inhabitants? Does it reflect some hidden prolongation of the colonial era? Including the transfer of cultural patterns... PN: I think this comment is irrelevant in today’s global world. The question does not strike me as one from the twenty-first century. JH: The world is shrinking. PN: It’s not as if in Africa, “whites” are working on a project that is completely foreign to the region. On the contrary, the project adapts as much as possible to the place; it’s not a colonial import. One way to achieve this is through collaboration with local artists. In Ghana, we visited very significant painters and conceptual creators with international reputations: for example, Kofi Setordji and Akwele Suma Glory. We also sought inspiration in Kente textiles and large ceremonial umbrellas, typical of Ghana.

PN: In Africa, of course, many people cannot read or write. The manner of marking stops goes through some graphic symbol or collaboration with an artist. In the design of the stops, we incorporated walls that serve as a platform for visual communication and can be processed universally. JH: Each stop will be painted differently so that people can remember it. Thus, it is a concept somewhat different from the usual European approach of unified shelters distinguished only by signs with their names. And in Nigeria? PN: In Lagos, we approached the task by designing the stops to be oversized in terms of height and expression. The metropolis faces many layers of various constructions, temporary metal boxes, and clay dwellings, and it is visually quite chaotic. We wanted the icon of the bus system to be easily recognizable. That’s why we significantly oversized the height of the bus stop compared to, for example, Prague’s public transport. JH: For me, it was an interesting experience that transportation arteries accumulate life. There is trading around them or even directly on them; along them, people live. The artery is essentially the main social space in the city. Squares and other public spaces in our European spirit do not exist in the city. The artery is therefore a very significant public building. Unlike Prague, where it is perceived as something essential for the operation of the city, however very hard to add anything to, and with great reluctance does human life approach it... PN: Paradoxically, the most challenging topic that the sociologist from our Lagos team dealt with was the sensitive relocation of traders who illegally trade along the road. The goal was to prevent social tension. Therefore, all these people need to be financially compensated, even though they have no official ownership rights to the land. For example, if the bus lane is expanded, a bulldozer cannot just come and destroy the livelihoods of hundreds of people. By the way, the traffic jams actually help the traders: because of them, they concentrate around the traffic and, conversely, their presence slows the traffic down further – it’s a complex intertwined problem.

PN: When I went to Accra for work, I always had a designated driver or we hailed a taxi. But I, of course, took public transport to try it out. Currently, there are three options in the city: the cheapest are large buses belonging to larger companies, then there are the so-called danfos – minibuses that depart only when full and are owned by small private owners, and then there are taxis that only the middle class can afford. And do you have any specific experience from Africa related to public transport? JH: While we were students, we traveled with Pavel for fun as backpackers. In Ethiopia, we took a large bus to Lalibela, which is a relatively well-known complex of Christian temples carved into the rock. At that time, we chose the cheapest mode of transport – and the bus drove so slowly that you could buy things from the window during the journey. Especially in the hills. A boy runs by and casually sells you bananas... In the end, the engine overheated, and we had to walk. One hundred and twenty kilometers, which you consider insignificant in Europe, suddenly becomes a whole day’s journey. Distance is entirely relative. CZECH REPUBLIC Finally, let’s return home. You have been working for a while on the project for the central square in Dobříš, which you won in a public architectural competition in 2007... JH: Pavel lived in Dobříš for some time, and I come from Příbram, which is a neighboring town. We won and obtained the commission. It was a new experience for us because it involved designing a public space – a square. We collaborated with traffic engineers and other specialists, contemplating how the city should function – and in the end, the design became almost a regulatory plan for the center. We solved the whole center traffic-wise, and the solution also grew into the surrounding streets because the square cannot be separated from the urban organism. The defense of the project before the public at the Dobříš cultural center was also completely new for us...

PN: We didn’t worry too much about them. JH: It is very complex because the project is intended for the center of Dobříš and should belong to everyone. Thus, various, often conflicting interests collide: businesspeople want it so that anyone can park in front of their pizzeria, while elderly women demand benches and bushes... An architect must transcend the interests and ensure that the result does not turn out like a cake made by a dog and a cat. At what stage is the project currently? In the previous conversation, you hinted that it has somewhat stalled... JH: The project is complicated primarily because there are two investors: the city and the Central Bohemian Region, which owns the secondary-class road passing through the square. Without coordination between the two, the project cannot be completed. In the autumn of last year, the regional council elections were held, and as you know, the balance of power changed, with the ČSSD entering leadership, which has completely different priorities than the previous council. PN: Work on the main original assignment has stalled. However, we found a space that we are still addressing – Komenského náměstí. We obtained a building permit for it, and the city will be applying for subsidies with our collaboration. Just like in the conversations with your colleagues, we again encounter the problem of the inability to advocate for any longer-term vision amidst changing political representations. Do you believe that the original scope of work in Dobříš will be successfully implemented? PN: Anything can happen. The negation of the previous political representation’s efforts has unfortunately become somewhat automatic in our political environment. JH: Construction is a long-term process. The mayor of Dobříš, Jaroslav Melša, is genuinely trying to do more for the city than just keep it running. We support him, but his situation is difficult...

JH: I cannot talk about cottages in general. When we focus on a project, we concentrate on a specific place. We do not study general theories, such as Czech cottage theory. Our client owns an inadequate cottage at Máchovo Lake. The condition of the authorities is that renovations cannot increase the built area – which significantly impacts the project. PN: But in a positive sense. It is good that we have some constraints. JH: By having restrictions, you don't ask yourself many questions. Due to the small area, we tried to include only the essentials into the cottage. In the end, there is one living room and a small bathroom. We eliminated the anteroom, corridors, and everything else that appears in residential spaces intended for permanent living. PN: But after all, the charm of recreational housing lies precisely in the fact that many things fall away. Moreover, such a solution allows for better integration of the interior with the surroundings and a more intimate contact with the lake – because the cottage is three meters from the shore. The client is an avid sailor, has a boat anchored at Máchovo Lake and will be entering the building from the water. He will leave his car on the opposite shore and sail to the cottage... Constraints help us. Every limitation can be turned into an advantage. Moreover, it simplifies our work. When a person has too much freedom, they can drown in it. Thank you for the interview. Kateřina Lopatová

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

|