The last student of Gočár has departed

Acad. Arch. Jaroslav KOSEK (March 12, 1907 Vamberk – April 30, 2006 Prague)

With the death of architect Jaroslav Kosek, the dean of the Czech architectural community, the era illuminated by the exceptional presence of Josef Gočár has definitively ended. His direct, fair demeanor and double-breasted attire clearly reflected the elegant style of his teacher. He spent, as he said, the 5 happiest years of his life 1935-1939 (3 years of study, an honorary year, and a year of employment in Gočár's office).

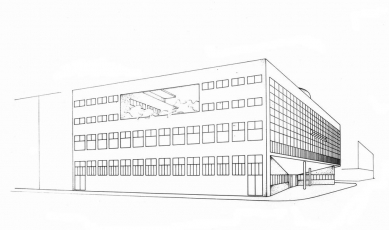

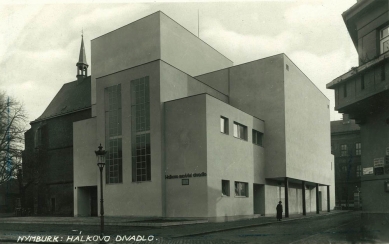

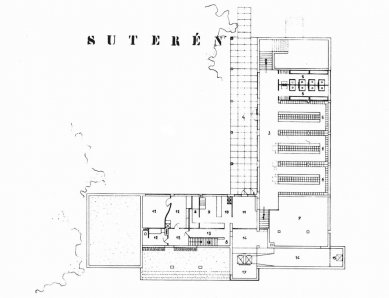

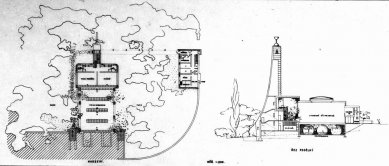

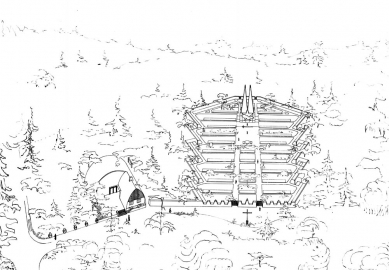

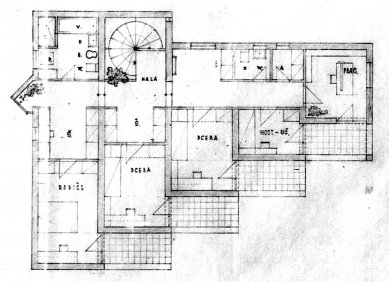

He gained a reputation as a creative architect through residential buildings in Nymburk, Poděbrady, Podbrezová, and Slatinské Doly in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, the realization of Hálkovo Theatre in Nymburk (1933-36), and remarkable competition designs for the town hall in Rychnov (1940), Lidice (1945), the Dukla Memorial, and the Old Town Hall (both 1946).

During the communist era, in the time of socialist realism, he withdrew from the studio of the national artist Jiří Kroha at the Prague Stavoprojekt to the field of industrial construction and worked on heavy industrial buildings in Rudný project (later Interprojekt) for 25 years until his retirement in 1977.

On the occasion of his 80th birthday, at the beginning of 1989 he provided me with a long interview, parts of which were published in the magazines Umění a řemesla and Československý architekt. From this interview, I selected the most interesting passages for archiweb.

Vladimír Šlapeta: How did you get to AVU with Prof. Josef Gočár?

Jaroslav Kosek: According to the then regulations, after graduating from the municipal school in my hometown Vamberk, I had to have two years of construction practice. Only then could I continue my studies at the Higher Industrial School of Construction in Hradec Králové, which I completed in 1930. A prerequisite for continuing my studies at the school with Prof. J. Gočár was at least three years of practical experience in the field and the submission of independent architectural works. I met this condition. I worked for builders J. Duchoslav in Česká Třebová (in 1930-1931) and L. Caňkář in Nymburk (1932-1934). Several buildings were realized in Česká Třebová and Nymburk according to my independent designs, and besides that, I achieved several successes in public competitions. Among them, I particularly value my victory in the competition for Hálkovo Theatre in Nymburk. The commissioning of this building had a decisive influence on my acceptance to the Academy with Prof. Gočár.

How would you characterize the personality of your teacher?

