Tadao Ando: Materials, Geometry, and Nature

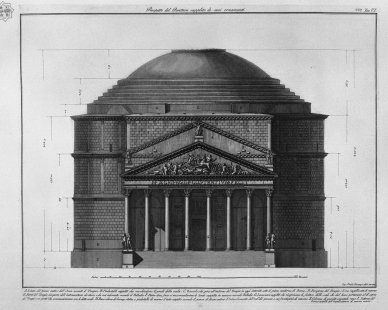

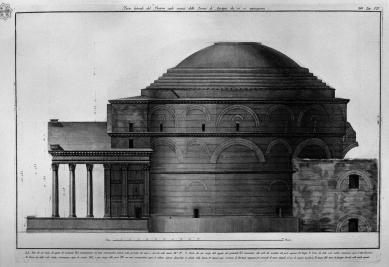

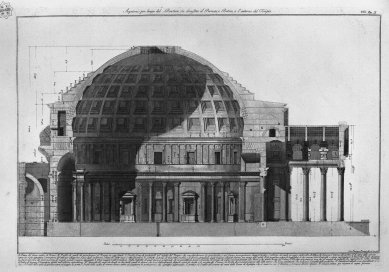

For the first time, I had an experience of space in the architecture of the Roman Pantheon. It is often said that Roman architecture has a character defined more by space than Greek architecture. However, what I felt was not space in the conceptual sense of the word. It was truly an illuminated space. As is well known, the Pantheon consists of a hemispherical dome with a diameter of 43.2 meters, placed on a hollow cylindrical base of the same diameter. The height of the structure is also 43.2 meters, so it can be said that the entire structure encompasses the volume of a gigantic sphere. The fact that the entire structure is illuminated by some kind of "eye" with a diameter of 9 meters, located at the top of the dome, truly makes the whole space visible. Such a synergy of mass and light cannot be experienced in nature. It is only possible through architecture. It is precisely the power of architecture to create such a vision that deeply moved me.

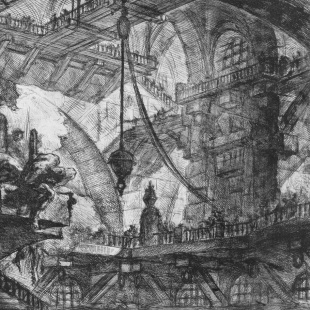

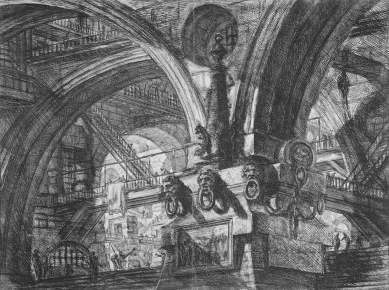

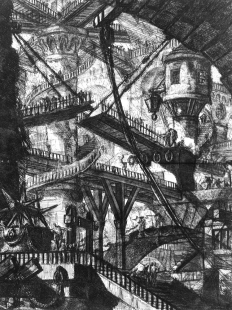

In my good memory, there is another space, coming from the West. The space of Piranesi's imaginary structures, contained in the maps of the Roman Empire and the famous engravings of imaginary prisons, in which he had to express his own sense of alienation from reality. Particularly striking were his interiors of prisons, due to a certain quality that has been generally labeled as Piranesian. Space in traditional Japanese architecture unfolds horizontally. However, in the three-dimensional mazes of Piranesi's prisons, verticality dominates—the ascending staircases of spiritual movement.

The geometric order of the Pantheon and the verticality of Piranesi's space wonderfully contrast with traditional Japanese architecture. Japanese architecture is distinctly horizontal and non-geometric, and its characteristics are irregular spaces. In a certain sense, the architect is formless (without shape). Architecture is connected to nature, and space flows freely. Because both the Pantheon and Piranesi's interiors are in complete opposition to Japanese architecture, they represent for me a space according to Western architecture. It seems to me that the goal of my work has long been to integrate both of these contrasting concepts of space.

