At the end of last year, a new theater stage was opened in Brno. Behind the design and realization of the theater on Orlí, or what you want to call it, the Music and Dramatic Laboratory of JAMU, are architects Milan Rak, Alena Režná, and Pavel Rada. It is interesting that the design of this theater emerged from an architectural competition. And it was precisely about how long the journey was from winning among almost fifty proposals to the final realization that we talked with Milan Rak. At the end of last year, a new theater stage was opened in Brno. Behind the design and realization of the theater on Orlí, or what you want to call it, the Music and Dramatic Laboratory of JAMU, are architects Milan Rak, Alena Režná, and Pavel Rada. It is interesting that the design of this theater emerged from an architectural competition. And it was precisely about how long the journey was from winning among almost fifty proposals to the final realization that we talked with Milan Rak.The proposals of ARCHTEAM were recently present in several domestic competitions, often among the awarded and recognized works. The ambition to win a significant public contract in the competition seemingly balances with a completely different type of contracts, through which ARCHTEAM has also entered wider awareness – designs of affordable type houses that far exceed the domestic catalog average. And although Milan Rak, with his thoughtful and simple designs, cannot compete in the number of realizations with the flood of the most despicable and still the most popular "smurf" houses, he evidently does not suffer from a lack of work even in today's times. Even so, just to be sure, at the end of the interview, he gets up from the glass table and, so that luck does not abandon him, goes to knock on the wooden bookshelf...

I come from Hronov. At the end of high school, everyone thought that I would study medicine, but I wanted to do something creative instead. I wanted to create something with my hands. I chose Brno because it seemed friendlier to me compared to Prague. I attended open house days in both Brno and Prague, and the school in Prague felt impersonal. Conversely, in Brno I saw old, bearded men smoking on the landings and thought to myself, this is the right school! Just before the end of your studies, the revolution caught you. How did you experience that period? That time seemed amazing to me, even though at the time one did not know how long it would last. I was in the last year, which was leading at the school for the revolution. Moreover, in Brno, architecture together with the Faculty of Philosophy was the most active in the revolution. Today I think it got out of control in some ways. I don’t call it a revolution, but a student movement that was misused for a political coup. I precisely remember the student demands of that time, which, however, do not demand what is here today... How and when did ARCHTEAM arise? We founded the studio with my wife right after school when we moved to Náchod. However, we didn't start by sitting at home. We immediately rented a large office in the square and gathered quite a few people; there were eight or ten of us then. Gradually, we started to find work. The euphoria after the revolution contributed to the fact that in the beginning we did things that often did not lead to realization. Many people had intentions back then that they did not follow through. Theater on OrlíRecently, the Music-Drama Laboratory of JAMU was completed in Brno, or better said, the Theater on Orlí. You won this project based on a successful architectural competition. How do you remember this competition?

The competition took place in 2003, and the designs were submitted before Christmas, of which there were ultimately 49. The results were announced in early 2004. We were thrilled with the win. It was the first competition we won.

What was the process between winning the competition and subsequent realization? The process was mainly long. JAMU was satisfied with the proposal and explicitly wanted to proceed with it. And they had a grant, so it was clear that there were no obstacles to realization. But a series of administrative steps followed. At that time, there was a different law on public contracts, so we had to tender the project again. But everything turned out well. The project started in 2005 and continued until 2009 with three breaks. For example, there was a year’s pause when they needed to make some adjustments to the grant, and there was a lack of governance at the ministry. Outside of these pauses, however, the design work always went quickly; we had a stipulated time for it in the contract in the order of months. The realization was ultimately also tendered twice due to some appeals, which caused additional delays. Construction did not start until mid-2010. Just as the project was complicated, the realization ended up being difficult as well.