I first met him in 1924 during my practice at the Hořeňovský company in Pardubice when he came to supervise the installation of the inscriptions on the Anglobanka building. He was the first person who left an impression of greatness on me. In my life, I have not met a second personality so distinctly prominent. Even then, I developed a desire to attend his school. "Our lord" - this honorary title was inherited from Jan Kotěra, and after Josef Gočár, it was also for Jaroslav Fragner - was a man of polished behavior and appearance: tall stature, neatly combed, with a captivating and intelligent gaze. He smoked cigars and walked - like an elegant man - with a cane, but always upright. He was not arrogant and did not show his superiority over his students. Nonetheless, schoolwork carried out without a creative spirit, merely technically, could lead to "dismissal." In school designs, he allowed complete freedom and demanded independence. His behavior earned him natural respect, dignity, and reverence from all his students and friends. He often visited the Mánes café. On Sunday mornings, he would go to Slavia, where the head waiter would shower him with all the domestic and foreign magazines.

On the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday - like all previous ones - on March 13, 1945, I congratulated him. Professor kindly thanked me and perhaps sent the last architectural sketch to his student, who - as he said - "was to be his successor." Sadness came when he passed away on September 10, 1945. He is buried at Slavín, and there I can occasionally complain about how our architecture and our cities have turned out.

And what about the atmosphere of the school and Gočár's studio?

The classrooms of students from all three years on the ground floor were interconnected, creating an atmosphere of joyful work, full of free debates. However, J. Gočár did not appreciate political themes. He came to the studio in the morning and afternoon outside the theory lectures. Often, out of the blue, he would present a compositional exercise on the subject of small architecture such as a sales stand, a gas station, a memorial, etc. I remember once he came to me when we were working on a water tower and said, "So show me!" I replied that I already had it in my head. "So they have a 'plavajz' here, and draw it on the table!" he reacted then. The idea was there, so I drew it and received a grade of "excellent," accompanied by a smile.

With "Our lord," I was employed in the studio, which was on the first floor, during my three years of study as well as during the "honorary year" of 1937 to 1938. By then, I was already operating in my own office - in the room to the right of the entrance to the school building and was also working on my own commissions, such as execution projects for the Czech colony in Slatinské Doly in Subcarpathian Ruthenia and residential buildings in Podbrezová, which were built before the war.

The head of Gočár's studio was the robust and very hardworking architect Josef Mach, who lit one cigarette from another. Every morning before "Our lord" arrived, we sang together as his "slaves" "The Orphaned Child" and "I wandered through Trenčín on foot," and then we quietly "worked." During the period when the second project for the modern gallery at Letná was being developed, it was cheerier with two more collaborators - architect and painter Alois Wachsmann and sculptor Vincenc Makovský. A. Wachsmann constantly let out fragrant smoke from his pipe and V. Makovský slowly took half-liter beers one after another from under the table...

The snacks for the workers were brought by the caretaker - janitor Horák, and everyone except one gave him 1 Kč as "diškreci." That "one" only paid 20 haléřů, and so when Mr. Horák was in a bad mood, he would say he wouldn't bring him a snack, and he didn't. Otherwise, Mr. Horák, whom we called "daddy," was fatherly kind, just like his wife "mom." They were inseparably part of the school, creating its atmosphere. They cared for all students as if they were their own children. When someone had a cold, "mom" would bring them tea with lemon. Mr. Horák, who was originally a carpenter, was brought from Vienna by Prof. Jan Kotěra; he remained at the school until the end of the First Republic. During the First World War, the Horáks lost their only son - a sculptor, which they bore very heavily, and perhaps the students sensed this, and that's why they addressed them as "daddy" and "mom." At the annual exhibitions of students' works, "daddy" was dressed in a tailcoat and "mom" in black. This is how they received visitors - actors, ministers, and Mr. President.

On the day we submitted our annual state exam projects, which we had to manage in five weeks and which were judged by a commission consisting of - Prof. J. Gočár, Kamil Roškot for the Association of Academic Architects, and Josef Zasche for the Association of German Architects, representatives from the Ministry of Education and National Enlightenment, and other professors of AVU, it was an unwritten protocol that we - the students - "corporately" headed to the restaurant in Stromovka. After about two to three hours, we traditionally returned along the direct path we had worn down, and finally over the fence back to the Academy, while the esteemed commission watched our athletic performances with interest and smiles from the windows...

