Tadao Ando: Agony of Stuck Thoughts - The Trouble with Persistence

Architecture differs from all other arts in its functionality. By its function, I do not mean how well or poorly one lives in a house. Rather, the question is whether a person has a place in the building. It does not matter if it is a truly realized work, a project, or merely a design where the architect sets their imagination free. Architecture without a relationship to people cannot exist. The program from which architecture grows and the interpretation of this program are essential to architecture.

When I engage with architecture, it is the same for me as when I think. However, this does not mean that I develop any particular logic in relation to the project. My nature is rather to try to unveil the essence of the matter. I always return to the starting point. Thinking, in my case, is a process that materializes in the form of drawings. The given program may wander through me along winding paths and undergo significant changes. I will not sacrifice the freedom of thought just to precisely meet certain requirements. The historical perspective of the project, understanding of nature, climate, ethnic traditions, comprehension of the time, and vision of the future, and certainly most of all the will to grasp all this in relation to the given problem—when any of these things are missing, it weakens the architectural work, and yet none of them should be evident in the final appearance of the work. I must absorb all this so that every stroke of the pencil expresses my will. I want all these things to sublimate into the space that I create.

Recently, thanks to projects in Venice, Basel, and Chicago, I had the opportunity to revisit buildings that have always had an inspiring and refreshing effect on me. In 1967, there were practically no skyscrapers in Japan, and the vertical structures of steel and glass in Chicago strangely fascinated me at that time. However, when I visited this city for the first time, I felt disappointment. The skyscrapers did not possess the strength or tension that I expected from modern architecture. The emphasis was placed solely on practicality and rationality, and there was beauty in them only as much as could fit under a fingernail. They were a celebration of the production of industrial society, and not a glimmer of the individuality of their creators was apparent. From nothing, you could glean what these people thought or felt.

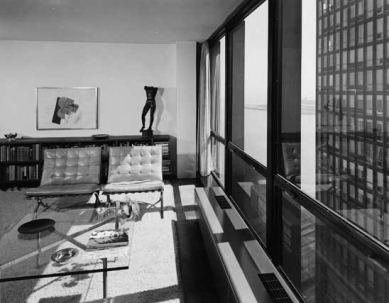

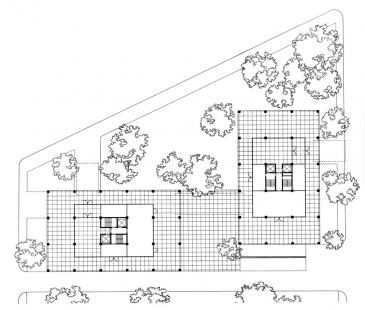

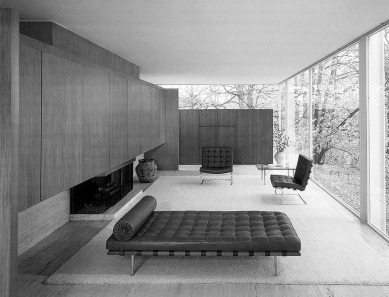

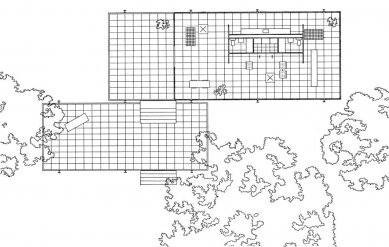

What made the journey not a complete loss were the apartments on Lake Shore Drive created by Mies van der Rohe. Although they were built of steel and glass like others in the vicinity, I could sense the imprint of the individual, Mies himself, within them. I also recognized him in the Farnsworth House. The appearance was perfect. Of course, the materials—steel, glass, prestressed concrete, and travertine on the floors—were skillfully combined to showcase their qualities, and the cleanly executed details were at the highest level available in the USA at that time. However, for anyone familiar with architecture, the amount of effort Mies expended to achieve his concept of space, despite (or rather precisely as a result of) the building's decorativeness, was frightening. A great deal of skill and effort was invested in the strict composition of geometry, intended as a means of creating a model of space.

In striving to achieve his ideal of architecture, Mies sought a degree of precision that seemed unattainable in architecture, and his efforts crystallized into aesthetics. This aesthetics, however, was so penetrating that it was horrifying—it concealed a certain kind of violence. It is hard to believe that this building could be intended for actual living. Strong design owes its existence to a great understanding of the client, but it is also the result of Mies van der Rohe's painful intellectual journey, during which he thoroughly contemplated the problems of steel and glass architecture and arrived at radical solutions.

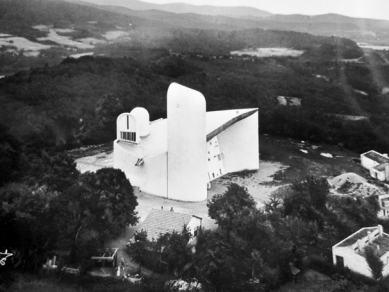

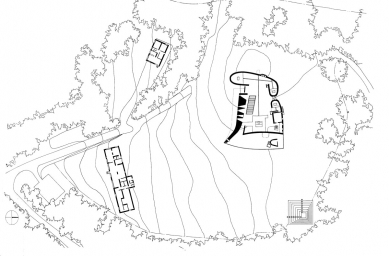

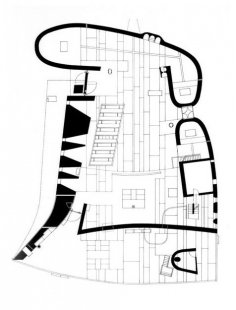

Another building I recently revisited is the Chapel of Ronchamp, although I have seen it many times since my first visit in 1965. This plastic structure, made of rough concrete, dates from the later years of Le Corbusier's life. Inside the chapel, the visitor is struck by ghostly lights entering through windows of various sizes, set with colored glass. This chapel, unlike Le Corbusier's early works, which were subordinate to reason and rational expression, seems to have been created directly and intuitively, almost presented as a painting. Its brutal physical strength does not diminish and permanently shocks.

How could Le Corbusier, always faithful to modern architecture, create such a building? One factor could be the accumulation of thoughts imposed upon him by the Second World War. Thinking was the only available thing for architects since nothing could be built. I believe he immersed himself into himself and reached such a deep level of understanding that he was ultimately able to transcend rationality and create this chapel with almost intuitive speed and energy.

The act of creation can be a source of joy and bring a sense of success, satisfaction, and pleasure; however, reaching this point requires going through an intellectual journey, where thoughts accumulate, full of torment. The work then arises from a delicate balance, where the torment is counterbalanced by the joy of liberating release. The thoughts of the creator, however, are often incompatible with the attributes of architecture—its economic, social, and functional character, as well as the ideas of the client or builder. Architecture as a form of expression can succeed when there is an effort on both sides to bridge these differences.

When I engage with architecture, it is the same for me as when I think. However, this does not mean that I develop any particular logic in relation to the project. My nature is rather to try to unveil the essence of the matter. I always return to the starting point. Thinking, in my case, is a process that materializes in the form of drawings. The given program may wander through me along winding paths and undergo significant changes. I will not sacrifice the freedom of thought just to precisely meet certain requirements. The historical perspective of the project, understanding of nature, climate, ethnic traditions, comprehension of the time, and vision of the future, and certainly most of all the will to grasp all this in relation to the given problem—when any of these things are missing, it weakens the architectural work, and yet none of them should be evident in the final appearance of the work. I must absorb all this so that every stroke of the pencil expresses my will. I want all these things to sublimate into the space that I create.

Recently, thanks to projects in Venice, Basel, and Chicago, I had the opportunity to revisit buildings that have always had an inspiring and refreshing effect on me. In 1967, there were practically no skyscrapers in Japan, and the vertical structures of steel and glass in Chicago strangely fascinated me at that time. However, when I visited this city for the first time, I felt disappointment. The skyscrapers did not possess the strength or tension that I expected from modern architecture. The emphasis was placed solely on practicality and rationality, and there was beauty in them only as much as could fit under a fingernail. They were a celebration of the production of industrial society, and not a glimmer of the individuality of their creators was apparent. From nothing, you could glean what these people thought or felt.

What made the journey not a complete loss were the apartments on Lake Shore Drive created by Mies van der Rohe. Although they were built of steel and glass like others in the vicinity, I could sense the imprint of the individual, Mies himself, within them. I also recognized him in the Farnsworth House. The appearance was perfect. Of course, the materials—steel, glass, prestressed concrete, and travertine on the floors—were skillfully combined to showcase their qualities, and the cleanly executed details were at the highest level available in the USA at that time. However, for anyone familiar with architecture, the amount of effort Mies expended to achieve his concept of space, despite (or rather precisely as a result of) the building's decorativeness, was frightening. A great deal of skill and effort was invested in the strict composition of geometry, intended as a means of creating a model of space.

In striving to achieve his ideal of architecture, Mies sought a degree of precision that seemed unattainable in architecture, and his efforts crystallized into aesthetics. This aesthetics, however, was so penetrating that it was horrifying—it concealed a certain kind of violence. It is hard to believe that this building could be intended for actual living. Strong design owes its existence to a great understanding of the client, but it is also the result of Mies van der Rohe's painful intellectual journey, during which he thoroughly contemplated the problems of steel and glass architecture and arrived at radical solutions.

Another building I recently revisited is the Chapel of Ronchamp, although I have seen it many times since my first visit in 1965. This plastic structure, made of rough concrete, dates from the later years of Le Corbusier's life. Inside the chapel, the visitor is struck by ghostly lights entering through windows of various sizes, set with colored glass. This chapel, unlike Le Corbusier's early works, which were subordinate to reason and rational expression, seems to have been created directly and intuitively, almost presented as a painting. Its brutal physical strength does not diminish and permanently shocks.

How could Le Corbusier, always faithful to modern architecture, create such a building? One factor could be the accumulation of thoughts imposed upon him by the Second World War. Thinking was the only available thing for architects since nothing could be built. I believe he immersed himself into himself and reached such a deep level of understanding that he was ultimately able to transcend rationality and create this chapel with almost intuitive speed and energy.

The act of creation can be a source of joy and bring a sense of success, satisfaction, and pleasure; however, reaching this point requires going through an intellectual journey, where thoughts accumulate, full of torment. The work then arises from a delicate balance, where the torment is counterbalanced by the joy of liberating release. The thoughts of the creator, however, are often incompatible with the attributes of architecture—its economic, social, and functional character, as well as the ideas of the client or builder. Architecture as a form of expression can succeed when there is an effort on both sides to bridge these differences.

Tadao Ando: The Agony of Sustained Thought: The Difficulty of Persevering

Source: GA Document 39, no.5 (May 1994)

Translation: Doc. PhDr. Lubomír Kostroň, M.A., CSc. / www.kostron.cz

Source: GA Document 39, no.5 (May 1994)

Translation: Doc. PhDr. Lubomír Kostroň, M.A., CSc. / www.kostron.cz

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles

0

20.05.2013 | Tadao Ando : Light

0

20.05.2013 | Tadao Ando: Representation and Abstraction

0

20.05.2013 | Tadao Ando: The Composition of Space and Nature

0

07.05.2013 | Tadao Ando: Face to Face with the Architecture Crisis

0

06.05.2013 | Tadao Ando: Body and Space

0

06.05.2013 | Tadao Ando: Mutual independence, mutual permeation

0

06.05.2013 | Tadao Ando: From modern architecture, enclosed within itself, to universality

0

09.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: The Power of Unfulfilled Vision

0

09.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Interventions in Circumstances

4

03.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Materials, Geometry, and Nature

0

03.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: From the Water Chapel to the Chapel of Light

0

03.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Eternity in a Moment