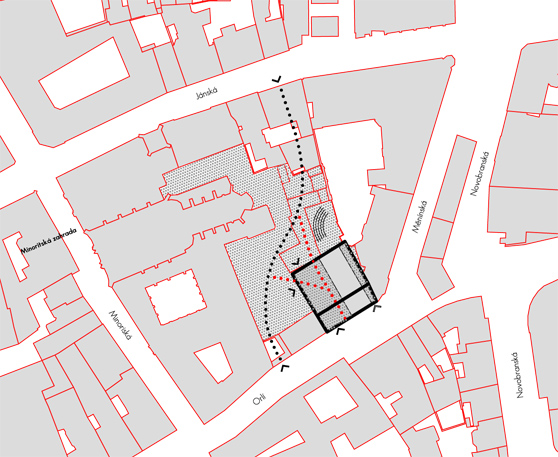

We considered that it was important that it was simple and rationally arranged to fit everything in there, and we tried to manage that from the beginning. After all, the design in the competition was simple and clean, and it looked as it was ultimately realized, except for the façades, which developed in some way. In competitions, we always want to have buildings sufficiently resolved, so we know that they can be pushed through in case of realization. Even so, the project and realization gave us a lot of work. We struggled, for example, with restrictions imposed by the specific site. The plot measuring approximately twenty by twenty meters had to be used to the maximum both in terms of footprint and height; there were certain limitations. To accommodate everything that was requested by JAMU, we had to go to the limits everywhere; there was no room for undercuts where various installation systems could be hidden. At the same time, we always tried to solve everything simply. The rationality of the solution had to be from the concept to the last wire – and there are dozens of kilometers of those wires there. The construction was limited by historic basements due to the demanding static and foundation requirements. Besides me and Alena Režná, the author of the Theater on Orlí is Pavel Rada, with whom we used to work together in the studio on Černopolní street. However, during the work on the project, we moved with ARCHTEAM to new spaces at Svobody Square. Our new studio turned out to be very practical because the theater construction was literally around the corner, allowing us to be there every day, sometimes even several times a day, and towards the end practically all the time. When it finished before last Christmas, we properly sighed in relief. It simply required an incredible amount of energy and time, fights, negotiations, and dealing to have it built like this and to keep the essential things – and everything was essential! But it seems to me that it has turned out quite well. Although some things are still being fine-tuned, we mostly go there with tours now. And we are satisfied with it! I was very interested in how a part of the ground floor was left as part of the public space. How did the idea of opening the ground floor to the street come about? And what is your vision for its use? We had a similar solution in the competition like no one else. The plot is part of the largest courtyard in the center. The authors of several other designs proposed the largest mass directly in the courtyard, while we wanted to leave it open and only built on the street part of the land. The regulation plan for the city heritage reserve included a planned passage through the Minoritská Garden, between Orlí and Jánská streets. The Minoritská Garden is supposed to become a publicly accessible green space. However, the passage was planned a little differently; we suggested it more simply and directly so that it would not be such a burden for the Minorites. The passage through the entire courtyard has not yet been realized. It is a matter of agreement between multiple entities. JAMU is inclined to it. The people at the Minorites change; they were favorable to it at that time, then not, and now it has improved again. But mainly, the city would have to show some effort and interest. Access to just the garden is also possible without continuing the passage to Jánská street, but even so, as it is now, it might take many years. After all, the passage was not the only motivation for this solution. Mainly, we designed it as an outdoor vestibule. The lower part of Orlí street is quite narrow; cars park in it, and there is no possible dispersal area. It serves as an entrance hall so that people do not have to stand on the street among the cars when going to or leaving the theater. All three entrances were made from that covered area – therefore not directly from the street. However, the vestibule is not yet fully furnished; JAMU plans its equipment for this year. There should be some seating that will function as a summer garden for a pub, allowing students to discuss life, art, and smoke. It will be overgrown with greenery, which should then grow on the façades. The space also functions as an outdoor stage; there are necessary electrical connections and low-voltage systems for the outdoor stage. When Kometa plays the finals or playoffs again, it can be watched there.

Does this theater have any specific operations compared to other stages? From a typological perspective, it is a combination of cultural and educational buildings along with a pub. It was necessary to consider that guest performers may come, providing them with dressing rooms and the necessary facilities, but also the students who are there every day and have their daily rooms, classrooms, and rehearsal rooms. What is the status of the planned green façade? Why did you even propose it? The concept of the design consists of dividing the cube into a front lower and a rear higher mass. We then tried to dematerialize that rear one; we wanted to make it a natural block overgrown with greenery. Once there is the accessible garden, that will be the façade facing into it. As the project developed, the façades changed, so now the mass distinction is already sufficiently emphasized by the material. The front part is white, more pronounced, and the back is black, subdued, blending into the view. So we no longer perceive the greenery as an absolute priority, and it could just as well remain as it is. However, everything is prepared for it to eventually grow there. What will be visible from the street will grow quickly; it will take longer in the vestibule. The specific greenery was designed by Zdeněk Sendler, and he is a guarantee that it will eventually grow. Twenty to Ten to One

Even in the 1990s, we participated in some invited but chamber-sanctioned competitions in our region. I wasn't very enthusiastic about that back then because it seemed to me that it was always decided in advance. The first more important competition we participated in was in 2000. In 2010, I prepared a lecture regarding ten years of our competition participation. So I calculated that we have done twenty competitions, received five awards and five prizes, meaning we were successful in half of the competitions. However, only two projects emerged from that, and ultimately only one realization – which is exactly JAMU. And that is quite pathetic... Does competing have any sense then? What is your main motivation for participating in competitions? Often it is about the desire to solve a problem and then show that solution. So it is not just about getting a contract; it has to be an interesting assignment, with a good jury, and it must seem that it makes some sense. And I think that in recent years, this has been disappearing from competitions...

