Otakar Novotný: Architectural Impressionism

Source

Časopis Styl, roč. IV (1911), str. 105-107, 123, 126-129.

Časopis Styl, roč. IV (1911), str. 105-107, 123, 126-129.

Publisher

Petr Šmídek

16.06.2013 20:15

Petr Šmídek

16.06.2013 20:15

Otakar Novotný

The Czech countryside until recently did not lack the organic unity of a person with their dwelling, that is, the harmony of needs and life customs with living form. Only in rural buildings could one still trace the principle that the way of life conditions the architectural form of its surroundings. In close relation to both factors, it is also fitting to seek "the sacredness and charm of the family hearth," which is certainly not possible in the absence of a stable and firm home. The difference between the nomadic system of urban housing and the settled life of the peasant population is striking and results in different life formations and a different character of dwellings. Differences were certainly easier to observe in earlier times than now, when the gravity of the countryside towards cities releases love for nature and land, even disrupting nationalism. For the more refined urban life, more intense and nervous, requires heightened mental energy, in many senses uplifting culture and balancing its deficiencies with cosmopolitan views. A strong race, however, does not drown but is leveled and polished. A strange brake here is precisely the instability of the dwelling, which does not allow for the development of all human capabilities that could culturally be the seeds of a new merging of ways of life with its external form. Thus, the mode of an unstable dwelling is an obstacle to a clear expression of life outward. — It seems that the remedy begins with the effort for one's own house; the reasons for such tendencies are certainly not solely ethical; they are primarily of economic origin, but in that case, they also signify a rebirth. We may again reach solid settlements, not under former patriarchal conditions, but simply because the ease of overcoming distances in communication will not hinder the expansiveness of inhabitable territory.

Then the dwellings will again breathe the charm of their immediate connection with the lives of the inhabitants, but the connections will be achieved on a very broad cultural foundation, which will vastly exceed today’s small scale.

The countryside is still almost exclusively the domain of old settlers, traceable far into the past. From here one can understand the traditional appearance of rural buildings, both residential and agricultural, to which wealth brings external adaptations and renovations, while poverty leads to neglect, which, however, the ongoing industrialization and urban pseudoculture could not have harmed so much that there is something here to be changed about the accomplished type; today’s way of life does not yet have the strength to violently change and overturn principles, but it does have a very questionable influence on the logical formation of exteriors. The fact is not new; in all eras, advanced urban culture acted in a certain sense destructively on the naïve soul of the villager and architecturally led to primitive replicas of urban buildings. Although architecturally correct embryos were present here, despite the fact that the building as a whole can be regarded as a correct synthesis of all components defined by the program and circumstances appropriate to the countryside, it is still used for decorative embellishment, unnecessary, joyful, and lush, by imitating urban forms, used with charming naivete and considerable carelessness. Strictly critically speaking: in the works of the folk there is always a lot of amateurism, and so the rural builder reaches an impressionistic expression of their architectures, this easy starting point between effort and ability, between lay enthusiasm and cultivated discipline, between art and science. This can explain the reminiscences of urban buildings, with decor unconsciously and illogically conceived, with little pillars that rest on nothing and bear nothing, with archivolts without bases, with oddly notched and curved gables, and so forth; everything is accompanied by glaring coloring, barbaric to those who have not recognized the merging of dramatic colors with sunlight. However, naïve replicas such as those that have still been erected cannot be expected anymore, because the expansion of industry and the convenient connection between the city and the village will not only equalize social differences but also intellectual ones of the inhabitants. The countryside already does not maintain the former approximately thirty-year difference that used to separate it from the more advanced city; in the future, the temporal difference will be reduced to a minimum and will disappear.

That strange impressionism is very old and still lives on; even now, buildings derived from urban modernism are emerging in the countryside, which, lacking all whimsicality and replacing it with primitivism and simplicity, will still have a right to evaluation, provided they at least maintain the necessary tectonic principles in their basic dispositions.

Also locally: As the settlement moves away from the center, its imitative capabilities decrease. Nevertheless, there can be found in the Czech countryside remote municipalities and regions where folk architectural "art" nearly reaches a certain classicism; however, such manifestations are exceptions and can be explained either by the extraordinary wealth of the region or cultural maturity (mainly conditioned by religious confession in previous centuries), or finally by the commendable influence of an individual, the owner of the estate or court. A separate chapter consists of peasant and noble estates in the immediate vicinity of the city, indecisive in their character as either urban or rural, but entirely decisive in expressing their conditions and purposes.

