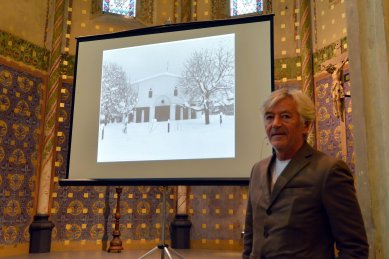

The Gallery of Contemporary Art in České Budějovice this week opened an exhibition presenting the drawings of Zurich architect Peter Märkli. On the occasion of the introductory lecture at the Students' Church of the Holy Family and the opening of the exhibition Drawings in the House of Art of the City of České Budějovice, archiweb.cz had the opportunity to conduct an interview with this unique Swiss creator on Wednesday, October 11, 2017.