In Hradec Králové, originally Gočár designed two offices, the district office and the financial office, which were not connected; there was only a passage between them. Therefore, the entrance hall, which this competition was supposed to address, was missing. Officials were supposed to walk into this entrance hall and serve the public. This idea came from the original secretary, who was in the Netherlands on an internship and saw an office open to people there. We submitted two designs; one received an award, and the other won. Subsequently, we made a project for a building permit. But then the leadership changed there, and there was already no interest in it. Unfortunately, it doesn't look like anything now. They quietly buried it. Another success of yours was the first places in competitions for the office in Prague – Dolní Měcholupy or for the community and cultural center in Kuřim. Did any realizations come out of those either? We won Dolní Měcholupy shortly after Hradec Králové, also in 2005. It was about the reconstruction of an existing building and its extension. We received the first prize, but they then commissioned a real estate agency for the solution of that project. Conversely, interest in Kuřim persists. We are slowly collaborating there. Model HouseARCHTEAM, like one of the few Czech studios, has a number of catalog family houses in its portfolio. How did you come to the decision to also design this category of houses? We reached this after about fifteen years of development. We were inspired by what people need, what kind of houses they want, and also what houses are permissible to build. The majority of our buildings are family houses and are mainly concentrated around Prague. There are villages nearby which all have regulations for gable roofs and similar styles. At the same time, it essentially pained us for those people, who often fear to approach an architect because they feel they cannot communicate with them. They often fear that an architect will create a monument to their image, and that they will be proposed an expensive house. Therefore, they often prefer the route – and have no other option – of buying a catalog at a gas station or drawing it themselves at home and then giving it to some company to slap together. We wanted to make it easier for them somehow. So they could have quality modern buildings – in terms of architecture, operation, or utility value – and so they could see what those houses look like, how they work, and how much they cost. The plots and the clients' ideas are often the same, typological, so we can often respond to them in several typical variants. Therefore, we created our catalog around 2005. So do you design houses directly for the catalog, or do you modify originally individual projects? Some houses are designed purely for the catalog, while others were created by modifying an existing project. We prefer to call the catalog houses "model houses." I want to slightly differentiate this from typological houses because it has been somewhat unjustly discredited since the era of typological construction in socialism.

What is the reason that other architects tend to avoid proposing typological houses? Perhaps they think it is beneath their level. However, I believe it is quite the opposite. After all, an architect creates the living environment in its entire spectrum, and satisfying housing is the primary need of people. So why make architecture only as an exceptional thing for a few people? Why can’t it be widespread? And what is the way to do it? We found our own path.

Clients either order a house from our catalog or they want an individual house. In individual projects, we do not show them the final result in advance, but we indicate how we do individual houses in our gallery of realized houses, so they have some idea. When we arrange a meeting with a potential client for a model house, the client often already knows what they want, has some idea, and has studied what we offer. They show us the plot, and we help them with selection from the catalog. Or we say that it is such an exceptional plot that we cannot select a house for it and recommend that they order an individual project, which we will then create for them. However, we do not make the catalog houses as if someone buys a catalog from a gas station and then orders a package for fifteen thousand, in which they have everything from execution to electricity. They will still throw it away because they find out that they don’t have usable foundations, that it doesn’t turn where they need it, that they need windows elsewhere... We offer the project with placement on a specific plot and other adjustments. No house of ours is the same. They always differ in some way because each place is a little different. So what do you think is essential in architecture? What do you rely on the most when designing? On the place, on urbanism. Today, this is not much addressed; practically, it is not taught even in schools, where students focus on some exhibition instead of solving the place correctly. This is what is essential. The greatest damages can occur there, or it can be resolved best. Then, operation is important for the building to function. It is not important for the house to be skewed because of its architectural impact – be it from an urbanistic or operational perspective. The architecture we create could probably be classified under minimalism. We ourselves call it "artistic minimalism" because there are certain artistic elements in it. It probably doesn’t all go together completely, but our houses are simple, clean, yet have some artistic element or impact. How are you doing now, when there is still talk of a crisis in construction? We do not feel the crisis much. We have never done many houses for developers. Other colleagues were dependent on that, and often they have either thinned down or even dissolved their studios. This hasn't affected us at all because we did not have such contracts. I always thought it was a pity, but now it has turned in our favor. I do feel a gradual decline in family houses, but not from day to day. It’s not so much due to banks and mortgages – which are favorable today – but due to the general mood of people, whom media scare with what is happening now – they see executions and unemployment everywhere. Thus, one is not rushing into building a family house as before. But on the other hand, there is a lot of work in spatial planning right now. We have been doing spatial plans since the 1990s, and even today, few people combine spatial planning and architecture. Although, today many are trying to make spatial plans, and it is evident. We are currently working on an interesting new building, an entrance building to the Stiassni Villa complex for the National Heritage Institute. It will be located on the upper edge of the slope above the villa on Preslova street. A bistro and reception are planned there, and a lecture hall will be below. The villa itself is an exhibition, while this will primarily serve as a background for events, conferences, training, etc. And just as JAMU was extremely demanding, this project, on the other hand, is quite pleasant, and the realization is going smoothly. We hope it will be finished by the end of this year.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles |