Peter Stec: "I feel like a New Yorker now, and at the same time like a European."

|

On his CV, he has schools such as Die Angewandte (Vienna) and Princeton (USA), and collaborations with personalities like Greg Lynn, Zaha Hadid, Wolf Prix, Peter Eisenman, and others. Peter Eisenman invited him to his studio right after his diploma presentation at Princeton. He is definitely not a comfortable person and is never completely satisfied with anything. This trait does not allow him to stop on his journey between Vienna, New York, Basel, or London. Perhaps it all started somewhere in childhood when he spent his early school years in Algeria. We managed to catch up with him shortly after he arrived on the European continent during a short stopover in Bratislava. We talked about schools, cities, and theories.

What were your first steps in Vienna?

I transferred from the Bratislava Technical University to TU Wien in ’97. There, I worked on projects with Anton Schweighofer and Karl Chu. I had never heard of Karl before, but I immediately realized how close it might be to me. At that time, he was already exploring design through algorithms, which has always fascinated me.

But after a year, you lost interest in TU Wien?

I was lucky; the professors at TU paid a lot of attention to me. However, it's a large school, and it's not easy to get noticed there. I worked in a group with a Prix student, who had TU as just a bonus, and she showed me Angewandte. I began to take an interest in that school, realizing it was more personal, and then I transferred. The entrance exams are held in October, and if you are accepted, you start the following week.

You actually rotated through all the studios at Angewandte?

Yes, although it wasn't a rule. You were supposed to go through the entire five-year program in one studio. It might have been a disadvantage for me not to delve deeply into specific problems and visions in individual classes, but it suited me. I don't want to be too strict of a follower. Many told me later that they would also like to try it - but for that, you had to first "get expelled" and then retake the entrance exams. I experienced entrance exams with Prix, with Zaha, and then with Greg, and not everyone is in the mood for that. At least back then, it was not easy to go directly from one studio to another.

|

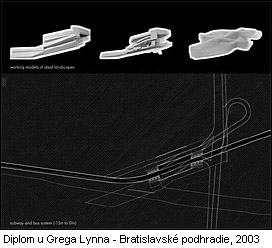

At that time, I was already trying to somehow encode the space so that it could be manipulated. Conceptually, I had three ideal developments for that area, recorded compatibly so that their forms could be mixed: spatial - shops and offices, planar - a park, and linear - transport. The result was an optimum among ideal states that met various criteria in one object of quite complex geometry. However, there was no computer script for that, but manually animated spatial keyframes.

You had the opportunity to compare the pedagogical approach of Greg Lynn and later also his teacher Peter Eisenman at Princeton. What is the difference in their methodology?

I went directly to Greg for my diploma, so I didn't go through his entire program. I was significantly dependent on my methodology. However, right at the beginning, we were mapping and modeling a potato, which included designing the necessary instruments. From that, we all quickly gained the fundamentals on which he built - complex geometry of surfaces and critical use of technologies. With Peter Eisenman, neither geometry nor technologies played such a significant role; there was a great emphasis on documenting the entire process and project step by step, although recently those steps were supposed to leave confusing traces. It was important to push those procedures further based on selected theoretical texts.

|

Europe has the advantage of having many centers; in America, most of the action takes place on the coasts. So even in Central Europe, there is also Berlin, but there are also quite a few smaller cities that are small and fierce. But I have never fully lived in Vienna except for one year. At that time, the dual city of Vienna-Bratislava was a reality for me: in the evening I was in Bratislava and in the morning in Vienna. And I could envision that for the future as well. Vienna is well-connected to various currents, and Bratislava is bold and does not have a tradition. You can reach either city in about an hour. Maybe it's a bit like Amsterdam and Rotterdam. I felt that Vienna was excited (in certain circles) that it was no longer confined. Once it was one of the clear European cultural centers, but then, with the Iron Curtain, the exchange with the East declined, and a certain diversity was lost. When I studied there, I felt that a lot of potential energy would come from reconnecting, from Vienna moving from a border zone to the center, similar to Bratislava. The larger and better-connected a city is with its surroundings, the more specialized and diverse it can be. Vienna has a great interest in culture, and its support is strong, especially from the government – unlike the very substantial private support in New York. However, it has two million inhabitants, while New York has eight.

