Tadao Ando: Eternity in a Moment

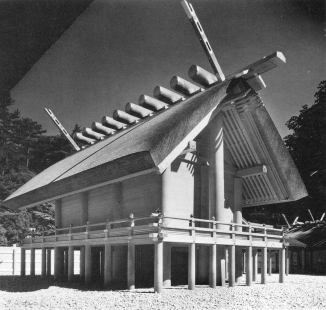

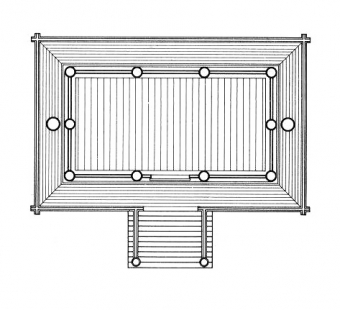

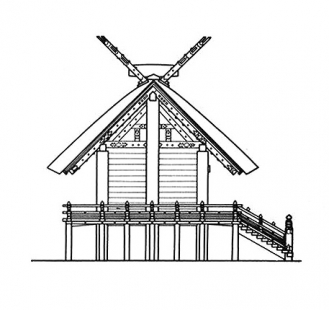

By being born and raised in the historically rich region of Japan, in the Kansai area, I was fortunate to have ample opportunities to explore traditional Japanese architecture in ancient cities - Kyoto, Nara, and Osaka. However, some of the countless and often unnoticed temples and residences I visited had a profound influence on me and left such an impression, such as the temple in Ise. Since ancient times closely connected with the Tenno system, the Japanese form of monarchy, the temple in Ise has become a spiritual cornerstone in the subconscious of the Japanese people. Even today, as the Tenno is still deeply rooted in the psychological framework of every Japanese person, the temple retains deep significance as a residence of traditional Japanese aesthetic consciousness.

As a visitor approaches the temple grounds, they cross the Isuzu River and adopt a solemn and serious mood as they walk along a gravel path through the dark forest to the entrance gate. The temple in Ise, shrouded in silence and exhibiting an impressive beauty of primeval simplicity, seems to be a fitting symbol of the aesthetics and lifestyle of ancient Japanese farmers.

The temple is completely rebuilt every twenty years in accordance with the practice of shikinen-sengu, a custom unlike any other in the world. This involves the regular dismantling of the temple in a settled cycle. This custom, which is believed to have originated during the Nara period (around 750), is still faithfully observed today. On the temple grounds, there are two alternative sites, and while one temple remains untouched, the other, exactly the same, is built beside it. After the sengu ceremony, when the embodiment of the deity is transferred, the old temple is dismantled. Shinto, a religion full of the beauty of ritual, finds its most beautiful expression here. Moreover, there is no surer way to pass down to future generations the method of construction based on ephemeral materials and labor techniques, such as thatched roofs and wooden posts directly set into the ground. Thus, because the temple is reborn every twenty years for over a millennium, the ancient method of architecture has been preserved virtually unchanged.

What is conveyed by the temple in Ise is not the physical substance of the building but the "style" and spiritual tradition itself. In it, we find sensitivity to beauty, simplicity, fresh vitality, and nobility in its most original and untainted expression - which is successfully passed down through generations of Japanese.

While Western thinking relies on individual consciousness, the Japanese traditionally embrace a pantheistic view of nature and leave consciousness to the god that resides in all things. In harmony with this, something spiritual and immaterial is concealed and resides within architectural forms, inherited from bygone times and continuously refined, changing its character. Moreover, since ancient times, the Japanese have tended to discover the eternal in that which withers and dies, feeling that the eternal is intuitively graspable - paradoxically - in that which has only a fleeting existence. The ideal metaphor is a flower, as it withers, losing its petals just when we realize it is at the height of its beauty. Although we might pray for such beauty to remain, nothing in this world is immortal, and ultimately, there is no more fitting symbol of our longing for eternity than that which immediately withers.

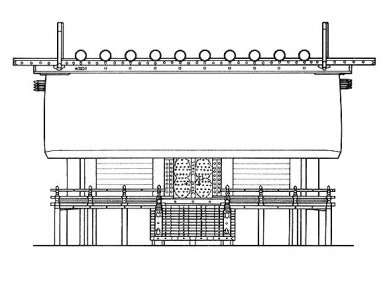

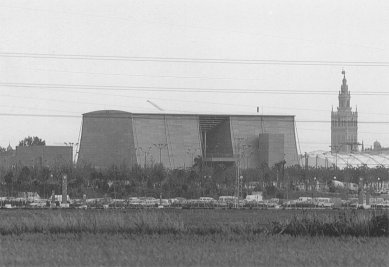

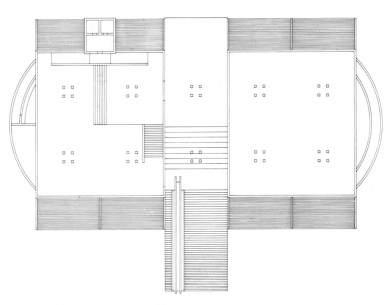

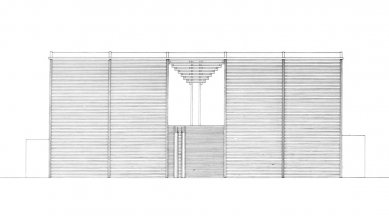

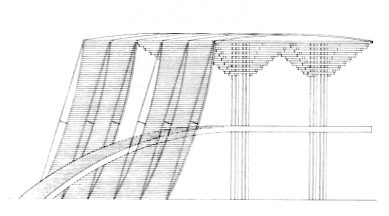

Rather than choosing the heritage of Japanese tradition and its unique conception of beauty in tangible materials and visible circumstances, I opted for the spiritual heritage, sensitivity, and tried to reflect these qualities in my work. Although partly consciously, this endeavor arises more from the subconscious legacy of my self. I sought to express this traditional sensitivity in the Japanese pavilion at Expo 92 in Seville. The main theme there was to express Japanese culture through architectural means, unifying customs and climate. The building of this exhibition was designated for dismantling after a short time. Therefore, I wanted to create architecture that, although it would soon cease to exist physically, would leave a lasting impression in the souls of all who encounter it, thus achieving eternity as an idea in their memory.

I decided to create a large wooden structure because it is capable of directly interpreting Japanese culture and aesthetic awareness to people from cultural areas characterized by stones and walls. This expressive medium was made possible through advanced techniques stemming from artificial intelligence. Japan is home to, as they say, the largest wooden structure, the Todai-ji temple in Nara. Yet the methods by which the building was constructed defy contemporary analysis and cannot be applied today. To realize my intent, advanced computer technology capable of analyzing complex structures in real-time was essential.(...)

The sensitivity from which shakkei arises, a method borrowed from landscape creation into gardening, where one attempts to "read" and give form to what is unique to a given habitat or place, represents a unique Japanese approach to nature. From these qualities, Japanese traditional culture of building truly evolves. I tried to understand and introduce into architecture not so much what is real and immediately apparent, but rather the abstraction and formless logic or idea that lies unseen behind it, the logic or idea that transforms its character to lend itself to a new context.(...)

I bring nature - light, wind, and water - into geometric and ordered architecture, thereby bringing it to life. In turn, as time flows, changes in weather transform the state of architecture. Contrasting elements clash with surprising results, and from these surprises, the expression of architecture is born, capable of moving the human soul and allowing us, in a brief moment, to glimpse eternity. The dwelling of eternity is thus in the one who perceives it.

As a visitor approaches the temple grounds, they cross the Isuzu River and adopt a solemn and serious mood as they walk along a gravel path through the dark forest to the entrance gate. The temple in Ise, shrouded in silence and exhibiting an impressive beauty of primeval simplicity, seems to be a fitting symbol of the aesthetics and lifestyle of ancient Japanese farmers.

The temple is completely rebuilt every twenty years in accordance with the practice of shikinen-sengu, a custom unlike any other in the world. This involves the regular dismantling of the temple in a settled cycle. This custom, which is believed to have originated during the Nara period (around 750), is still faithfully observed today. On the temple grounds, there are two alternative sites, and while one temple remains untouched, the other, exactly the same, is built beside it. After the sengu ceremony, when the embodiment of the deity is transferred, the old temple is dismantled. Shinto, a religion full of the beauty of ritual, finds its most beautiful expression here. Moreover, there is no surer way to pass down to future generations the method of construction based on ephemeral materials and labor techniques, such as thatched roofs and wooden posts directly set into the ground. Thus, because the temple is reborn every twenty years for over a millennium, the ancient method of architecture has been preserved virtually unchanged.

What is conveyed by the temple in Ise is not the physical substance of the building but the "style" and spiritual tradition itself. In it, we find sensitivity to beauty, simplicity, fresh vitality, and nobility in its most original and untainted expression - which is successfully passed down through generations of Japanese.

While Western thinking relies on individual consciousness, the Japanese traditionally embrace a pantheistic view of nature and leave consciousness to the god that resides in all things. In harmony with this, something spiritual and immaterial is concealed and resides within architectural forms, inherited from bygone times and continuously refined, changing its character. Moreover, since ancient times, the Japanese have tended to discover the eternal in that which withers and dies, feeling that the eternal is intuitively graspable - paradoxically - in that which has only a fleeting existence. The ideal metaphor is a flower, as it withers, losing its petals just when we realize it is at the height of its beauty. Although we might pray for such beauty to remain, nothing in this world is immortal, and ultimately, there is no more fitting symbol of our longing for eternity than that which immediately withers.

Rather than choosing the heritage of Japanese tradition and its unique conception of beauty in tangible materials and visible circumstances, I opted for the spiritual heritage, sensitivity, and tried to reflect these qualities in my work. Although partly consciously, this endeavor arises more from the subconscious legacy of my self. I sought to express this traditional sensitivity in the Japanese pavilion at Expo 92 in Seville. The main theme there was to express Japanese culture through architectural means, unifying customs and climate. The building of this exhibition was designated for dismantling after a short time. Therefore, I wanted to create architecture that, although it would soon cease to exist physically, would leave a lasting impression in the souls of all who encounter it, thus achieving eternity as an idea in their memory.

I decided to create a large wooden structure because it is capable of directly interpreting Japanese culture and aesthetic awareness to people from cultural areas characterized by stones and walls. This expressive medium was made possible through advanced techniques stemming from artificial intelligence. Japan is home to, as they say, the largest wooden structure, the Todai-ji temple in Nara. Yet the methods by which the building was constructed defy contemporary analysis and cannot be applied today. To realize my intent, advanced computer technology capable of analyzing complex structures in real-time was essential.(...)

The sensitivity from which shakkei arises, a method borrowed from landscape creation into gardening, where one attempts to "read" and give form to what is unique to a given habitat or place, represents a unique Japanese approach to nature. From these qualities, Japanese traditional culture of building truly evolves. I tried to understand and introduce into architecture not so much what is real and immediately apparent, but rather the abstraction and formless logic or idea that lies unseen behind it, the logic or idea that transforms its character to lend itself to a new context.(...)

I bring nature - light, wind, and water - into geometric and ordered architecture, thereby bringing it to life. In turn, as time flows, changes in weather transform the state of architecture. Contrasting elements clash with surprising results, and from these surprises, the expression of architecture is born, capable of moving the human soul and allowing us, in a brief moment, to glimpse eternity. The dwelling of eternity is thus in the one who perceives it.

Tadao Ando: The Eternal within the Moment

F. Dal Co: Tadao Ando: Complete Works, Phaidon, London 1995, p.474

Translation: Doc. PhDr. Lubomír Kostroň, M.A., CSc. / www.kostron.cz

Translation: Doc. PhDr. Lubomír Kostroň, M.A., CSc. / www.kostron.cz

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles

0

09.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Agony of Stuck Thoughts - The Trouble with Persistence

0

09.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: The Power of Unfulfilled Vision

0

09.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Interventions in Circumstances

4

03.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Materials, Geometry, and Nature

0

03.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: From the Water Chapel to the Chapel of Light