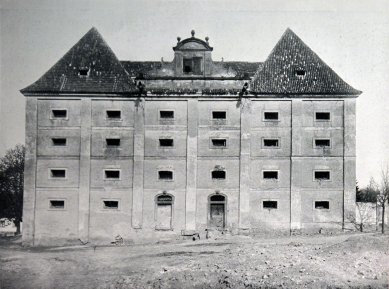

Spatial and temporal distance complicate with peculiar local conditions, so that only by overcoming many difficulties of historical inquiries can the final formal results of folk buildings be explained and analyzed. The intensity of the capital allows well-observed style forms of Baroque, Empire, and pre-March styles to occur in the vicinity, which are coarse and vague, often used violently and inappropriately; the further the municipalities are from the center, the more helplessness increases; isolated cases of certain perfection must be attributed to random work by an urban builder; finally, if reminiscences are insufficient, one has only to borrow motifs from elsewhere.

If there are different conditions for building a relatively rich dwelling, ornamental motifs are added to the simplest tectonic form, which, according to common perception, are called folk and are actually analogous in provenance to historically architectural forms elsewhere in the countryside; however, they are temporally more distant from their origin, making it generally difficult to trace the actual source.

The stagnation set in urban construction in the early nineteenth century occurs in the countryside, near Prague, until the thirties, in more distant municipalities even later; from the sixties, we indeed have surprising products from Czech South, Wooden buildings, of course, deviate from similar considerations, since the countryside, being self-reliant, was forced to create from scratch; however, the easier processability of the material was a significant relief in finding a few basic shapes.

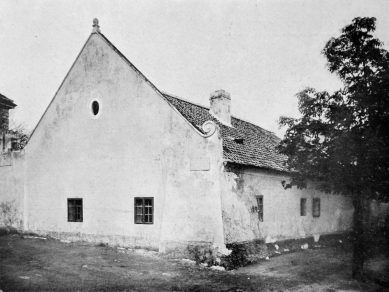

Agricultural buildings retain a utilitarian character until recent years; with lapidary clarity, they develop their interiors outward, generally providing no more than absolutely necessary; the occasionally appearing non-essential decor can only be explained by prosperity and the resulting exuberance of life.

The joyful and surprising outward acclimatization of rural buildings to their surroundings is certainly not the result of any special architectural talent of the author, whose certain impotence has been proved here. It is not a complete harmony with his creative ability; it is, however, a temporal reconciliation of nature and human product. The peasant has a certain advantage: the possibility of drawing simplicity and truth from nature; yet he only uses this in disposition and dimensions, in materials and construction, thus in practically building questions. In decorative architecture, he is only a naive weakling, imitating foreign accomplishments; he is merely a lyricist of great intuition but small intelligence.

Czech architecture of rural brick buildings is therefore not an original and will not be. There is no folk art as it is understood today, a manifestation of racial strength, nor will there be, since social conditions prevent the immersion of the people in the beauty of nature and since the beauty of art must embrace the laws of mutual ideal, humane, and social harmony; and these are today so complicated and such a problem that the simple spirit of the villager cannot cope. Today's, or more accurately, almost century-old character of the countryside cannot be preserved even by questionable and violent adherence to traditional forms, as is currently happening in Germany, as has not ceased to happen in France since the Empire, and as has generally been the case in England, nor by technical backwardness and anachronisms (the impregnated thatched roof, the prevention of slate coverings, the effort for a folk style of the countryside), but also not by garden cities, which in fact have a completely different purpose and introduce misunderstanding of rural tendencies. Efforts will already be needed to maintain the overall disposition of village squares; whether cyclical or in the form of a rectangular marketplace, or merely expanded road communication.

The development of architecture, including rural, cannot be restricted by a common standpoint of protecting the homeland. Impressionistic architecture of rustic buildings preceded other arts; at a time when impressionism in painting and sculpture is completed, and in music it is fading, architecture has long since lost its impressionistic character and is forming rationally and scientifically. The creation with evident positive results is, of course, complicated by the rapid development of technology. Europe is becoming Americanized; this means that as a consequence of the current rapid pace of invention, artistic architectural creation, calm and deliberate in its nature, is lagging behind or will work differently tomorrow, on different assumptions than today, that it lacks solid ground and loses interest in rational solutions to ephemeral tasks.

The current speed of life does not allow one to gamble with time and energy; thus, one must work in two ways: either one should endeavor honestly for a quiet, unobtrusive development of modern tendencies, which are already fairly well-known and respected today, by avoiding hasty, violent oddities, or there remains the second option: a careless play with forms, of which we know that they are ephemeral and which beyond the immediate interest of an expert will leave no strong impressions.