Isn't Vienna a bit conservative?

It depends on what you compare it to. Maybe in comparison to London, but certainly not compared to Slovakia or the American periphery. It may focus on "higher" culture and perhaps lacks a trash culture in places. In Austria, they also have their political vision of what culture they want to present – why was the Guggenheim ultimately not built there but in Bilbao? I think the more open Vienna becomes with the arrival of new people and neighbors, the rougher and more aggressive new Viennese offices will also become.

|

Certainly, NYC is my favorite city! It is hard to leave. It was easier then because I didn't have any money. Now there are other reasons... It is also a very European city – in culture and density, a kind of interface with America. You can read the possibilities of its inhabitants from every city. And for me in New York, even back then the most evident thing was the image of personal freedom, but also a certain consideration and optimism.

After graduating from Angewandte, you spent a "preparatory" year in Bratislava. You started as a doctoral student at VŠVU, and then you won a Fulbright. What about our education system?

In my opinion, VŠVU has a future. Imro Vaško does a good job leading the department, trying to introduce some working models from Western universities. The most important of these is the critical evaluation of work, and I am struck by the difference in the level of discussion between our schools and the West. This stems significantly from the curtailment of free discussion in the past and the lack of exchange of opinions, especially in the humanities. Recently, VŠVU has succeeded in inviting interesting foreign guests to lectures and commissions during project presentations. I believe that only by comparing ourselves with the world can we identify which of our ideas are truly innovative, and such searches need to be supported more strongly. It is not only that original research is generally insufficiently supported here, but the proportion of research outside science and technology is not valued.

Do you plan to teach again in the future?

I think it’s unavoidable. Because innovative practice requires research. But research cannot all be done just in the office, as there isn't enough time to establish a theoretical basis when following commonly accepted terms. That’s what the university is for, although in our case this aspect is missing alongside student preparation. In science, there are sometimes places for pure research, but in architecture, it intertwines with teaching. And so, I will start looking for something.

|

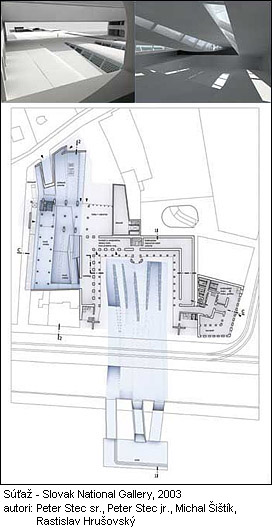

Competitions can present a specific opinion about the city; we wanted to try some new ideas. It was important to find out how we can organize ourselves, but for success, especially further in Europe, it is necessary to build a strong background. It seems that, alongside contacts in Bratislava, further development and exchange of ideas will require a connection with another city. And regarding my experiences with how competitions are organized in Slovakia, I hope that the ambition of awarded solutions gradually increases and that some competitions will also be interesting for good foreign studios, like now with the competition for the National Library in Prague. There, the issuer was interested in an original project and ensured broad participation and a good jury. I am convinced that interest in thoughtful, bold buildings as a counterbalance to projects aimed at short-term profit will continue to grow. It is a pity for formal competitions that do not take advantage of the opportunity to attract and select unusual ideas.

Was the construction boom a shock to you when you returned to Bratislava after two years?