What would you wish for today's young architects?

I would wish for the future ones to be able to study with complete freedom and with enlightened professors who would truly be creative personalities. To experience what we did during our studies with the unforgettable Josef Gočár. And for young architects, I would wish them to be able to create freely and for no one to dictate to them how architecture should or must be done. They could realize urbanism and architecture that reflects the contemporary development of life and does not only depict spiritual poverty and material backwardness. I wish them an architecture that is not just a contemporary "ton" production, does not age, and resonates in harmony with history, creating hope and perspectives for both present and future life.

He gained a reputation as a creative architect through residential buildings in Nymburk, Poděbrady, Podbrezová, and Slatinské Doly in Subcarpathian Ruthenia, the realization of Hálkovo Theatre in Nymburk (1933-36), and remarkable competition designs for the town hall in Rychnov (1940), Lidice (1945), the Dukla Memorial, and the Old Town Hall (both 1946).

During the communist era, in the time of socialist realism, he withdrew from the studio of the national artist Jiří Kroha at the Prague Stavoprojekt to the field of industrial construction and worked on heavy industrial buildings in Rudný project (later Interprojekt) for 25 years until his retirement in 1977.

On the occasion of his 80th birthday, at the beginning of 1989 he provided me with a long interview, parts of which were published in the magazines Umění a řemesla and Československý architekt. From this interview, I selected the most interesting passages for archiweb.

Vladimír Šlapeta

Vladimír Šlapeta: How did you get to AVU with Prof. Josef Gočár?

Jaroslav Kosek: According to the then regulations, after graduating from the municipal school in my hometown Vamberk, I had to have two years of construction practice. Only then could I continue my studies at the Higher Industrial School of Construction in Hradec Králové, which I completed in 1930. A prerequisite for continuing my studies at the school with Prof. J. Gočár was at least three years of practical experience in the field and the submission of independent architectural works. I met this condition. I worked for builders J. Duchoslav in Česká Třebová (in 1930-1931) and L. Caňkář in Nymburk (1932-1934). Several buildings were realized in Česká Třebová and Nymburk according to my independent designs, and besides that, I achieved several successes in public competitions. Among them, I particularly value my victory in the competition for Hálkovo Theatre in Nymburk. The commissioning of this building had a decisive influence on my acceptance to the Academy with Prof. Gočár.

How would you characterize the personality of your teacher?

I first met him in 1924 during my practice at the Hořeňovský company in Pardubice when he came to supervise the installation of the inscriptions on the Anglobanka building. He was the first person who left an impression of greatness on me. In my life, I have not met a second personality so distinctly prominent. Even then, I developed a desire to attend his school. "Our lord" - this honorary title was inherited from Jan Kotěra, and after Josef Gočár, it was also for Jaroslav Fragner - was a man of polished behavior and appearance: tall stature, neatly combed, with a captivating and intelligent gaze. He smoked cigars and walked - like an elegant man - with a cane, but always upright. He was not arrogant and did not show his superiority over his students. Nonetheless, schoolwork carried out without a creative spirit, merely technically, could lead to "dismissal." In school designs, he allowed complete freedom and demanded independence. His behavior earned him natural respect, dignity, and reverence from all his students and friends. He often visited the Mánes café. On Sunday mornings, he would go to Slavia, where the head waiter would shower him with all the domestic and foreign magazines.

On the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday - like all previous ones - on March 13, 1945, I congratulated him. Professor kindly thanked me and perhaps sent the last architectural sketch to his student, who - as he said - "was to be his successor." Sadness came when he passed away on September 10, 1945. He is buried at Slavín, and there I can occasionally complain about how our architecture and our cities have turned out.

And what about the atmosphere of the school and Gočár's studio?

The classrooms of students from all three years on the ground floor were interconnected, creating an atmosphere of joyful work, full of free debates. However, J. Gočár did not appreciate political themes. He came to the studio in the morning and afternoon outside the theory lectures. Often, out of the blue, he would present a compositional exercise on the subject of small architecture such as a sales stand, a gas station, a memorial, etc. I remember once he came to me when we were working on a water tower and said, "So show me!" I replied that I already had it in my head. "So they have a 'plavajz' here, and draw it on the table!" he reacted then. The idea was there, so I drew it and received a grade of "excellent," accompanied by a smile.