Today’s architect has no time to concern himself with the creation of heating elements that are continuously evolving, or the form of lighting elements, of which in the future, due to advancements in lighting, perhaps there will be no need at all, and thus it becomes that contemporary products lack the sap that only tradition supplies, yet at the same time, what we lose in detail we gain a hundredfold in the whole.

Impressionism in architecture is therefore as a separate element not only a relic but also a very harmful element for the proper progress of modern architecture. In the Czech countryside, however, it closely relates to rational architecture, self-serving, purposeful, and constructive, and sometimes merges into a single mental product, powerful and invaluable, based on correct tectonic traditions and the contemporary lyrical expression of the creative soul. It is, socially, artistically, and historically, an epoch of healthy racial strength, worthy of methodical and strictly scientific processing.

* The most developed Czech municipalities are mostly inhabited by Protestants.

Then the dwellings will again breathe the charm of their immediate connection with the lives of the inhabitants, but the connections will be achieved on a very broad cultural foundation, which will vastly exceed today’s small scale.

The countryside is still almost exclusively the domain of old settlers, traceable far into the past. From here one can understand the traditional appearance of rural buildings, both residential and agricultural, to which wealth brings external adaptations and renovations, while poverty leads to neglect, which, however, the ongoing industrialization and urban pseudoculture could not have harmed so much that there is something here to be changed about the accomplished type; today’s way of life does not yet have the strength to violently change and overturn principles, but it does have a very questionable influence on the logical formation of exteriors. The fact is not new; in all eras, advanced urban culture acted in a certain sense destructively on the naïve soul of the villager and architecturally led to primitive replicas of urban buildings. Although architecturally correct embryos were present here, despite the fact that the building as a whole can be regarded as a correct synthesis of all components defined by the program and circumstances appropriate to the countryside, it is still used for decorative embellishment, unnecessary, joyful, and lush, by imitating urban forms, used with charming naivete and considerable carelessness. Strictly critically speaking: in the works of the folk there is always a lot of amateurism, and so the rural builder reaches an impressionistic expression of their architectures, this easy starting point between effort and ability, between lay enthusiasm and cultivated discipline, between art and science. This can explain the reminiscences of urban buildings, with decor unconsciously and illogically conceived, with little pillars that rest on nothing and bear nothing, with archivolts without bases, with oddly notched and curved gables, and so forth; everything is accompanied by glaring coloring, barbaric to those who have not recognized the merging of dramatic colors with sunlight. However, naïve replicas such as those that have still been erected cannot be expected anymore, because the expansion of industry and the convenient connection between the city and the village will not only equalize social differences but also intellectual ones of the inhabitants. The countryside already does not maintain the former approximately thirty-year difference that used to separate it from the more advanced city; in the future, the temporal difference will be reduced to a minimum and will disappear.

That strange impressionism is very old and still lives on; even now, buildings derived from urban modernism are emerging in the countryside, which, lacking all whimsicality and replacing it with primitivism and simplicity, will still have a right to evaluation, provided they at least maintain the necessary tectonic principles in their basic dispositions.

Also locally: As the settlement moves away from the center, its imitative capabilities decrease. Nevertheless, there can be found in the Czech countryside remote municipalities and regions where folk architectural "art" nearly reaches a certain classicism; however, such manifestations are exceptions and can be explained either by the extraordinary wealth of the region or cultural maturity (mainly conditioned by religious confession in previous centuries), or finally by the commendable influence of an individual, the owner of the estate or court. A separate chapter consists of peasant and noble estates in the immediate vicinity of the city, indecisive in their character as either urban or rural, but entirely decisive in expressing their conditions and purposes.

Spatial and temporal distance complicate with peculiar local conditions, so that only by overcoming many difficulties of historical inquiries can the final formal results of folk buildings be explained and analyzed. The intensity of the capital allows well-observed style forms of Baroque, Empire, and pre-March styles to occur in the vicinity, which are coarse and vague, often used violently and inappropriately; the further the municipalities are from the center, the more helplessness increases; isolated cases of certain perfection must be attributed to random work by an urban builder; finally, if reminiscences are insufficient, one has only to borrow motifs from elsewhere.

If there are different conditions for building a relatively rich dwelling, ornamental motifs are added to the simplest tectonic form, which, according to common perception, are called folk and are actually analogous in provenance to historically architectural forms elsewhere in the countryside; however, they are temporally more distant from their origin, making it generally difficult to trace the actual source.

The stagnation set in urban construction in the early nineteenth century occurs in the countryside, near Prague, until the thirties, in more distant municipalities even later; from the sixties, we indeed have surprising products from Czech South, Wooden buildings, of course, deviate from similar considerations, since the countryside, being self-reliant, was forced to create from scratch; however, the easier processability of the material was a significant relief in finding a few basic shapes.

Agricultural buildings retain a utilitarian character until recent years; with lapidary clarity, they develop their interiors outward, generally providing no more than absolutely necessary; the occasionally appearing non-essential decor can only be explained by prosperity and the resulting exuberance of life.

The joyful and surprising outward acclimatization of rural buildings to their surroundings is certainly not the result of any special architectural talent of the author, whose certain impotence has been proved here. It is not a complete harmony with his creative ability; it is, however, a temporal reconciliation of nature and human product. The peasant has a certain advantage: the possibility of drawing simplicity and truth from nature; yet he only uses this in disposition and dimensions, in materials and construction, thus in practically building questions. In decorative architecture, he is only a naive weakling, imitating foreign accomplishments; he is merely a lyricist of great intuition but small intelligence.

Czech architecture of rural brick buildings is therefore not an original and will not be. There is no folk art as it is understood today, a manifestation of racial strength, nor will there be, since social conditions prevent the immersion of the people in the beauty of nature and since the beauty of art must embrace the laws of mutual ideal, humane, and social harmony; and these are today so complicated and such a problem that the simple spirit of the villager cannot cope. Today's, or more accurately, almost century-old character of the countryside cannot be preserved even by questionable and violent adherence to traditional forms, as is currently happening in Germany, as has not ceased to happen in France since the Empire, and as has generally been the case in England, nor by technical backwardness and anachronisms (the impregnated thatched roof, the prevention of slate coverings, the effort for a folk style of the countryside), but also not by garden cities, which in fact have a completely different purpose and introduce misunderstanding of rural tendencies. Efforts will already be needed to maintain the overall disposition of village squares; whether cyclical or in the form of a rectangular marketplace, or merely expanded road communication.

The development of architecture, including rural, cannot be restricted by a common standpoint of protecting the homeland. Impressionistic architecture of rustic buildings preceded other arts; at a time when impressionism in painting and sculpture is completed, and in music it is fading, architecture has long since lost its impressionistic character and is forming rationally and scientifically. The creation with evident positive results is, of course, complicated by the rapid development of technology. Europe is becoming Americanized; this means that as a consequence of the current rapid pace of invention, artistic architectural creation, calm and deliberate in its nature, is lagging behind or will work differently tomorrow, on different assumptions than today, that it lacks solid ground and loses interest in rational solutions to ephemeral tasks.

The current speed of life does not allow one to gamble with time and energy; thus, one must work in two ways: either one should endeavor honestly for a quiet, unobtrusive development of modern tendencies, which are already fairly well-known and respected today, by avoiding hasty, violent oddities, or there remains the second option: a careless play with forms, of which we know that they are ephemeral and which beyond the immediate interest of an expert will leave no strong impressions.

Today’s architect has no time to concern himself with the creation of heating elements that are continuously evolving, or the form of lighting elements, of which in the future, due to advancements in lighting, perhaps there will be no need at all, and thus it becomes that contemporary products lack the sap that only tradition supplies, yet at the same time, what we lose in detail we gain a hundredfold in the whole.

Impressionism in architecture is therefore as a separate element not only a relic but also a very harmful element for the proper progress of modern architecture. In the Czech countryside, however, it closely relates to rational architecture, self-serving, purposeful, and constructive, and sometimes merges into a single mental product, powerful and invaluable, based on correct tectonic traditions and the contemporary lyrical expression of the creative soul. It is, socially, artistically, and historically, an epoch of healthy racial strength, worthy of methodical and strictly scientific processing.

* The most developed Czech municipalities are mostly inhabited by Protestants.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles

1

24.04.2014 | Otakar Novotný: Exhibition of the Imperial Royal Academy of Arts

0

06.07.2013 | Otakar Novotný: Agreements and Discrepancies

0

27.06.2013 | Otakar Novotný: Notes on Perfect Compositions

0

27.06.2013 | Otakar Novotný: Architectural Graphics

0

15.06.2013 | Jaromír Pečírka: Otakar Novotný

0

14.06.2013 | Otakar Novotný: The Creation of Form in Architecture