I am convinced that three elements are essential for the crystallization of architecture. The first is authentic materials, i.e., materials whose essence is stripped bare—such as concrete or unpainted wood. The second is pure geometry, as in the case of the Pantheon. This is the basis or framework that lends being and presence to architecture. It can be volumes like in the case of Platonic solids or three-dimensional frames (structures, frames), because I think that the latter are a purer geometry. The last element is nature. I do not mean nature in its raw state, but domesticated nature—nature that man has impressed order upon, and which contrasts with chaotic nature. Perhaps it can be better termed as order abstracted from nature: light, sky, and water, from which we have created abstractions. When we apply such nature in architecture, which consists, as I have already said, of materials and geometry, then architecture itself becomes by its nature an abstraction. Architecture is strong and radiates only through the combination of these three elements. Man is then moved by a vision, which is possible—like in the case of the Pantheon—only thanks to architecture.

In my good memory, there is another space, coming from the West. The space of Piranesi's imaginary structures, contained in the maps of the Roman Empire and the famous engravings of imaginary prisons, in which he had to express his own sense of alienation from reality. Particularly striking were his interiors of prisons, due to a certain quality that has been generally labeled as Piranesian. Space in traditional Japanese architecture unfolds horizontally. However, in the three-dimensional mazes of Piranesi's prisons, verticality dominates—the ascending staircases of spiritual movement.

The geometric order of the Pantheon and the verticality of Piranesi's space wonderfully contrast with traditional Japanese architecture. Japanese architecture is distinctly horizontal and non-geometric, and its characteristics are irregular spaces. In a certain sense, the architect is formless (without shape). Architecture is connected to nature, and space flows freely. Because both the Pantheon and Piranesi's interiors are in complete opposition to Japanese architecture, they represent for me a space according to Western architecture. It seems to me that the goal of my work has long been to integrate both of these contrasting concepts of space.

I am convinced that three elements are essential for the crystallization of architecture. The first is authentic materials, i.e., materials whose essence is stripped bare—such as concrete or unpainted wood. The second is pure geometry, as in the case of the Pantheon. This is the basis or framework that lends being and presence to architecture. It can be volumes like in the case of Platonic solids or three-dimensional frames (structures, frames), because I think that the latter are a purer geometry. The last element is nature. I do not mean nature in its raw state, but domesticated nature—nature that man has impressed order upon, and which contrasts with chaotic nature. Perhaps it can be better termed as order abstracted from nature: light, sky, and water, from which we have created abstractions. When we apply such nature in architecture, which consists, as I have already said, of materials and geometry, then architecture itself becomes by its nature an abstraction. Architecture is strong and radiates only through the combination of these three elements. Man is then moved by a vision, which is possible—like in the case of the Pantheon—only thanks to architecture.

Tadao Ando: Materials, Geometry and Nature

Source: T.Ando, W.Blaser: Sketches, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel 1990

Source: T.Ando, W.Blaser: Sketches, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel 1990

Translation: Doc. PhDr. Lubomír Kostroň, M.A., CSc. / www.kostron.cz

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

4 comments

add comment

Subject

Author

Date

Díky

Jaroslav Matoušek

03.03.13 07:56

Další překlady budou následovat...

Petr Šmídek

03.03.13 10:25

další překlady

martin daněk

04.03.13 03:54

Taky díky!

Tomas Zdvihal

04.03.13 09:18

show all comments

Related articles

0

07.05.2013 | Tadao Ando: Face to Face with the Architecture Crisis

0

06.05.2013 | Tadao Ando: From modern architecture, enclosed within itself, to universality

0

09.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Agony of Stuck Thoughts - The Trouble with Persistence

0

09.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: The Power of Unfulfilled Vision

0

09.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Interventions in Circumstances

0

03.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: From the Water Chapel to the Chapel of Light

0

03.03.2013 | Tadao Ando: Eternity in a Moment