I only saw some buildings. However, I haven't managed to check out much yet. For example, the tower right next to the pylon of the SNP Bridge probably didn't have to be there; the contrast of the bridge with the park should be preserved. But otherwise, I have nothing against skyscrapers; it would just be necessary to create more zones for them because you cannot expect that the location and height of each of them will be determined. However, I believe that Bratislava is deeply underpricing itself by selling huge chunks of the city to large investors, even though those lands could be divided among multiple people who could creatively develop those lands and achieve diversity. The central master plan usually has a rather sparse density of ideas, even if implemented well. In successful current districts worldwide, as well as in medieval cities, you can observe ruptures between varying interests and logics that, ultimately, enrich the district by supporting more complex connections. I enjoy seeing Bratislava develop, even though it might be appropriate to import another two million people to increase its significance. Alternatively, it could connect with Vienna.

You chose another school, Princeton in the USA. It is a private school; how did you manage that?

Princeton prides itself on accepting and supporting those who would otherwise not have the funds for study. I received a Fulbright scholarship for my stay and research in America, but the university also covered part of it. Since I already had a professional diploma in architecture, I completed my postgraduate work in just a year and a half. With an American BA, a master's program takes two to three years.

The school’s budget is over a billion dollars annually. Is it well-equipped with services?

Yes, Princeton takes great care of its students' satisfaction. Libraries are open until midnight, and the school is open 24 hours. We architects had a fully equipped workshop, complete with a 3D mill, laser cutters, printers, and more. There are gyms with pools, courts, and lively social events that the school strongly supports. But the most impressive thing is the level of the professors and their teaching.

Did you often go to NY?

Yes, the distance is like that between Bratislava and Vienna. But when it comes to happenings in NY, there's no time for that when school gets tough, and it usually gets tough for about two-thirds of the semester. However, whenever I found a free weekend, I went.

|

I had two studios there: Eisenman’s and Jesse Reiser. In the third, I was practically working on my thesis, where I prepared the topic myself, but I had a reviewer - Guy Nordenson, who is a structural engineer, thus providing me with another perspective. Peter Eisenman was among the invited critics at the final defense. Since he liked my work, parts of which I developed in his studio, he offered me the opportunity to continue collaborating with him, this time directly in his office.

How does Eisenman’s obsession with the diagram manifest in practice?

In Eisenman’s critical project, the process is layered and from which the diagram arises. Of course, that diagram is cleaned for a long time to derive the rest of the building from it. But I don’t think that process is too strictly defined. What I like about it is that he spends time on it, as if he shifted the complexity of layering reality into the complexity of creating the project. In Eisenman’s work, history and memory are also significant components of this layering. Palladio and modernists like Le Corbusier continually emerge in his work. From what he taught at Princeton, we gained an overview of the canonical buildings of the 20th century. He engages with Renaissance architecture at Yale. Being critical with him also means that he tries to capture some formal principle from history and then vary it. In my understanding, this might also lead towards a kind of record where a code could be found. We will see where this goes from here.

Doesn't this American obsession with history stem from a lack of historical layers that are a given in Europe?

I've heard similar opinions from my American colleagues. However, the obsession with new theories of architecture, as they corresponded to the times, was once even stronger in Europe. The obsession with history and new theories was usually brought to America either by Americans who worked or studied in Europe, or European emigrants during World War II and after, until they drew the focus of the discussion to American universities and institutions like the New York Institute of Urban Studies. Conversely, sometimes in Europe, tradition, along with often underperforming universities, causes stagnation in the historical and theoretical understanding of architecture.

Let’s return to Karl Chu; since when have computational systems fascinated you?

When I started studying in Vienna, I didn't know anything about him; I just spotted his seminar bulletin and immediately engaged with it. I was interested in the abstraction and the possibilities of computational systems in the emergence of form and architecture. However, even though I still try to formalize certain procedures that refer to themselves within a closed system, it is, in a certain contradiction, to the complexity that stems from the endless inputs of reality. For instance, the bending of a beam could influence its shape, which would be thicker in the middle if it’s freely supported. That could be considered some kind of diagram of gravitational forces. But let's say Mies Van der Rohe consciously abstracted it, and he designed it flat, for instance, for Crown Hall. So while I think it will be impossible to avoid creating computational systems, another question is to what extent they should evaluate complex inputs from reality, and what the ratio of their internal relationships referring to themselves is – one of the meanings of abstraction.

|

I find it fascinating to create some abstract sequence of steps, and you can then just select from the results, allowing for a distance that enables you to obtain more unpredictability. Of course, in reality, it functions in such a way that the selection is quite rough, and you continually return to the beginning to "reshake" it again. It's quite difficult to start it in such a way that in the end it becomes a building.

Don't you think that if someone believes in such an approach, it doesn't matter whether it is applied in architecture or, say, in sculpture?

I believe a similar approach can be found in other areas when they work with some form. Eisenman is particularly proud of how he did good form by destabilizing and smudging it, providing an opportunity for flights into arbitrary results. The results can also be formally indescribable if you go through datascapes like MVRDV or if you take abstract steps like Eisenman, which have nothing to do with functional use. There lies a fine line between randomness and order, with which various levels of randomness seem to imitate each other. Similarly, in Koolhaas's La Villette, through layering multiple grids, in the final result, you don’t even know what you have. It consists of strips of various functions, horizontal skyscrapers. Through that, you also have, for example, a grid of hot dog stands. A certain area, across it a certain grid that has a certain rhythm, a grid of sandpits, and so on. When you layer those grids multiple times, the final result is indefinable. That is Eisenman's interest. Either you create multiple systems that you layer over each other, or you create some rules through which you act on the form, but the result in both cases can no longer be traced back. In the station that Peter is now designing for Pompeii, he extracts and layers various grids from the city – a Roman city versus a Greek city. As this occurs only on the surface of a certain fragment, traces gradually disappear. In contrast to his recent book "Tracing Eisenman," which tries to track his architecture, he now aims to leave enigmatic traces. He himself cited Michael Haneke's film "Code Unknown" as an example, where inscrutable traces are shown in a different way hinting at some logic that seems decipherable, but ultimately is not.

|

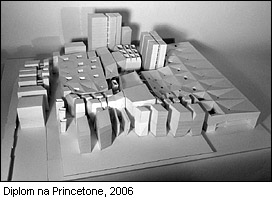

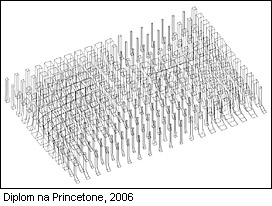

One of the precedents for me was his memorial in Berlin, but it is true that the exhibition at MAKi further pushes the grid of the memorial into a position where individual elements already contain an internal space. However, I also reached the topic of articulating spaces with inserted elements through the analysis of hypostyle spaces. Through examples of such spaces - column halls of antiquity - I developed the possibility of partial division of space, different from the hard boundary of walls.

The theme of blurring boundaries?

Yes, I tried to look at the Greek tradition of column architecture, which Wittkower positions against Roman wall architecture. By passing through rows of columns, the quality of space changes gradually, whereas passing through a wall changes it immediately. Of course, there are also more contemporary precedents - Toyo Ito in Sendai has columns that connect into super-columns with internal spaces. Agadir by OMA is articulated through various scales of columns, from thick hollow columns in certain points, through rows of supporting columns to planes of thin hanging columns that serve as a veil, similar to a forest. Corbusier's La Tourette gradually alters the density of the load-bearing structure between floors to relate to the concept of lightening the monastery downwards.

And other themes?

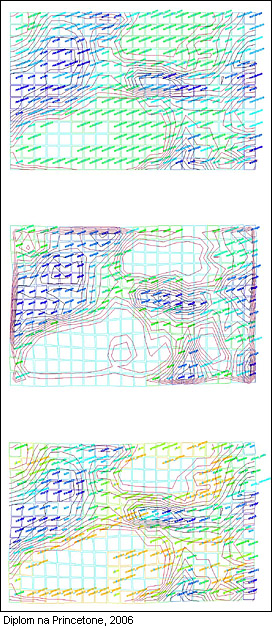

One was creating an "engine." This is a program that commonly processes inputs, for instance, in games. An "engine" can be sold and used for a completely different game with a new environment and characters. So in my project, I wanted to predefine some links and an abstract idea that could then be automatically applied to various places and different functional uses instead of being entirely custom-made. This definition is enabled by a new form of coded notation. The more precise it is, the more complex results can be achieved by changing variables such as the location or use of the project. Another theme was working with expanding and contracting the basic grid. Its spans were altered using an algorithm so that they created various zones from high tubes and dense intimate spaces to open public halls and areas. One of the consequences of this geometry was the negation of the building as an object and the fragmentation into interconnected elements.

How did the floor plan emerge in your work, the initial layout of functions from administration to exhibition spaces?

The surroundings played a certain role as one type of input; large continuous spaces to the north actually expand the existing exhibition hall, while to the south the project smoothly transitions into incoherent industrial development. The program was another variable, expressed as a percentage share of the hotel, parking, shops, exhibition halls, and so on. These shares were interconnected with their ideal spaces expressed as spans, heights, and other criteria of basic elements and blended in such a way as to be in some kind of continuous cloud of smoothly variable densities.

Something like self-organizing maps?

The basis was a simpler automaton similar to those from Wolfram's "A New Kind of Science," and it was less optimized. There could be multiple disjoint areas of the same quality. Additionally, the organization of the cloud of densities was just one part of the whole engine, influenced by various types of inputs. Otherwise, it should all be exhibited this year in Bratislava.

|

Alongside the previously mentioned leaving of undecipherable traces, Peter was also interested in questions of centrifugal and centripetal movement: while in Modernism, the composition of movement was centrifugal, where the density increased towards the periphery of the plan, he was interested in "vortex," an oppositely oriented, centripetal composition. Additionally, he was interested in developing the possibilities of fragments as a whole. These two topics were related to some aspects of my work from Princeton that interested him. The first project I worked on with him, a school and museum of fashion in Milan, uses this centripetal kind of movement, reflecting in the densification of columns and wrinkling of the envelope. A competition in Kazakhstan, led by my colleague, explored the possibilities of multiple buildings as one group. There were two designers working there, each responsible for some of the projects. Designs are often presented to Peter by the entire team, first as diagrams, then in models, but a considerable emphasis is placed at the end on drawings and presentations. He can precisely determine the direction of the design or reveal a problem, for instance, in the logic of the plan.

|

Every month or two, I moved until I found a long-term sublet worth it. But that was the best concept to get to know different neighborhoods, from Harlem to Brooklyn or Jersey City, up to my last stop near the Natural History Museum on Eighty Street. Something is happening every day in Manhattan, but it was best to have guests at home because they discovered everything, and I only had to join in.

You just recently returned; you are on your way to Prague. What are your plans?

I brought back many books, so I would like to go through as much of that as possible now. A good school provides a good overview, but the details need to be filled in, so I want to unpack a few opinions. Alongside that, I want to gain further practice and develop new ideas in the evenings. At Eisenman’s, we worked on conceptual designs, but they were mainly realized by local architects; now, I would like to gain some experience in that area as well. Peter is also interested in where it will be; in this, he can help "his team" quite a bit; he is very nice about it. It seems now that I will exist for a bit between Basel, Prague, and Bratislava.

What about your "martial art" in Slovakia?

If there is a direct commission, I will be happy. I will go to parties and find out who is interested in what... But in reality, it means competing again, hopefully now internationally.

As a cosmopolitan person, where do you see your future work?

I still think about where I should be. Place is very important, but even more is when and how to unpack there. However, I can imagine pendulating later between New York or London and Central Europe, just as I was used to traveling between Vienna and Bratislava before. I’m interested in a multilayered identity. I currently feel like a New Yorker and at the same time a European, which intertwines with ties to Bratislava but also to the Mediterranean.

Thank you for the interview.

Thank you as well.

|

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

1 comment

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

komentar ..od misa

miso -dubajec

31.03.07 09:03

show all comments