With "Our lord," I was employed in the studio, which was on the first floor, during my three years of study as well as during the "honorary year" of 1937 to 1938. By then, I was already operating in my own office - in the room to the right of the entrance to the school building and was also working on my own commissions, such as execution projects for the Czech colony in Slatinské Doly in Subcarpathian Ruthenia and residential buildings in Podbrezová, which were built before the war.

The head of Gočár's studio was the robust and very hardworking architect Josef Mach, who lit one cigarette from another. Every morning before "Our lord" arrived, we sang together as his "slaves" "The Orphaned Child" and "I wandered through Trenčín on foot," and then we quietly "worked." During the period when the second project for the modern gallery at Letná was being developed, it was cheerier with two more collaborators - architect and painter Alois Wachsmann and sculptor Vincenc Makovský. A. Wachsmann constantly let out fragrant smoke from his pipe and V. Makovský slowly took half-liter beers one after another from under the table...

The snacks for the workers were brought by the caretaker - janitor Horák, and everyone except one gave him 1 Kč as "diškreci." That "one" only paid 20 haléřů, and so when Mr. Horák was in a bad mood, he would say he wouldn't bring him a snack, and he didn't. Otherwise, Mr. Horák, whom we called "daddy," was fatherly kind, just like his wife "mom." They were inseparably part of the school, creating its atmosphere. They cared for all students as if they were their own children. When someone had a cold, "mom" would bring them tea with lemon. Mr. Horák, who was originally a carpenter, was brought from Vienna by Prof. Jan Kotěra; he remained at the school until the end of the First Republic. During the First World War, the Horáks lost their only son - a sculptor, which they bore very heavily, and perhaps the students sensed this, and that's why they addressed them as "daddy" and "mom." At the annual exhibitions of students' works, "daddy" was dressed in a tailcoat and "mom" in black. This is how they received visitors - actors, ministers, and Mr. President.

On the day we submitted our annual state exam projects, which we had to manage in five weeks and which were judged by a commission consisting of - Prof. J. Gočár, Kamil Roškot for the Association of Academic Architects, and Josef Zasche for the Association of German Architects, representatives from the Ministry of Education and National Enlightenment, and other professors of AVU, it was an unwritten protocol that we - the students - "corporately" headed to the restaurant in Stromovka. After about two to three hours, we traditionally returned along the direct path we had worn down, and finally over the fence back to the Academy, while the esteemed commission watched our athletic performances with interest and smiles from the windows...

What would you wish for today's young architects?

I would wish for the future ones to be able to study with complete freedom and with enlightened professors who would truly be creative personalities. To experience what we did during our studies with the unforgettable Josef Gočár. And for young architects, I would wish them to be able to create freely and for no one to dictate to them how architecture should or must be done. They could realize urbanism and architecture that reflects the contemporary development of life and does not only depict spiritual poverty and material backwardness. I wish them an architecture that is not just a contemporary "ton" production, does not age, and resonates in harmony with history, creating hope and perspectives for both present and future life.

The English translation is powered by AI tool. Switch to Czech to view the original text source.

0 comments

add comment

Related articles

0

05.03.2023 | Jaroslav Kosek Architect 1909-2006 - presentation of the book at the ŠA AVU

0

14.08.2020 | Café Re:public = a different perspective on Petřín

0

29.06.2020 | When the architect's ideas meet the client's

0

08.06.2020 | The house that opens up to its owners and nature at a touch

0

28.05.2020 | <brick house bent like a bow

0

22.04.2020 | Schüco supports the KARMIN project: Architecture aims to assist in preventing the spread of infection in hospitals

0

02.04.2020 | The Mediterranean villa opened along its entire length to infinite views

0

19.02.2020 | Schüco DCS SmartTouch: Open the door for visitors using your mobile, you don’t need to be at home

0

15.01.2020 | Oasis of freedom and pure relaxation without work all year round

0

16.12.2019 | The company Schüco has released its second sustainability report

0

02.12.2019 | Sliding facade that respects the mood of the residents

0

01.11.2019 | The company Schüco was the first certified for the responsible use of aluminum

1

14.10.2019 | Villa Melstokke, Karmøy Island

0

30.07.2019 | Private house in German Gersthofen in the style of Mies van der Rohe

1

08.04.2019 | Renovation of a family house in the German city of Bergisch Gladbach